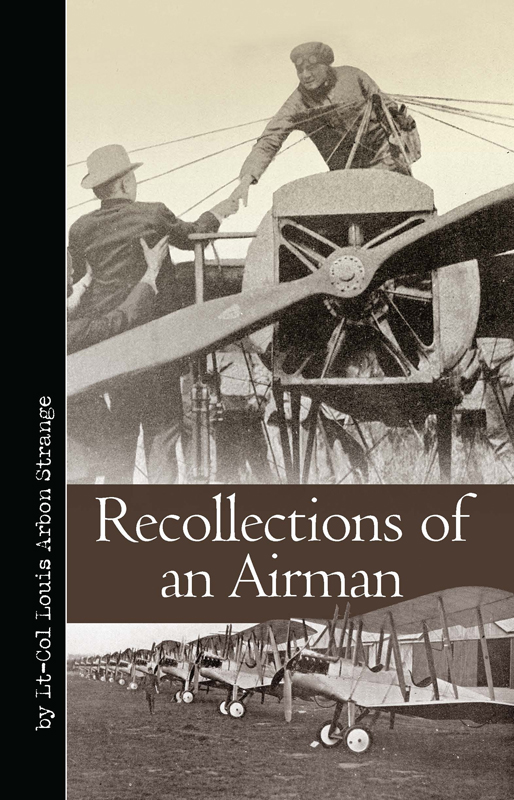

This edition of Recollections of an Airman is published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2016 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

and

10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford OX1 2EW, UK

A Greenhill Book

A Greenhill Book

Copyright Louis Arbon Strange, 1933

Typeset & design Casemate Publishers, 2016

ISBN 978-1-61200-386-3

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-61200-387-0

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress and the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in the United States of America

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Fax (01865) 794449

Email:

Dedication

To a luckless but not fameless

generation

F OREWORD

If these recollections help only to show the futility of war amongst nations my purpose is served. If this generation can achieve the restriction of aircraft for warlike purposes and confine their uses to sufficient and adequate police work, it will have done well. This is a futile hope unless by means of extensive encouragement of civil flying, ordinary men and women of all classes can mingle on their week-end holidays with those of any other nations, at no more expense than they do now at their own seaside resorts. When that day comes, and it can come to-morrow if the will is there, war will be less difficult to avoid.

L. A. S.

C ONTENTS

L IST OF I LLUSTRATIONS

APPEARING BETWEEN PAGES 108 AND 109

C HAPTER 1

EARLY DAYS

P erhaps the most vivid of my childhoods memories is that of a freshly ploughed field between a farmhouse and a mill, close by the river Stour, in Dorsetshire. On a pony which my father had just bought for us I sat bareback behind my eldest brother, Ronald, whose waist I clutched frantically. I suppose I must have been about six years old at the time.

My father held the pony on a long rein and was making it trot and canter round. He knew that we would come to no harm on the soft ploughed soil when we fell off, as we were bound to do sooner or later. All the same we were both thoroughly frightened when it happened, and I believe that this incident made Ronald decide to become a sailor. Often a trivial occurrence can be the turning point in a mans life, and the event which ultimately launched me off into the air was a kick from an old sheep with foot-rot, which I was trying to cure.

Both my father and mother came from families that had been on the land for many generations. My mother used to tell us stories of the days when her grandfather hunted Baron Rothschilds hounds in the Chilterns and France, and I remember how fascinated we children were with the pictures she drew of him in his hunting kit. He was a great favourite at all the balls and county functions of his time, because he was blessed with more than his fair share of good looks, in addition to being known as a fearless rider and a great huntsman. When he was in England he grew grass to make hay for a number of hunters that were put out to graze for the summer on land which is now Hendon aerodrome, where I learnt to fly.

My father, too, had a number of stories. He loved to tell us of great hunting runs in Dorsetshire with Mr. Radcliffes foxhounds, Lord Wolvertons deerhounds and Mr. Farqharsons harriers. Very stirring to us children were also his tales of the way in which the Dorsetshire Yeomanry came into existence during the Napoleonic wars and the part his grandfather played in its formation. This great-grandfather of mine must have been a man of unusual strength, because my father pointed out to us the place where he had written his name on the ceiling, with a fifty-six-lb. weight hanging from his little finger.

Another tale that always thrilled us concerned a great snowstorm, still talked of in those parts, when my aforesaid ancestor rode his horse across country from Hazlebury Brian to Blandford Forum, a matter of some ten miles, on the top of frozen snow, without seeing a road or a hedge for the whole of the trip. On another occasion he bought 3000 head of sheep at a fair and walked them across country from somewhere in the Bristol district to Chichester market.

I suppose they were giants in those days. They used to think nothing of driving fifty miles to a sheep fair and arriving there before nine in the morning. When my great grandfather wanted to show Bryan, his champion bull, at the Royal Show at Oxford, he had to march him there across country all the way from Dorsetshire, and I wonder how many men would care to take on such a job nowadays.

Their horses, too, were of a breed that is not seen now. There was Black, for instance, a marvellous steeple-chaser: I wonder how many horses there are now that could give him a pound over any course. And then there was All Black, who cleared the newly erected gates at the level crossing at Sturminster; he went in and out of them just like a double fence.

My father was a great story teller, and we children had to listen to his tales and jokes over and over again when he retailed them to visitors. The anecdote that particularly sticks in my mind is one he told concerning a certain Yeomanry Dinner.

At that festivity everyone had to make a good pun or else stand a round of drinks. One of the party left late at night to drive the eight miles back to our home after having failed to think of a suitable pun; he put the pony and trap away and went upstairs to the bedroom where his wife was. Sleepily and unintentionally she murmured something that was a very apt pun.

Well done, Jane, said the worthy. Thats good enough. Then, without another word of explanation he hurried downstairs, reharnessed the pony and drove back the eight miles to the hotel where the majority of diners were putting up. But when he got there, he found that the pun had completely gone out of his head, so back home he drove to ask his wife what it was. Then off he went to tell it to the assembled company.

It was a happy time for me. In the winter holidays there were markets, fairs and hunting; in the summer ones we fished and sailed on the river. The chief thing I remember about those diversions is the feat of a huge, coal-black nigger at Woodbury Hill Fair, who lit and ate large matches. I asked him if it hurt.

Oh, yes, sah, was his reply; but it always does hurt somewhere when you have to earn your own living.

I also remember the occasion when I bought my first horse at Shroton Fair. The vendor was an Irishman, who asked seventy guineas for him, whereupon I offered seventeen.

Bedad, hes yours, yelled the fellow before I had time to change my mind. Soooold! he whooped triumphantly to his companion, and then launched into fulsome praise of the animal, which, he declared, walked just like a lady going to a ball.

Of course I joined the Dorsetshire Yeomanry. I was a member of that honourable body before I even left school, and I can remember how proud I was when I secured third place in my first point-to-point race, while another red-letter day was on the occasion of a certain run with the Portman hounds in the Vale when after an hour and forty minutes hard going I was the only person up with the hounds. It was a special triumph because the Vale men did not think much of the South Dorset hill folk. I fancy they were rather unjust to us as whenever we went down into the Vale country we were generally well up with the hounds, chiefly, I imagine, because we rode all the straighter on account of our ignorance of the country.

Next page

![Bar Wing Commander Guy P. Gibson VC DSO - Enemy Coast Ahead [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/180257/thumbs/bar-wing-commander-guy-p-gibson-vc-dso-enemy.jpg)

A Greenhill Book

A Greenhill Book