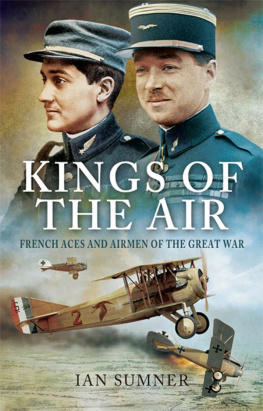

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

PEN AND SWoRD AVIATIoN

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Ian Sumner, 2015

ISBN 978 1 78346 338 1

eISBN 9781473857339

The right of Ian Sumner to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Maps

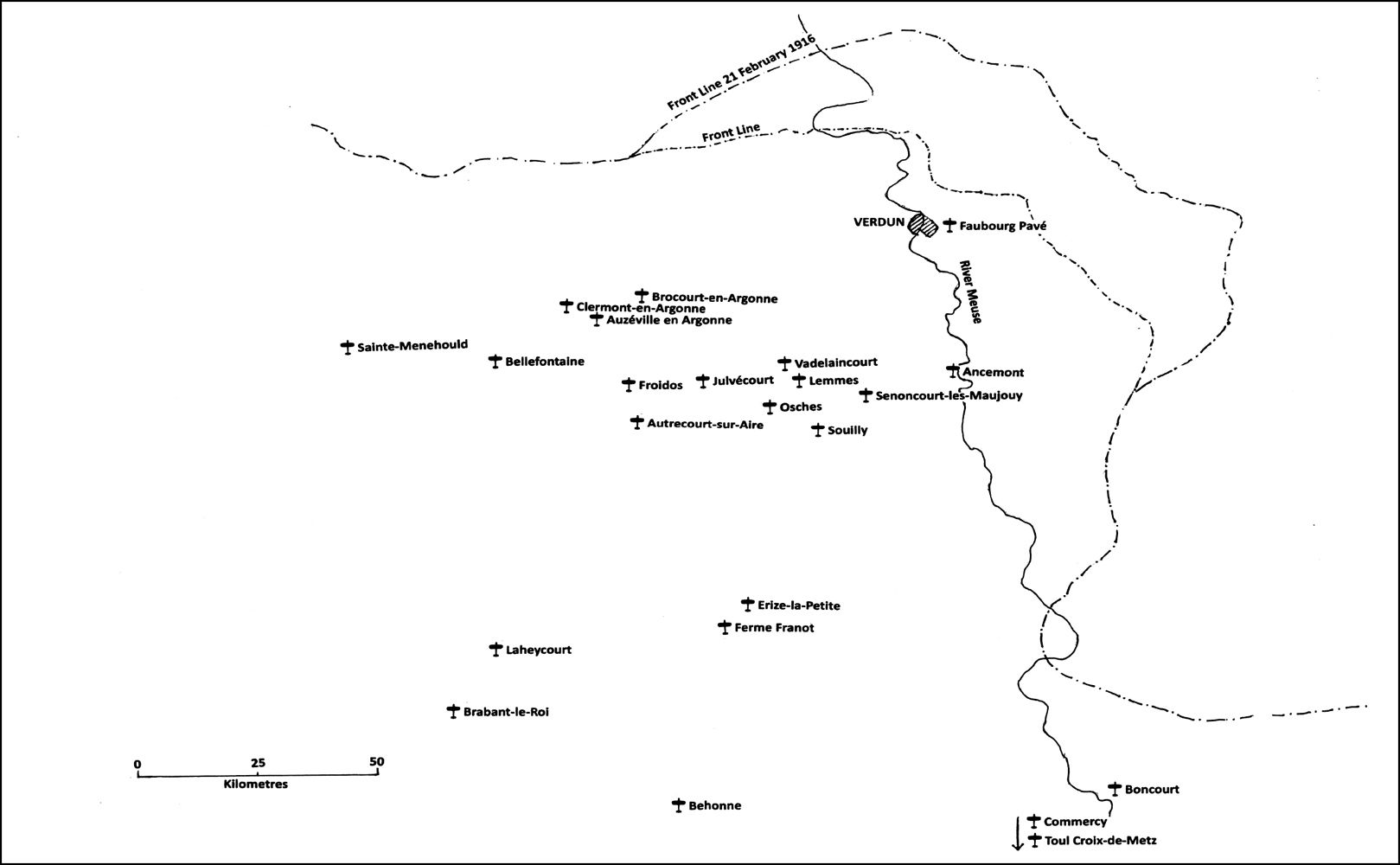

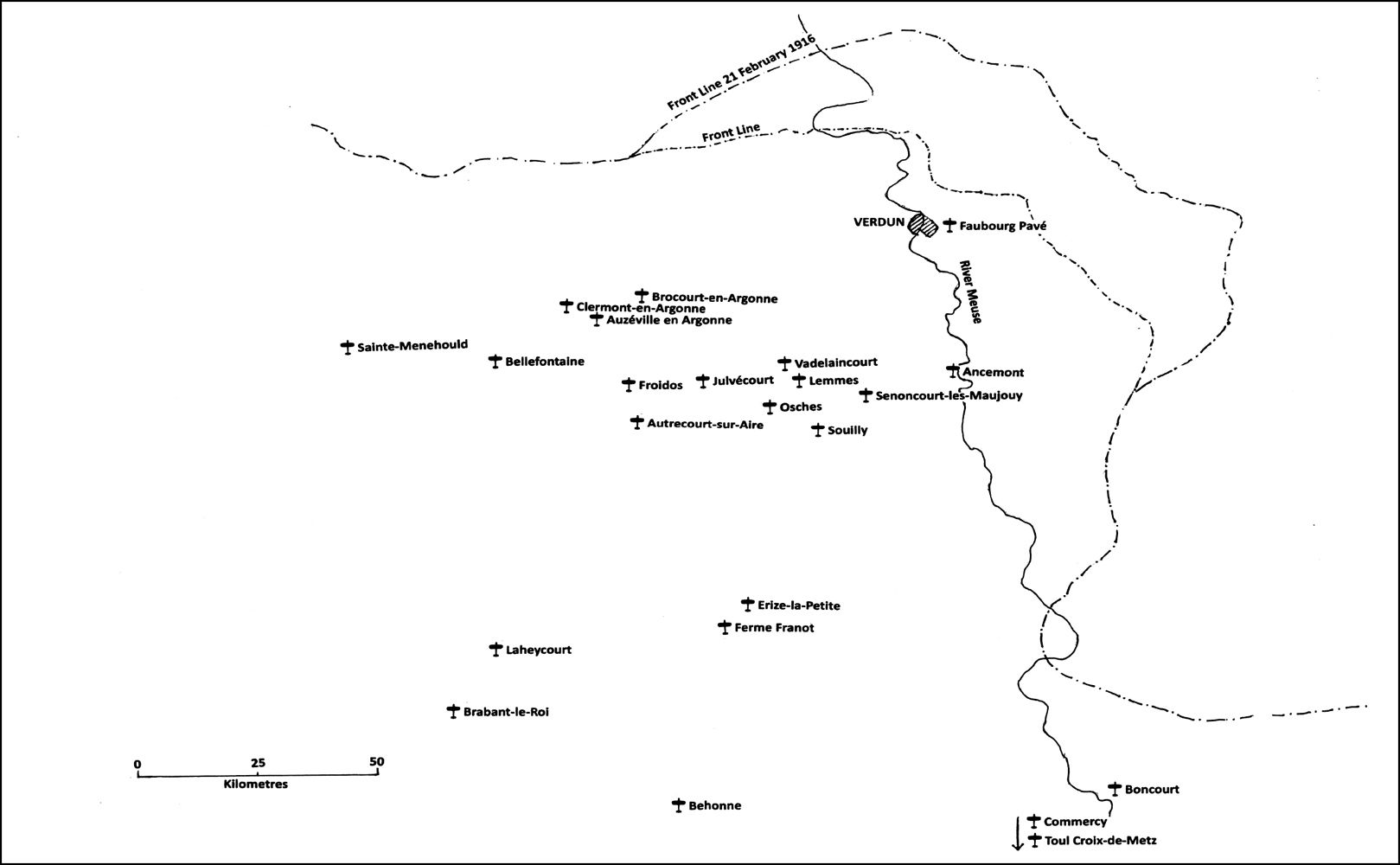

Map 1. Airfields of Verdun, 1916

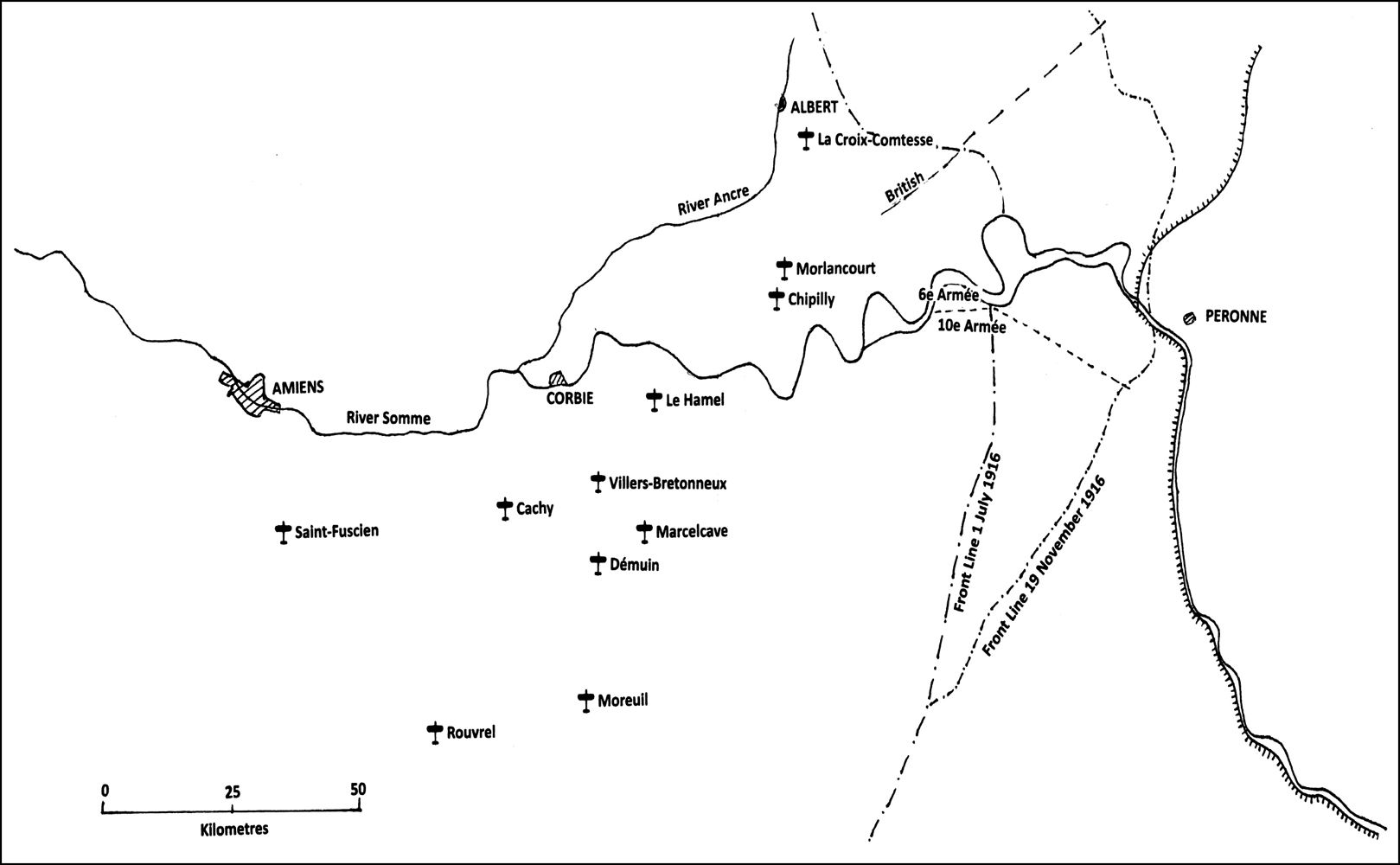

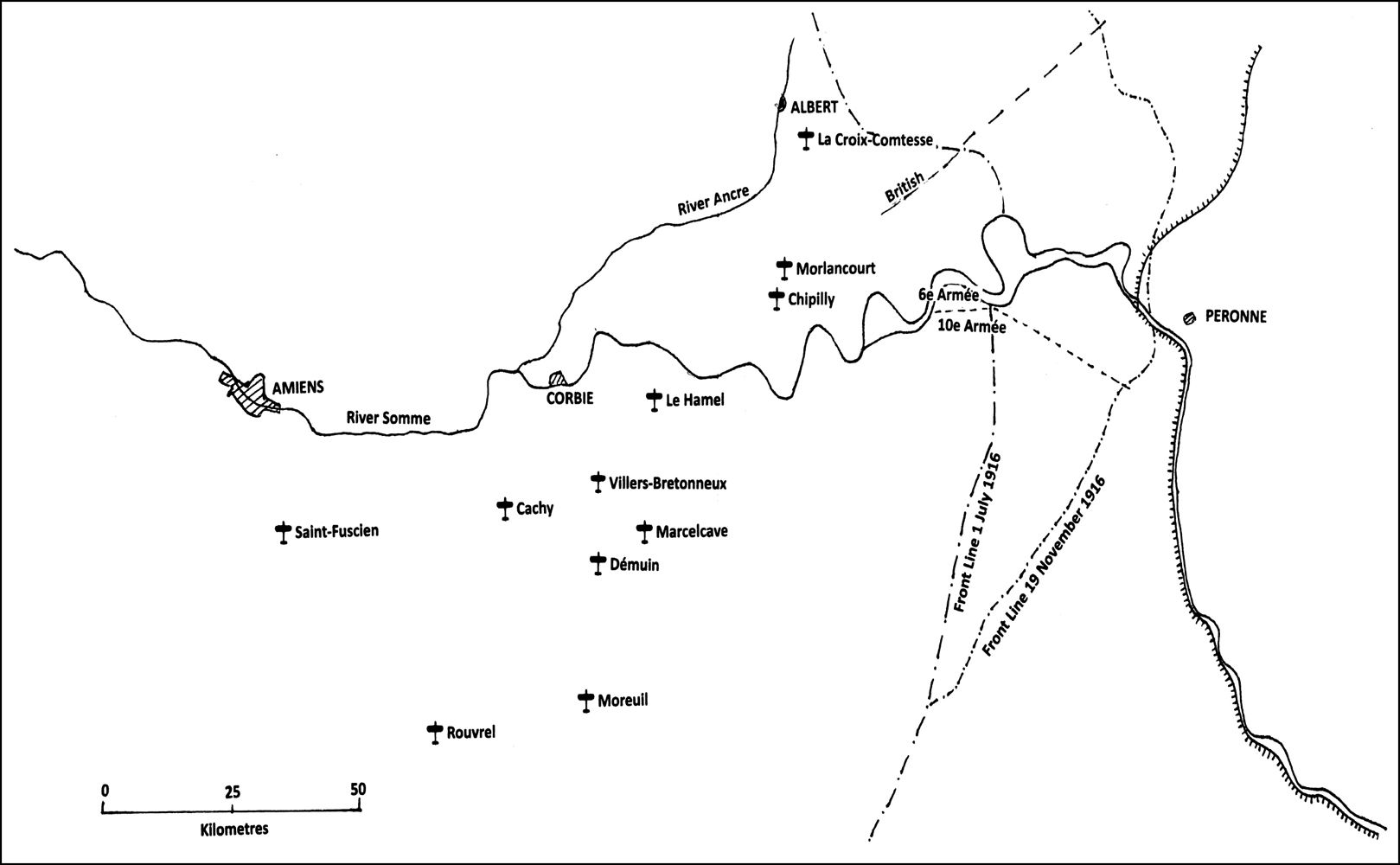

Map 2. Airfields of the Somme, 1916

Introduction and Acknowledgements

When man first took to the air in powered flight in 1903, soldiers and politicians were quick to recognize the military potential of the new technology. Over the next decade aircraft developed rapidly in power and speed, while armies faced the challenge of creating an aviation service, positioning it within the existing chain of command and evolving a doctrine to govern its use. None of these issues had been resolved on the outbreak of war, but over the next four years French aircraft progressed to become a weapon integral to the ultimate allied victory, laying the groundwork for operational developments such as fighters, strategic bombing and photo-reconnaissance, which later became standard in the Second World War.

So novel was the experience of flight that many airmen still regarded their new surroundings with awe: This sea of white really is a beautiful sight, mused Charles Delacommune (C66). Its idyllic, seductive, hypnotic. But dont linger. Like the treacherous oceans, it too claims its victims, trapping them in an instant in a cage of frosted glass. The light is worse than night. Hazy, bleached of all colour it burns the staring eyes. The engine drones dull and distant. The mountings wail mournfully. Its like a descent into the void, destined for death. In the world of the clouds you have no desire to violate nature. Discovering perfection, you are gripped by the same feelings of reverence as the explorer who penetrates the mysterious virgin forests or the lonely desert sands.

The war saw an enormous increase in the numbers of men taking to the skies. By August 1914 only 487 officers and other ranks had gained their military wings; by November 1918 some 16,546 pilots had qualified the last of them, Adrien Valire, on 11 November. In 1914 some 134 trainees passed through the system; during 1918 no fewer than 6,909 pilots qualified, 40 per cent of them going to fighter squadrons, 33 per cent to army corps squadrons and 15 per cent to bombers. Less than 20 per cent were married, and the majority hailed from an urban rather than an agricultural background, perhaps employed in a manufacturing (often metal-working), commercial or administrative job, or still a student. Most possessed their school-leaving certificate, the certificat dtudes primaires , the minimum required to pass the obligatory theory test, and a substantial minority had, or were studying for, a higher level qualification the baccalaurat (around 33 per cent) or a degree (around 20 per cent).

Over the course of the conflict 4,745 members of the aviation service and 594 members of the balloon service were reported killed or missing. A death rate of 1 in 28 appears to compare favourably with rates of 1 in 13 for the cavalry and 1 in 4 for the infantry. However, only a relatively small proportion of the service actually saw action in the firing line, whereas virtually every member of an infantry regiment was at risk. By comparison with the infantry, fewer of those killed were officers 21.6 per cent in aviation, 29 per cent in the infantry and losses were more heavily weighted towards the later years of the conflict. The infantry suffered the majority of its losses (68 per cent) between 1914 and 1916; in contrast, 80 per cent of front-line aviation deaths took place during the principal set-piece battles of Verdun and the Somme (1916), the Chemin des Dames (1917) and the defensive and offensive campaigns of 1918 with over half (51.7 per cent) of all losses incurred in the last year of the war.

The purpose of this book is to tell the story of these airmen in their own words. In my previous book, They Shall Not Pass: the French Army on the Western Front, 19141918 (Pen & Sword Books, 2012), I observed that Contemporary testimony provides an immediacy often lacking in formal accounts, but it is not without its dangers. Events and emotions remembered years after the event may be recalled imperfectly or coloured by later experience, and this statement remains equally valid here. In the case of aviation, however, these dangers are compounded by the adulation accorded to aircrew, and to fighter pilots in particular, both during and after the war, resulting in accounts which sometimes prize atmosphere over accuracy. The aviation service represented only a very small element of the French army, so fewer personal accounts were written by airmen. Many interviews appeared in the weekly magazine La Guerre arienne illustre , first published in 1917, and its successor La Vie arienne illustre . These contain many useful insights, but it is important to remember that they worked under a censorship regime.

The basic unit within the aviation service was the squadron ( escadrille ), consisting of six aircraft in 1914, ten in 1916 and fifteen in 1917. At the start of the war each squadron acted independently, reporting to an army or army corps commander. In December 1914 a number of bomber squadrons were combined into bomber groups ( Groupes de Bombardement ) of three or four squadrons each. From the spring of 1916 a number of fighter squadrons were placed in ad hoc groupements for operational or tactical reasons, and in November 1916 permanent fighter groups ( Groupes de Combat / Groupes de Chasse ) were created. Over the next year or so, provisional groupements were created from time to time, combining several groups under a single commander as the local situation required. In February 1918 larger formations, escadres , were created from three bomber or four fighter groups. In May of the same year two fighter and two bomber escadres plus a reconnaissance group were combined to form the Air Division.

Each squadron was numbered sequentially on its creation, although several renumberings took place during the war, and some units changed their number on more than one occasion. Each number was prefixed by a letter or letters to indicate the principal aircraft type operated by the squadron. One squadron might have a succession of these prefixes for example, the third squadron changed its designation from BL3 to MS3, N3 and SPA3 as it was re-equipped with different types. The prefixes were not standardized at the time: for example, contemporary usage prefixes SPAD squadrons with either S, Sp or SPA. I have compiled my own standard list and all prefixes employed in this book are given in .

Next page