Publication supported by the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book and its author have benefited from the generosity of many scholars and professionals, including old friends, new friends, and kindly strangers. I would especially like to thank those who read some or all of the manuscript at its various stages (including as articles or proposals) and offered advice and encouragement. That list includes Martin Nedbal, Cindy L. Kim, Lara Housez, Cristina Fava, Jennifer Ronyak, Doug Shadle, Christina Bashford, Daniel Beller McKenna, Mark Evan Bonds, Carlo Caballero, David Gramit, Charles Youmans, and many others. The idea for this book began with my master's thesis, completed at the University of Northern Colorado under the guidance of Jonathan Bellman and Deborah Kauffman, and continued with my doctoral dissertation, advised by Ralph P. Locke at the Eastman School of Music. The present, expanded treatment of nineteenth-century chamber music and its audiences was made possible by research funding from the Pennsylvania State University, which provided travel support for archival research, and from Georgia State University, which provided for summer writing. I am grateful to my GSU colleague Curtis Bryant, who engraved the musical examples for .

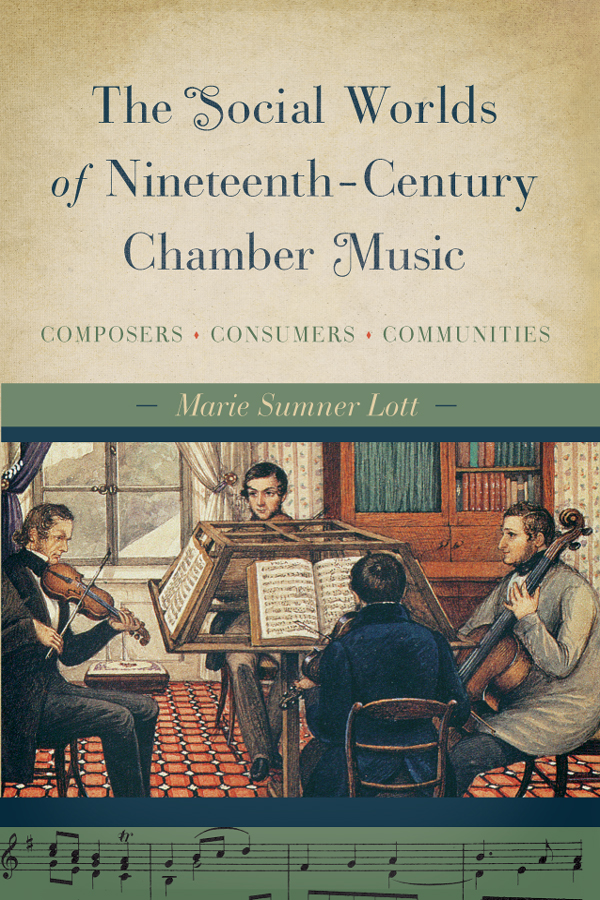

Laurie Matheson, editor in chief at the University of Illinois Press, has been patient and kind as she shepherded me through my first book-publishing experience. Her colleagues at the press have been a joy to work with, and I hope that I have not caused them more than the usual headaches associated with an author's first project. Dawn Durante and Marika Christofides helped me wrangle files, contracts, and other digital forms of paperwork. Mary M. Hill did a wonderful job with the copyediting. Dustin Hubbart's art team designed a beautiful cover.

I am also indebted to the libraries and archives that preserve documents and odd items for decades, just on the off chance that someone might want to see them one day. I thank the staff and librarians at the Sibley Music Library (especially Jim Farrington and Alice Carli, who spearheaded that institution's digitization project, enabling you, dear Reader, to access most of the obscure scores discussed in this book online) and the libraries of the Pennsylvania State University and the Georgia State University. Judith Picard, archivist at the Lienau-Schlesinger publishing house in Frankfurt am Main (Germany), provided guidance and access to rare business records and scores from the Schlesinger archive. Warmest thanks to her for helping me to understand the print records and to read the terrible ; their staff was patient and accommodating in the summer of 2009, and they have graciously allowed the reproduction of images from the Peters and Hofmeister archives. For permission to reproduce paintings in the introduction, I would also like to thank the Bridgeman Images Group, Art Resource Group, and Superstock.

Portions of some chapters have been published in earlier versions. Some of the analysis in appeared as Changing Audiences, Changing Styles: String Chamber Music and the Industrial Revolution in Instrumental Music and the Industrial Revolution (Orpheus, 2010). Some of the discussion of Brahms's string quartets was published in At the Intersection of Public and Private Musical Life: Brahms's op. 51 String Quartets in the Journal of the Royal Musical Association (November 2012), though that article also discusses movements from these works that are not examined in this book. An earlier version of the discussion of Brahms's string sextets was published as Domesticity in Brahms's String Sextets, Opp. 18 and 36 in Brahms in the Home and the Concert Hall (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Finally, I extend thanks to several people who have shaped this book indirectly by giving me examples to live by and offering models of musicianship and scholarship. At every stage of my educational career I have been blessed with wonderful teachers. In addition to Ralph, Jonathan, and Debbie, I wish to acknowledge the profound gratitude I feel toward Marian Wilson Kimber, Wilbur Moreland, and Dana Ragsdale, all formerly of the University of Southern Mississippi.

INTRODUCTION

String Chamber Music and Its Audiences in the Nineteenth Century

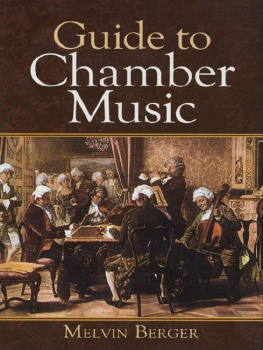

On a chilly winter evening in Berlin, a group of men sits in a candle-lit room playing a string quartet. They are joined by a middle-aged woman dressed in black, who sits as close as possible to the ensemble in a comfortable upholstered armchair. She looks down and keeps her body still, leaning her cheek on her hand; she is mesmerized by the music she hears, giving it her full attention, perhaps closing her eyes to shut out distractions. The room is a large one with high ceilings, tastefully and expensively decorated with fine wallpaper, paintings, and draperies. Near the top of the walls, a series of marble busts have been installed, peering down at the room's inhabitants. At the edges of the room, tables and chairs have been placed at a respectful distance, and more onlookers and listeners sit there, also giving their full attention to the quartet.

Earlier in the day, in Frankfurt, a similar group of men gathered to play a string quartet. They, too, sat in a well-appointed room surrounded by fine fabrics, carpets, paintings, and bibelots. Their room was somewhat smaller, cozier even. At the center of the space a four-sided music standthat particular piece of furniture that denotes that a true music lover lives herestood at the ready with the parts opened. The four gentlemen, now seated in their places, looked to the violinist, who, with one quick motion, breathed in sharply and placed his bow on the string.

On the surface, these two scenes, common enough in the nineteenth century to be immediately recognizable from a variety of paintings, drawings, or descriptions in novels and stories, describe two iterations of the same type of occasion: a domestic performance of string chamber music in an upper-middle-class home. But upon further consideration, two very different events may be inferred from the visual cues described. In the larger room, the high-art and culture signifiers in the form of classically inspired busts and, most importantly, the presence of a select audience give the impression of a concert-like event in a private space. The image : Carl Johann Arnold's watercolor Quartettabend bei Bettina von Arnim from 1856, which depicts the violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim and his quartet playing at the home of Arnim (ne Brentano), the respected Romantic poet and author. It exemplifies the sort of semiprivate performance that was common in the nineteenth century, a holdover from the previous century, when aristocrats like Arnim would hire or invite professional musicians to perform for their friends and families. In the later era, these semiprivate events served multiple purposes, including as rehearsal trials for public performances and opportunities to cultivate connections to patrons and supporters of the arts and their institutions. In many ways, this sort of semiprivate event mirrors modern fund-raisers and by-invitation performances for patrons of the arts and educational institutions. Like its modern counterpart, the event was intended to be publicized for the benefit of both the attendees, whose social status would be elevated by their increased cultural capital, and the professional musicians (and the composers whose work they played), who would likewise gain status and publicity.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.