CAMPAIGN 221

THE FIRST BATTLE OF THE MARNE 1914

The French miracle halts the Germans

| IAN SUMNER | ILLUSTRATED BY GRAHAM TURNER |

Series editor Marcus Cowper

CONTENTS

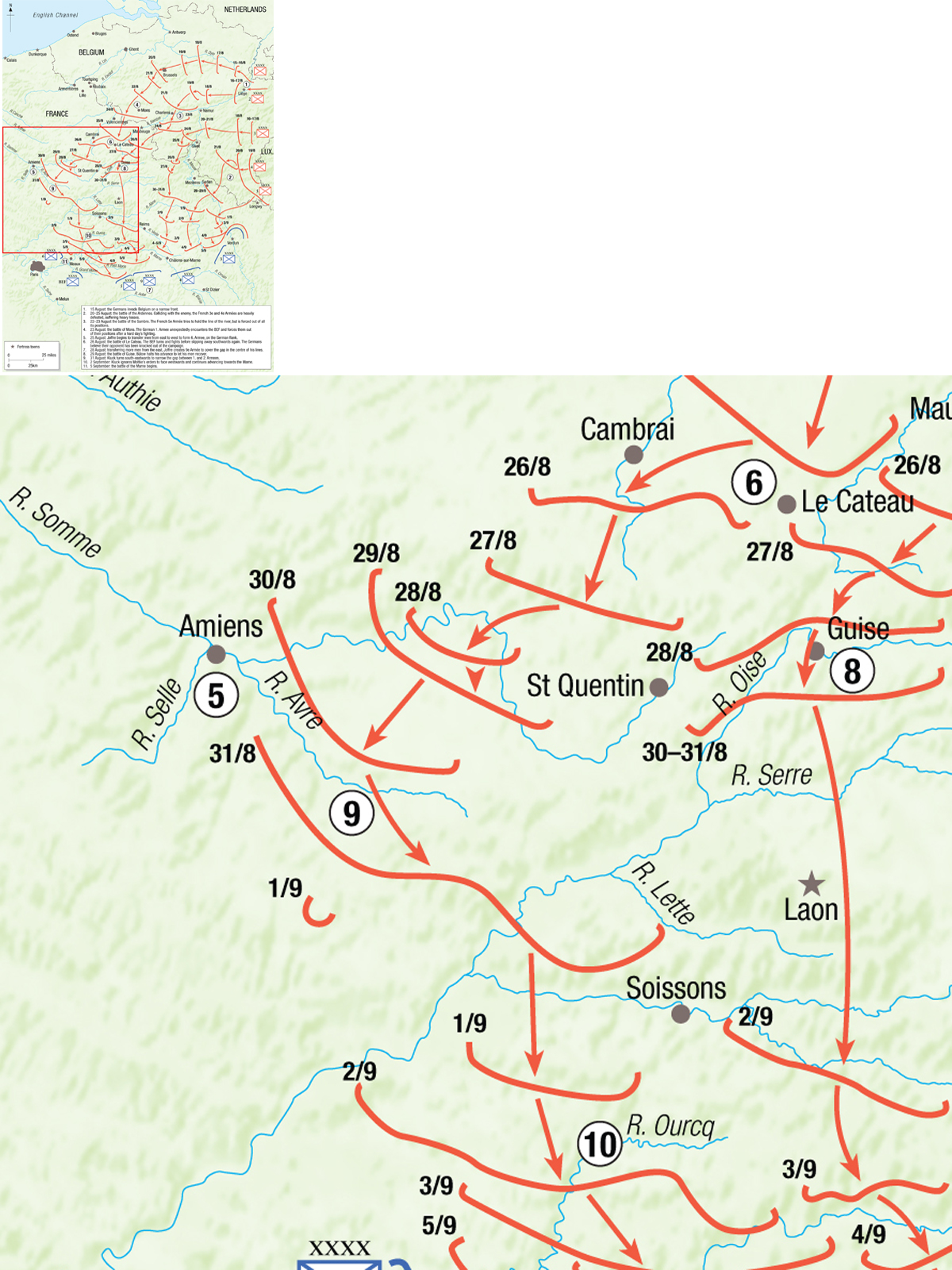

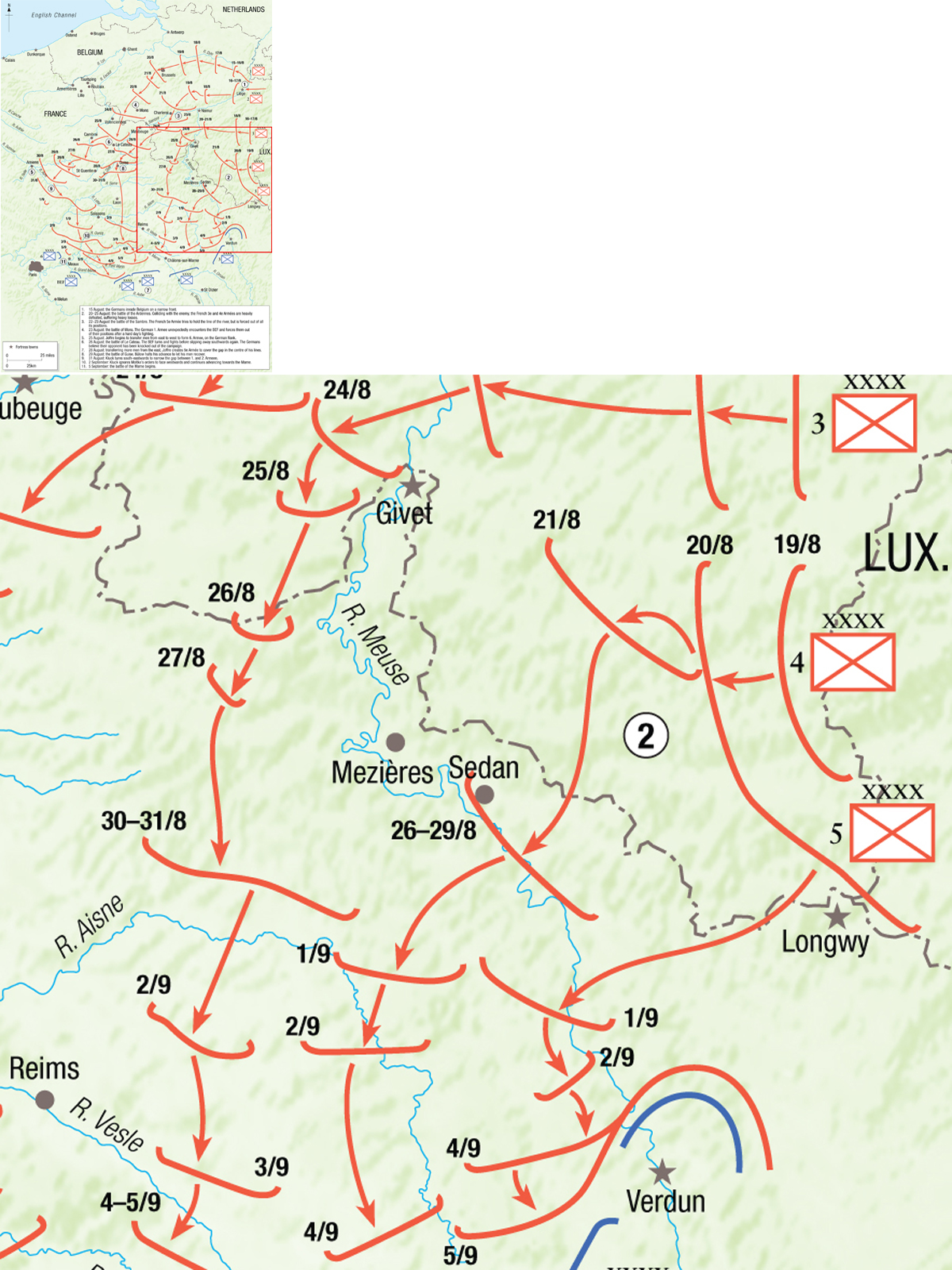

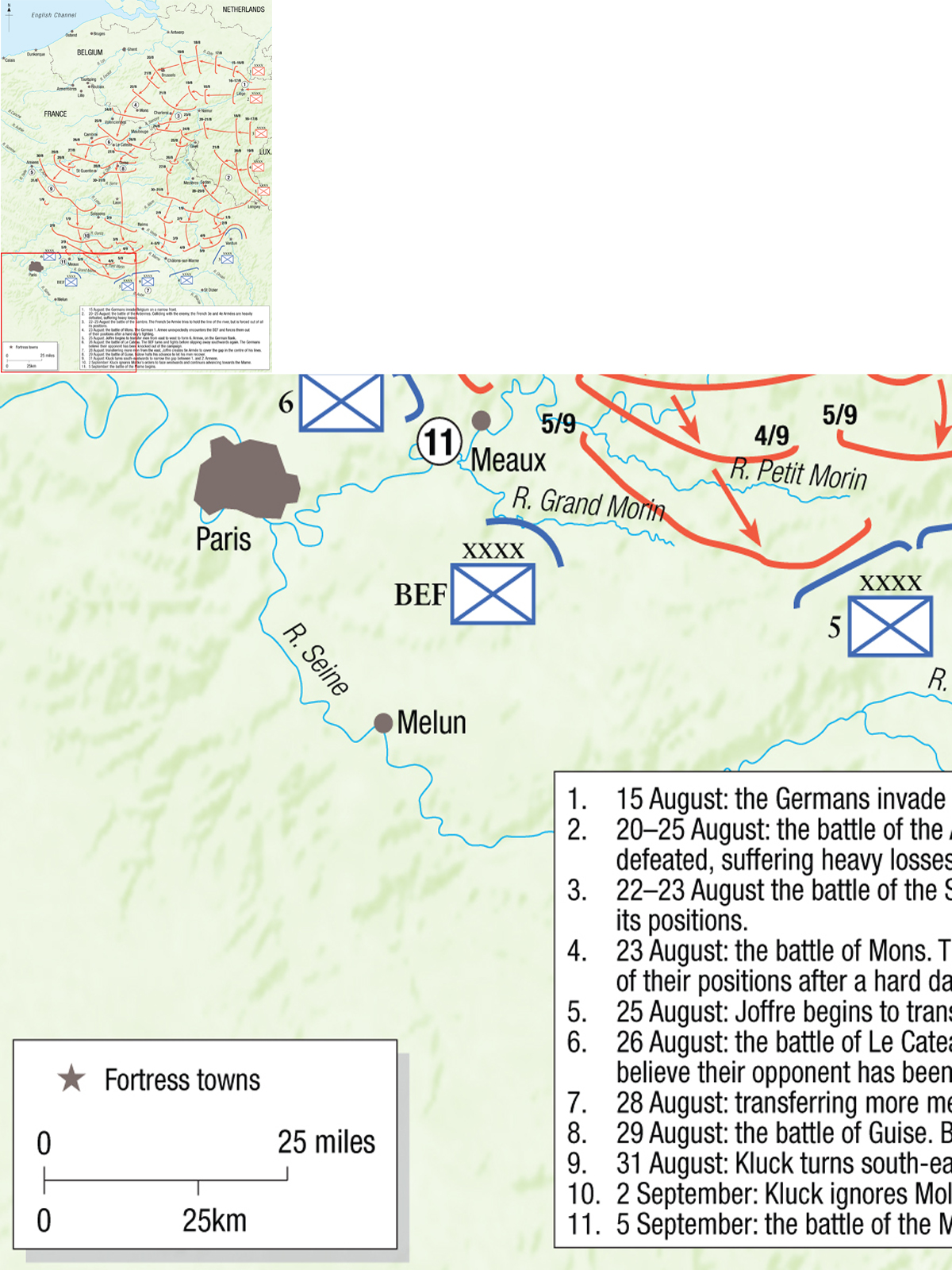

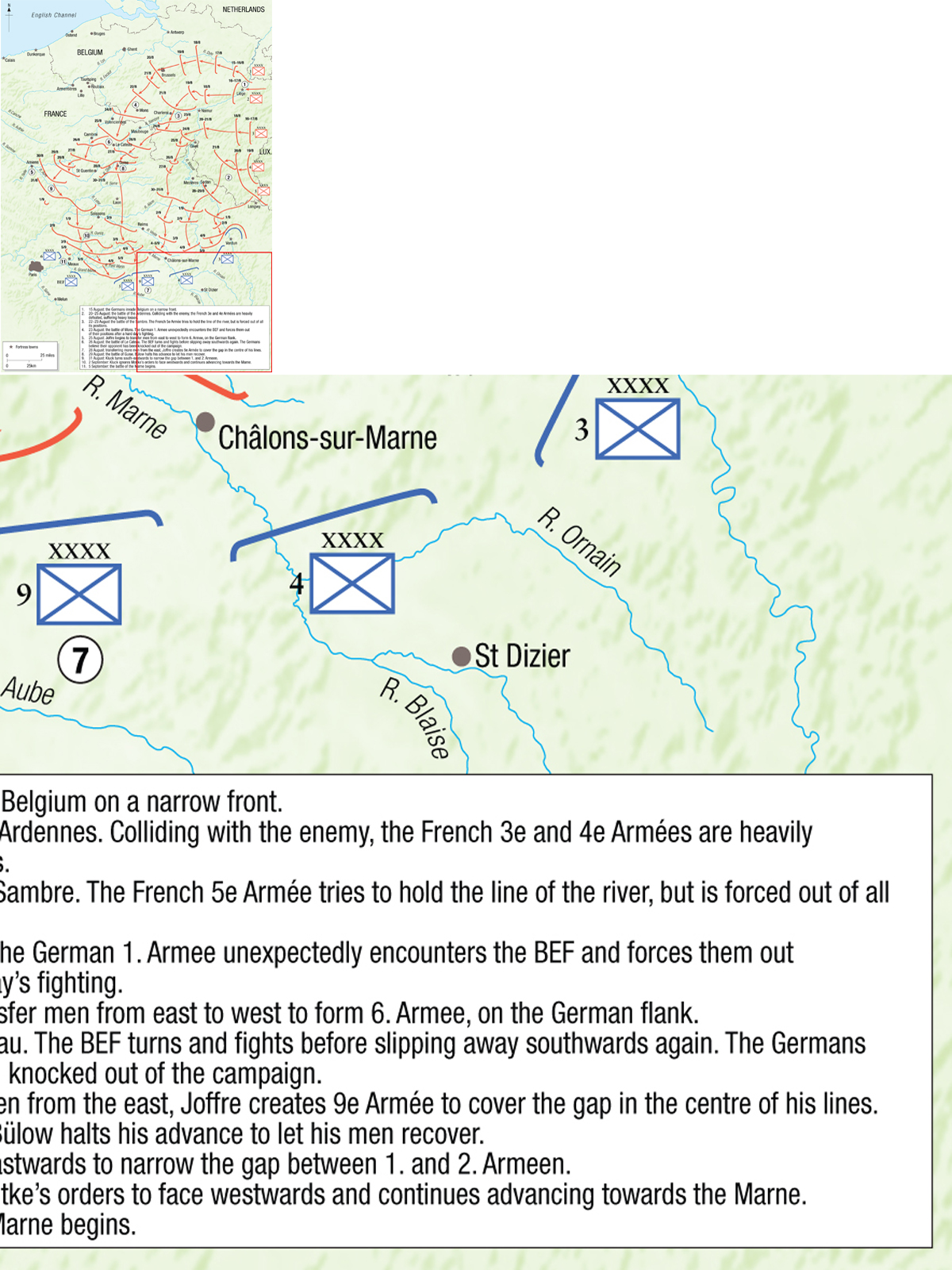

The German march to the Marne, 15 August5 September 1914

OPENING MOVES

On the opening of hostilities in August 1914 both sides were counting on a short war. For Alfred Graf von Schlieffen, writing some years earlier as Chief of the Groer Generalstab (German General Staff), the initial battles were likely to be crucial. They would decide any future conflict because of the pacifist tendencies of the majority of the European people. French field service regulations embodied similar ideas: The nature of the war, the size of the forces involved, the difficulties of resupplying them, the interruption of the social and economic life of the nation, all encourage the search for a decision in the shortest possible time to end the fighting quickly. Such thinking determined French and German war plans. Both parties aimed simply to put the maximum number of men into uniform as quickly as they could.

French actions followed Plan XVII, which became effective in May 1914. This was not primarily an operational war plan. Instead it focused on the mobilization, concentration and deployment of French forces. Four armies were assembled along the Belgian, Luxembourg and German frontiers, while a fifth was held in reserve. And the disposition of these armies in a central position was flexible enough for them to strike in a number of directions.

However, a number of constraints served to limit this freedom of action. Politically, France had no option but to take the offensive both to free the lost provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, and to fulfil its treaty obligations. (The Franco-Russian treaties guaranteed a French attack 11 days after mobilization.) At the same time it was equally important that France preserve Belgian neutrality. Joffre knew a German attack was most likely to come through Belgium. But on no account could he cross the border to pre-empt it. A succession of pre-war joint staff meetings had failed to reassure the French that Britain would take part in any land war. Invading Belgium might be all that was needed to provoke Britain into withdrawing its much-needed support.

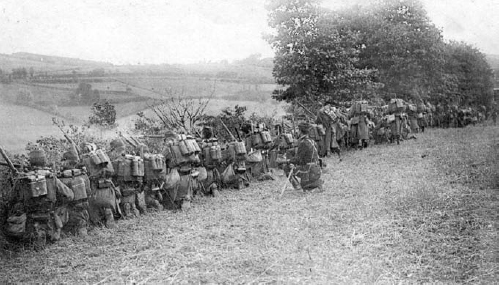

French troops on the march. In the weeks preceding the battle, a daily march of more than 20km (12 miles) was not unusual, particularly for formations on the outside of the wheeling German line of march.

French infantrymen defending the line of a hedgerow. Even in action, they are still wearing their packs. During the battles of the Frontiers, the sun reflecting off their highly polished mess tins revealed more French positions than their red trousers ever did.

While Joffre suspected a drive through Belgium, he had no detailed knowledge of German plans, and little idea of the exact size and strength of the forces he faced. Crucially, his experience of French reserve units led him to underestimate the capabilities of their German counterparts. The French Army was reluctant to place its own reserve units in the front line. Pre-war opportunities to keep these units up to a full pitch of training and readiness had been few, and it was feared the reserves would be unable to stand up to the stress of combat. Joffre assumed this also held true for his enemy and calculated that the Germans had insufficient troops to mount a strong attack through Belgium. Their main effort would therefore have to come further south. Even when French intelligence services provided a complete German order of battle, Joffre remained unmoved. Noting the lower establishments of German reserve divisions, particularly in artillery, he concluded that these formations were not intended to play a full part in battle.

But Joffre was wrong; the scale of Germanys ambitions meant that its reserve formations would play a key role from the outset. In contrast to their opponents, the German reserves had benefited from regular periods of peacetime training and their performance in combat would more than justify the decision to include them in the front line. With plenty of men available, the Germans had ample resources to mount their main attack through Belgium.

The German plan followed ideas outlined by Schlieffen in a memorandum of 1906, which suggested an advance through Belgium as a means of circumventing the formidable obstacle presented by the line of fortresses defending the Franco-German frontier. Indeed, to bypass the great frontier redoubt of Lige, Schlieffen was even prepared to invade the Netherlands. Pinning the French right in its fortresses along the Meuse, the Germans would first advance in a great curve through Belgium and northern France. Then sweeping around Paris they would go on to roll up the French armies and crush them against the Swiss frontier. Key to the plan was speed. The Germans were seeking at all costs to avoid a war on two fronts. They judged that the French would be quicker into the field than their Russian allies, so it would be vital to deal them a knockout blow first before turning to meet the threat from the east.

French infantry advancing. This is almost certainly a pre-war shot. But given the relatively close order demonstrated here it is unsurprising that casualties were so heavy.

Schlieffens successor, Moltke, accepted the strategic assumptions behind the plan, but made several important revisions. Firstly he abandoned the invasion of the Netherlands, judged politically unwise. This had a dual effect forcing the German right to advance on a restricted front across the short Belgo-German frontier and making it important to capture Lige as quickly as possible. Then, anticipating that France would make the first move by invading Alsace and Lorraine, Moltke acted to bolster the defence of the disputed provinces by transferring troops from his right to his left.

International tension was growing during the summer of 1914. On 1 August France issued its mobilization orders. But, anxious not to appear the aggressor, its commanders were ordered not to encroach within 10km (6 miles) of the Franco-German border. The following day small parties of German soldiers crossed that frontier and on 3 August Germany formally declared war on France. Then on 4 August German troops crossed over into Belgium finally provoking Great Britain into declaring war on Germany.