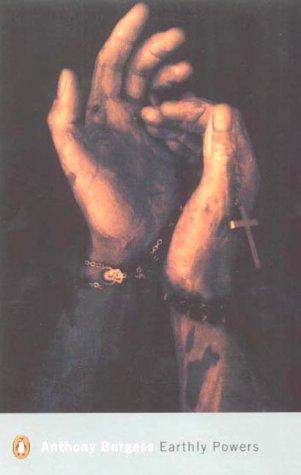

Anthony Burgess - Earthly Powers

Here you can read online Anthony Burgess - Earthly Powers full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1993, publisher: Carroll & Graf, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Earthly Powers

- Author:

- Publisher:Carroll & Graf

- Genre:

- Year:1993

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earthly Powers: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Earthly Powers" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Earthly Powers — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Earthly Powers" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Earthly Powers

Anthony Burgess

First published in 1980

TO LIANA

CHAPTER 1

It was the afternoon of my eighty-first birthday, and I was in bed with my catamite when Ali announced that the archbishop had come to see me.

"Very good, Ali," I quavered in Spanish through the closed door of the master bedroom. "Take him into the bar. Give him a drink."

"Hay dos. Su capelln tambin."

"Very good, Ali. Give his chaplain a drink also."

I retired twelve years ago from the profession of novelist. Nevertheless you will be constrained to consider, if you know my work at all and take the trouble now to reread that first sentence, that I have lost none of my old cunning in the contrivance of what is known as an arresting opening. But there is really nothing of contrivance about it. Actuality sometimes plays into the hands of art. That I was eighty-one I could hardly doubt: congratulatory cables had been rubbing it in all through the forenoon. Geoffrey, who was already pulling on his overtight summer slacks, was, I supposed, my Ganymede or male lover as well as my secretary. The Spanish word 'arzobispo' certainly means archbishop. The time was something after four o'clock on a Maltese June daythe twenty-third, to be exactand to spare the truly interested the trouble of consulting Who's Who.

Geoffrey sweated too much and was running to fat (why does one say running? Geoffrey never ran). The living, I supposed, was too easy for a boy of thirty-five. Well, the time for our separation could not, in the nature of things, be much longer delayed. Geoffrey would not be pleased when he attended the reading of my will. "The old bitch, my dear, and all I did for him." I would do for him too, though posthumously, posthumously.

I lay a little while, naked, mottled, sallow, emaciated, smoking a cigarette that should have been postcoital but was not. Geoffrey put on his sandals puffing, creasing his stomach into three bunches of fat, and then his flowery coatshirt. Finally he hid himself behind his sunglasses, which were of the insolent kind whose convexities flash metallic mirrors at the world. I observed my eighty-one-year-old face and neck quite clearly in them: the famous ancient grimness of one who had experienced life very keenly, the unfleshed tendons like cables, the anatomy of the jaws, the Fribourg and Treyer cigarette in its Dunhill holder relating me to an era when smoking had been an act to be performed with elegance. I looked without rancour on the double image while Geoffrey said: "I wonder what his archbishship is after. Perhaps he's delivering a bull of excommunication. In a gaudy gift wrapper, of course."

"Sixty years too late," I said. I handed Geoffrey the half-smoked cigarette to stub out in one of the onyx ashtrays, and I noticed how he begrudged even that small service. I got out of bed, naked, mottled, sallow, emaciated. My summer slacks were, following nominal propriety, far from tight. The shirt of begonias and orchids was ridiculous on a man of my age, but I had long drawn the fang of Geoffrey's sneers by saying: "Dear boy, I must habituate myself to the prospect of reverential infloration." That phrase dated back to 1915. I had heard it in Lamb House, Rye, but it was less echt Henry James than Henry James mocking echt Meredith. He was remembering 1909 and some lady's sending Meredith too many flowers. "Reverential infloration, ho ho ho," James had mocked, rolling in mock mirth.

"The felicitations of the faithful, then."

I did not care at all for the aspirated stress Geoffrey laid on the word. It connoted sex and his own shameless infidelities; it was a word I had once used to him weeping; it carried for me a traditional moral seriousness that was no more than a camp joke to Geoffrey's generation.

"The faithful," I aspirated back, "are not supposed to read my books. Not here, on Saint Paul's holy island. Here I am immoral and anarchic and agnostic and rational. I think I can guess what the archbishop wants. And he wants it precisely because I am all of those things."

"Clever old devil, aren't you?" His mirrors caught golden stone from the Triq al-Kbira, meaning Street the Big or Main Street, outside the open casement.

I said, "There is much neglected correspondence down below in what you call your office. Sickened by your sloth, I took it upon myself to open a letter or two, hot from the hands of the mailman. One of them bore a Vatican stamp."

"Ah, fuck you," Geoffrey smiled, or seemed to: I could not of course see his eyes. Then he mocked my slight lisp: "Thickened by your thloth." Then he said "Fuck you" again, this time sulkily.

"I think," I said, hearing the senile dry wavering and hating it, "I'd better sleep alone in future. It would be seemly at my age."

"Facing facts at last, dear?"

"Why"I trembled at the big blue wall mirror, brushing back my scant strands"do you make things sound mean and dirty? Warmth. Comfort. Love. Are those dirty words? Love, love. Is that dirty?"

"Matters of the heart," Geoffrey said, seeming to smile again. "We must watch that rather mature pump, must we not? Very well. Each of us sleeps in his sundered bed. And if you cry out in the night, who will hear you?"

Wer, wenn ich schrie... Who had said or written that? Of course, poor great dead Rilke. He had cried in my presence in a low beershop in Trieste, not far from the Aquarium. The tears had flowed mostly from his nose, and he had wiped his nose on his sleeve. "You have always managed to sleep soundly enough at my labouring side," I said. "Soundly enough not to be sensible even of the sharp prodding of my finger." And then, quavering shamefully: "Faithful, faithful." I was ready to weep again, the word was so loaded. I remembered poor Winston Churchill, who, at about my present age, would weep at words like greatness. It was called emotional lability, a disease of the senile.

Geoffrey did not mouth a smile now, nor set his jaw in weak truculence. The lower part of his face showed a sort of compassion, the upper the twin and broken me. Poor old bugger, he would be saying to himself and, later perhaps, to some friend or toady in the bar of the Corinthia Palace Hotel, poor senile decrepit lonely old impotent sod. To me, with kind briskness: "Come, dear. Your fly is properly fastened? Good."

"It would not show. Not inflorated as I am."

"Splendid. Let us then put on the mask of distinguished immoral author. His archbishship awaits." And he opened the heavy door which led straight into the airy upper salon. At my age I could, can, take any fierce amount of light and heat, and both these properties of the South roared in, like a Rossini finale in stereophony, from the open and unshuttered casements. To the right were the housetops and gaudy washing of Lija, a passing bus, quarrelling children; to the left, beyond crystal and statuary and the upper terrace, the hiss and pump hum came up of the irrigation of my orange and lemon trees. In other words, I heard life going on, and it was a comfort. We trod cool marble, heavy white bear fur, marble, fur, marble. Over there was the William Foster harpsichord, which I had bought for my former friend and secretary, Ralph, faithless, some of its middle strings broken one night in a drunken tantrum by Geoffrey. On the walls were paintings by my great contemporaries: now fabulously valuable but all acquired cheap when, though still young, I had emerged from struggle. There were cases showing off jade, ivory, glass, metal bibelots or objets d'art. How the French terms, admitting their triviality, somehow cleansed them of it. The tangible fruits of success. The real fight, the struggle with form and expression, unwon.

Oh, my Godthe real fight? I was thinking like an author, not like a human, though senile, being. As though conquering language mattered. As if, at the end of it all, there were anything more important than clichs. Faithful. You have failed to be faithful. You have lapsed, or fallen, into infidelity. I believe that a man should be faithful to his beliefs. O come all ye faithful. That could still evoke tearful nostalgia at Christmas. The reproduction in my father's surgery of that anecdotal horrorno, who was I to say it was a horror?: the wide-eyed soldier at his post while Pompeii fell. Faithful unto death. The felicitations of the faithful, then. The world of the homosexual has a complex language, brittle yet sometimes excruciatingly precise, fashioned out of the clichs of the other world. So, cher maitre, these are the tangible fruits of your success.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Earthly Powers»

Look at similar books to Earthly Powers. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Earthly Powers and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.