F IRSTLY, I would like to elaborate here on the debts of gratitude I owe to my dedicatees and others. To my wife Linda/Amoghavajri Leigh who has shown great patience over the years with my preoccupations, and she has been an unfailing help with the computer. To Ron Pickersgill who gave me my first book on Lawrence when I was fourteen. To my friend Graham Chainey, a Lawrence scholar with a deep knowledge of the subject, and a copious memory. Also to Anthony Lines for support and help in the fraught early days of writing and also in the search for a publisher.

Secondly, I would like to register my debt to the many scholars and translators whose books I have read with interest and profit. Their books feature in the bibliography: and without their expertise on Chivalry, Classical Greek Stoicism and Cynicism in particular, and Ancient philosophy in general, I would not have been able to write this book.

Thirdly, I register here my gratitude to my editor, Robert Forsyth of Chevron Publishing and Tattered Flag Press. His careful editing has greatly improved my original manuscript. He is the only publisher with the bottle to publish this book, which is sui generis.

Finally, any errors of fact or interpretation are entirely mine.

Why Lawrence

Another book on Lawrence? Who was he anyway?

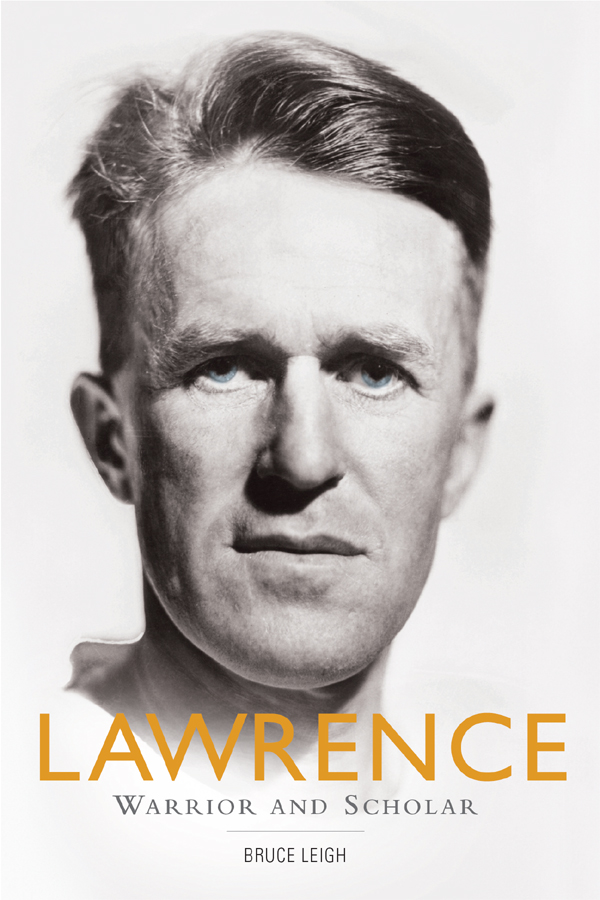

M OST people have either seen the film of his exploits in Arabia, or come across, if not read, one of the many books about him. Even so, there is something elusive about this small but charismatic fellow. In one sense he is an intellectual Victorian born in 1888who seems to mutate into many different figures as he enters the 20th Century only to die suddenly in a motorcycle crash in 1935. His wandering parents finally settle in Oxford, where he and his four brothers all illegitimate proceed successfully through the classical and Christian education, which the city had offered for so long. He shows from the earliest days an unusual character, combining practical skills, a strong antiquarian bent and an interest in archaeology, with a cult of self-hardening; an urge to explore the limits of the physical and mental self beyond the complacencies of his class and time. His later fame, resting on his extraordinary achievements in helping to foment and lead the revolt of the nomadic and feuding Arabs in the First World War, is only one facet of his life. Equally, he could live on as a brilliant letter-writer, a diplomat, archaeologist, historian, or as a practitioner and theorist of guerrilla warfare, and developer of speedboats for the RAF. Critics still argue about the merits and demerits of his account of the Arab Revolt, the Seven Pillars of Wisdom and his book about the beginnings of the RAF, The Mint, written from the inside as a nobody with another name. Whatever may be the case, along with the letters, they will ensure his place in English writing.

The general account of his life has been rehearsed by many authors. In a broad sense the writing about him may be divided between two main types: the historical overviews (for or against), and the anoraksthe latter perhaps more interested in photographing the factory which made the spark plugs for his motorcycles. Although they are both useful, they are not what interest me. In my view, Lawrence is nothing if he is not a Mind. Accordingly, I go in search of this Mind, trying to understand and to begin to delineate it via his formation and experience. It is because he mixed with all classes, and certainly knew the powerful and influential people of his time, that I begin with his judgement of Ronald Storrs, who was military Governor of Jerusalem and Oriental Secretary in Cairo. Storrs was of a similar intellectual calibre and formation; therefore, I believe their mutual appraisal is instructive.

Finally, I do believe that there is something to be learnt from Lawrences life and writings, and that there is a message in them which our times need, even though we are very unlikely to hear it or believe it. By trying to delineate his mind and personality, my hope is that some, however few, will hear this message and even transmit it to the future.

His shadow would have covered our work and British policy in the East like a cloak, had he been able to deny himself the world, and to prepare his mind and body with the sternness of an athlete for a great fight.

Seven Pillars of Wisdom, , 1922 Oxford Text.

As a youth of 14, interested in Lawrence, I was given a Penguin book, edited by David Garnett, called The Essential T.E. Lawrence. One passage, in which Garnett quotes Eric Kennington, has stayed with me ever since:

I had long wished to get a statement from him, which would throw light on the spiritual difference I knew there was between us. What was his God? He answered without hesitation, and once more I missed his words, so beautiful was his face. He had a glory and a light shone in his eyes, but more of sunset, than sunrise or midday. What I think I heard in the flow of eloquence, was a record of process without aim or end, creation followed by dissolution, rebirth, and then decay to wonder at and to love. But not a hint of a god and certainly none of the Christian God