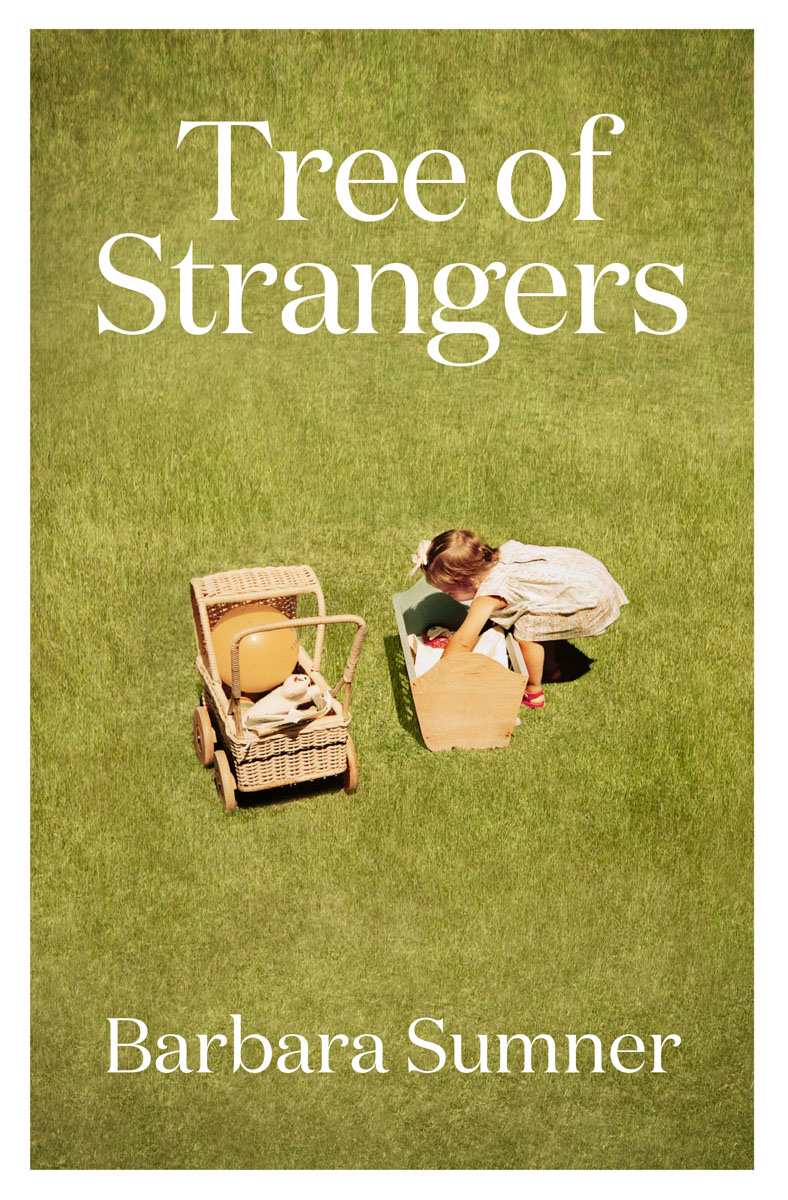

Sumner - Tree of Strangers

Here you can read online Sumner - Tree of Strangers full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Massey University Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Tree of Strangers

- Author:

- Publisher:Massey University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tree of Strangers: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Tree of Strangers" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Tree of Strangers — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Tree of Strangers" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

All mothers are daughters.

For Pamela. For Bonnie, Rachel, Ruth, Amelia and Lilian.

R unanga, West Coast, 1983.

I live at the end of a gravel road at the top of a valley consumed by bush. Beyond our cottage, the old track has almost disappeared. Gone are the trucks that once serviced the coalmine. The bush has closed up behind them like a curtain at the end of a performance.

I am alone with the wind at night, released by darkness to rage against itself in our isolation. Every day the rain engorges the bush with a lushness that overwhelms our tiny clearing. My husband is here and my three girls. But the bush swallows them up like the road, hiding them from my view beneath a green canopy of enmity.

I wrote those words at the kitchen table in 1983, on a scrap of paper that survived the many later purges of my life. An embarrassing early version of an unsent letter to my mother. The whole world hung on those words. A letter to the mother Id never met. The mother Id dreamed of and longed for. The mother I had just found. But how do you convey your life in a few sentences when almost every memory is missing?

It wasnt as if Id woken from a coma at twenty-three and found myself stuck in a loveless marriage with three small daughters. A sleepwalker committing a crime. I hovered between sleep and waking, unknowing but somehow not innocent.

Generalised dissociative identity disorder, my therapist calls it. Generalised because it is not total. I have fragmented memories: mountain tops poking through clouds. Dissociative because the physical and emotional world often feels unreal. Daydreaming on steroids. I forage for identity or assume new ones, sometimes at the same time. In short, I am an unreliable narrator of my own life.

But diagnosis is good. In adoption circles, we call it the fog.

Mavis and Max, my adopting parents, were instructed to tell me early and to act as if I was born to them. A birth certificate names them as my biological parents. Paper proof of parentage. No one asked what it might mean to adopt a stranger or to be that child. Stripped of meaning or context, youre adopted became a crack in my mind and thats how the fog got in.

Even now I still lose memories as easily as small change. But I remember the night of the phone call.

In Runanga, on the West Coast of the South Island, there was always a storm brewing out to sea. Bruce, my husband, sat in the depths of his chair, his reading lamp held together with tape. We were not television people. Our three girls were asleep in the next room.

The bath was my refuge. I wrapped the plug in a rag and wedged it into the hole. Rusty water struck the pitted cast iron. I sat on the edge of the tub, the chill of the house creeping up, while I waited for the surface to flatten before slipping beneath its perfect skin.

Bruce knocked on the bathroom door. Rain slamming against the window had drowned out the phone. His voice was slow with annoyance. I wrapped a towel around me and went to the kitchen.

This is Jeannie. The voice was deep and gravelled.

Almost four years earlier Id looked into the scrunched face of my first child and seen an inkling of our likeness. It was the first time Id seen someone I was related to. I wrote to Social Welfare, the first of many letters. A few were recently returned under court order. Held on file through every welfare department incarnation. Sad, pleading messages. Please tell me about my mother. Reading them now, Im struck by their rawness and intimacy. I imagine the bureaucrats who read them. Their replies were formal. We have no information on your mother. We are unable to help you.

The storm diminished. Hi? I felt like I was shouting down the phone.

Is that your husband? Jeannie rushed on. Not very friendly, is he?

Hes reading. He doesnt like the phone much.

Jeannies laugh was a short burst of sound, one sharp note on top of the other. I had no idea why Id told a stranger about my husband.

From the haloed chair Bruce cleared his throat. The moon emerged, casting long shadows across the lawn.

Im replying to your letter, Jeannie said. How did you find me?

Another letter. A random chance that seemed like such a long shot I could hardly believe she was calling.

T he library book on finding biological family lost to adoption had advised digging deep to find a dropped clue, a lost memory. Even opening the book had infused me with a sense of disloyalty as indelible as a birthmark. The title is gone. But the stories of lives completed in reunion, the secrets of their stranger adoptions stripped away, brought me to tears. A memory rose up, precise and whole. Maviss sister had been a nurse for the doctor who delivered me. She was consoling Mavis at the Formica table in our kitchen. I was fourteen and surly.

What do you expect? the aunt said, her voice hushed over teacups as I lurked in the hallway. Her mother was a model. Youve heard the stories She sucked on her cigarette when she saw me.

It was no more than a crumb.

At the Greymouth library, I took down the Auckland phone book and looked under M for Model. Nothing. But there was a Modelling Society in Wellington.

An extravagant toll call in the calm of early afternoon when the girls were napping and playing.

Do you know anyone involved in modelling in the late 1950s? I asked the blithe young woman who answered.

You better call Maysie, she said. Maysie Bestall-Cohen. You know.

I didnt know, but Maysie turned out to have been the doyenne of the emerging fashion industry. She sounded kind. The Modelling Society did not get going until the early 1960s, she said. Write to Jeannie Gandar, she started everything at the Fashion Fiesta in Upper Hutt in 1961. She knew a lot of girls.

I wrote to Jeannie at the Wellington Polytechnic, where she taught clothing design. I included a family studio portrait Bruce had won in a raffle. We were standing together in front of a mottled background, new baby Ruth in my arms. Rachel, the middle one, smiling whimsically, while Bonnie gazed down the lens. With nail scissors I trimmed away Bruce and the girls, until I was alone against the painted backdrop. Months passed, and I gave up any hope of a reply. After all it was an impossible task. I possessed just two facts about myself: my date of birth and Her mother was a model.

I m replying to your letter, Jeannie said in her deep voice. At first I thought, how ridiculous. It happened to so many girls I knew. She drew breath and I was sure she was smoking. To be honest, I threw your letter away. But something woke me in the night and I thought: Thats Pamelas girl. Has to be. The likeness is uncanny.

My chest tightened. Pamela. Her name is Pamela.

I got up and drove to my office and saved it from the bin as the cleaners came through.

I had the impression Jeannie was tall, imposing. The kind of woman everyone noticed. She explained shed taken months to call because shed been researching. Shed lost touch with Pamela but found Fred, Pamelas father, living in Waikanae. He remembered the name of the doctor in Napier.

When Jeannie was sure, shed called Pam in Madrid. Just the word conjured something in me. Madrid. Spain. The opposite of coal-town Runanga with its shuttered mine, roaming dogs and born-again Christians.

Its remarkable, spooky even, Jeannie laughed. You writing to me, and me knowing your mother.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Tree of Strangers»

Look at similar books to Tree of Strangers. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Tree of Strangers and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.