PREFACE

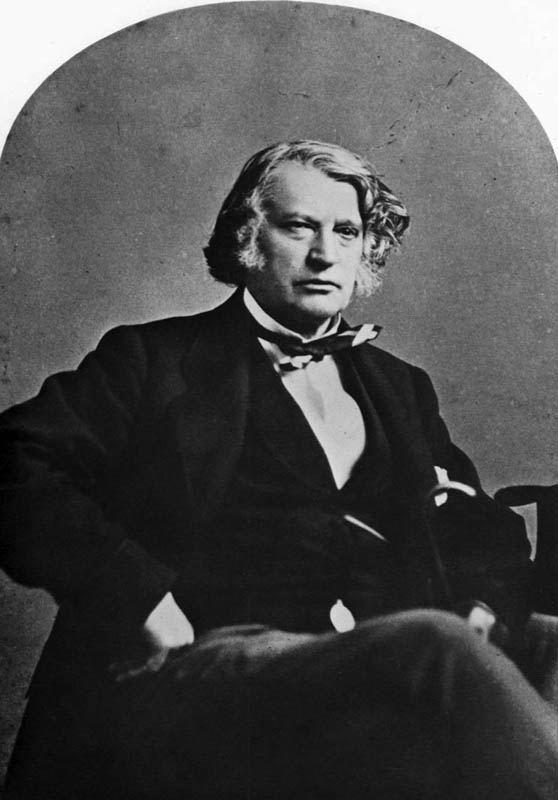

This book is an account of the career of Charles Sumner during the Civil War and Reconstruction period. It is long because Sumners activities during those years were influential and deserve extended discussion. The principal antislavery spokesman in the United States Senate, Sumner in the early years of the war prodded Abraham Lincoln to emancipate the slaves. Once that was done, he insisted that the President protect the freedmen in their liberty. In the postwar period Sumner worked unceasingly to guarantee the political and civil rights of Negroes in the South and to eliminate racial discrimination throughout the United States. Equally important, though less familiar, was Sumners role in the direction of American diplomacy from 1861 to 1871. As chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, he often exercised influence as great as that of the Secretary of State. Devoted to international peace, Sumner countered William H. Sewards belligerent propensities and, through his wide and powerful circle of correspondents abroad, discouraged European powers from meddling in the American conflict. After the war Sumner blocked the ill-advised plans of Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant for annexing territory in the Caribbean, but he was instrumental in persuading the Senate to approve the purchase of Alaska. Though Sumners influence in foreign policy was usually exerted in the direction of peace, he was also responsible, through two major addresses in 1863 and 1869, for whipping up American ill-will against Great Britain over the Alabama Claims issue.

Though the importance of these activities justifies the for it was his hope that after the tragedy of Civil War the United States would emerge as a truly civilized society.

Yet it was not the importance of Sumners ideas, or the sympathy which I have for them, that caused me to persist in my researches on this complex and often difficult man. After all, many other men of letters and men of learning in nineteenth-century America shared his aspirations. What is unique about Sumner is the way he implemented his principles. Despite the prevailing climate of anti-intellectualism, the American man of ideas in his generation had several ways to make an impact upon public policy: Emerson chose to remain a contemplative critic of society; Wendell Phillips championed lost causes; E. L. Godkin and George William Curtis served as journalistic gadflies to American complacency; Lieber and Charles Eliot Norton helped mobilize Northern opinion during the war through the pamphlets they wrote and edited for the Loyal Publication Society; Joseph Henry put his scientific knowledge at the disposal of the Lincoln administration; and, in the postwar years, Henry Adams served as closet adviser to a generation of American statesmen. Only Sumner had a successful career in politics. He alone was responsible to a constituency of voters, and he alone had to battle for his ideas in the Congress of the United States. Between the age of Thomas Jefferson and that of Woodrow Wilson, Sumner was the one American who had equal claim for distinction in the world of the intellect and the world of politics.

Much of this book is necessarily an account of how Sumnerstereotyped by his enemies as a dreamy-eyed abstractionist, a single-minded ideologistwas able to hold his powerful place in the Senate during a critical period in our history. I have tried to show how shrewdly he balanced political forces. In Lincolns administration he had to play off the President against the Secretary of State; in Johnsons and Grants, to counter the weight of the executive branch of the government with that of the legislative. Within the Senate he had to draw upon the respect his colleagues had for his expertness on foreign policy to secure a hearing for his proposals in behalf of freedom and equality. So long as his position in the national government was strong, he could scotch discontent among Massachusetts Republicans. The antislavery vanguard condoned his occasional concessions to expediency because he was in a position to do so much good in Washington, and even Massachusetts businessmen forgave Sumners radicalism on Negro rights because he was so sound on questions of currency and foreign policy. Sumners skill in preserving this equilibrium enabled him to keep his position in the Senate, and his hold on public opinion, long after most of the other early Republican leaders had dropped out of sight.

I trust that readers will understand that I am presenting an analysis of Sumners techniques for remaining in power, not an explanation of his motives for so doing. This biography is not a political interpretation of Charles Sumner (i.e., an argument that he was motivated principally by the desire for political office and power). Long before the events traced in this book, Sumners I described the forces that molded him. In the present volumewhich is a completely self-contained work and may be read without reference to the earlier bookI attempt to show how a man with Sumners ideas and motives was able to operate within the American political system.

It may also be proper for me to remind readers that this is a biography, not a general history of the Civil War and Reconstruction era. I have included only such material as I believe necessary for an understanding of Sumners career. The following pages, therefore, do not summarize the provisions of, say, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 or the Treaty of Washington, important as these matters may be.

Nor have I thought it necessary in this book to discredit again hoary racist stereotypes about the Civil War and Reconstruction period. For more than a generation historians have rejected the notion that Reconstruction was what Claude G. Bowers called the tragic era, during which malignant Radicalslike Sumnerthrust the good whites of the South under the control of knavish and barbaric blacks. I assume that my readers will know that this old interpretation is wholly untenable. Lest there be any obscurity about my own position, perhaps I ought to say that I do indeed believe that the postwar years formed a tragic eratragic in the sense that we failed to adopt Sumners principles and failed to reconstruct our whole society on the basis of equal rights for all. This is a position that I have argued consistently in a series of books and articles since 1944, and I do not think it useful to repeat myself here.