Prologue

Zemlinskys Vienna

I n 1867 the cornerstone of the Musikverein was laid on a wide tract of land just south of old Vienna, on ground generously donated by the Austrian Emperor. The new Society of Music was being built to replace a 700-seat hall in the city center that Viennas concert-going middle class had outgrown. The project had been entrusted to Theophil Hansen, a Dane who harbored a predilection for the architecture of ancient Greece. Hansens classically inspired design featured a three-tiered faade with arched porticos, flanked on both sides by two-story wings, all adorned with classical columns. When finished, the edifice stood stately, elegant and serene. Hansen had purposely reserved nineteenth -century opulence for the Musikvereins interior, a reflection of the high regard he, like the Viennese who would occupy its seats, held for the music itself.

Although the Verein houses five concert halls today, only two were part of Hansens original structure : a small, intimate chamber music hall the Kleiner Saal or Little Hall decorated with a temple roof, Ionic columns and caryatids, and renamed for Johannes Brahms in 1937 ; and the Great Hall the Grosser Musikvereinssaal a room capable of accommodating an audience in excess of 2000. The Great Hall, known also as the Golden Hall, was Hansens true gift to Vienna. The rectangular room blankets the listener with visual spectacle, from the caryatids in the stalls and elegant female sculptures molded atop the balcony doors, to the richly decorated golden balcony and ceiling, framed by rows of arched windows that flood the entire room in sunlight. Above it all, ceiling paintings of Apollo and the nine Muses keep watch on the music making below. But it is the rooms rich golden sound that continues to make the Musikverein an inspiring musical experience. A century and a half later, the Great Halls sumptuous acoustics remain among the best in the world.

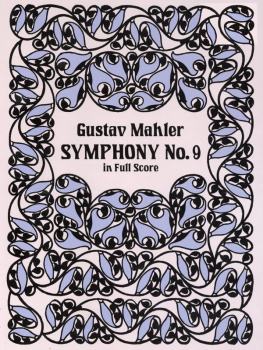

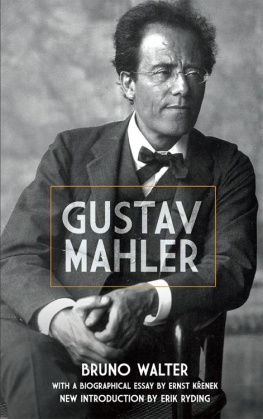

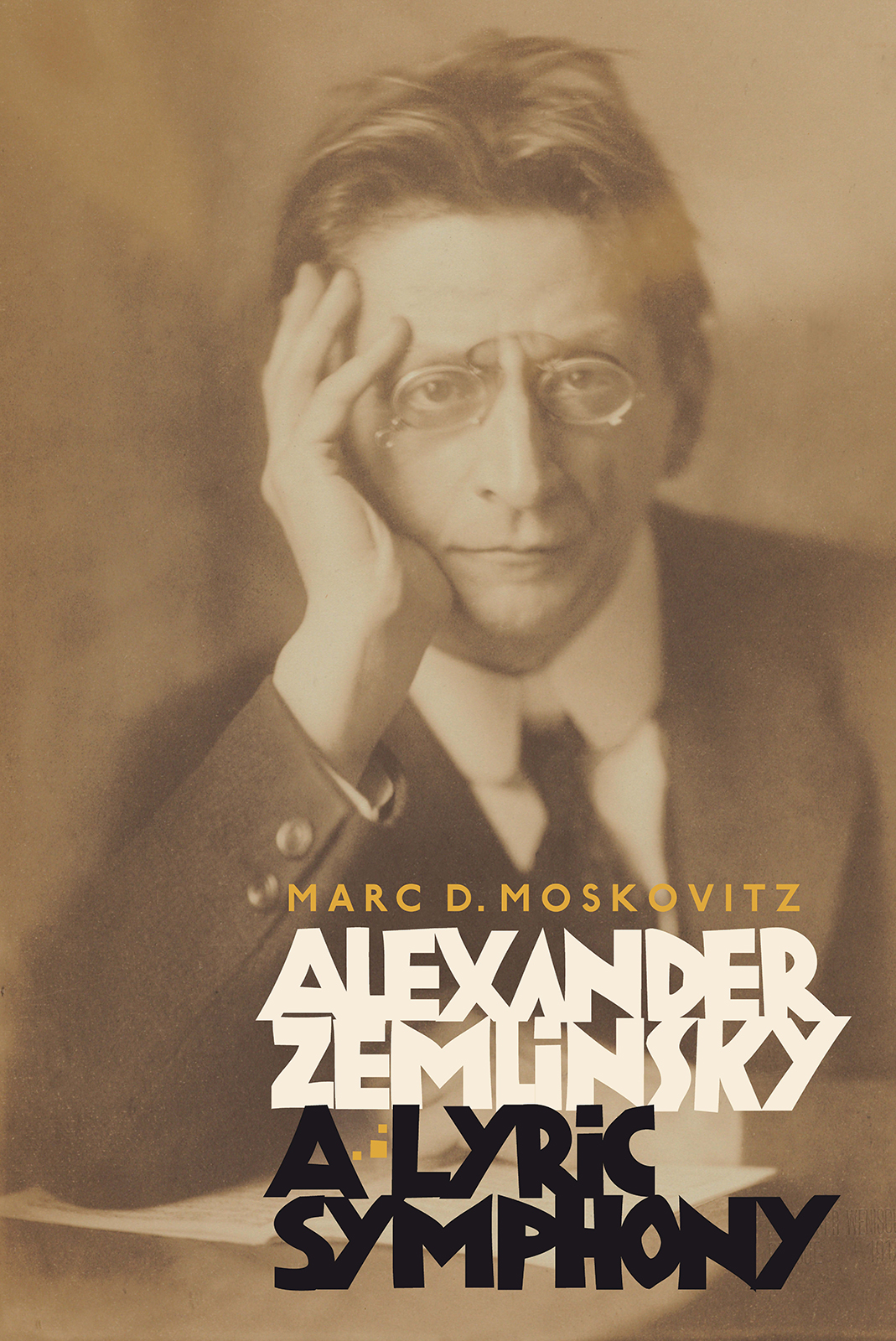

As a city steeped in music and musical tradition, Vienna was home to a variety of concert halls, opera houses and theaters, venues for both the nobility and an ever-growing, music-demanding middle class. But when the Musikverein opened its doors three years after construction began, it soon took its place among the worlds premiere cultural institutions, a result of the societys mission to promote music in all its facets. In addition to its concert halls, the Verein was also home to an historic collection of musical documents as well as the Conservatory of the Society of the Friends of Music, the Konservatorium der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. The schools prestigious faculty began attracting students from Vienna and beyond, a list that would include Gustav Mahler, Alexander Zemlinsky, Leos Janek, George Enescu and Jan Sibelius. Along with the Vereins vital concert life, the schools blossoming reputation ensured Viennas prominent role in European musical life for years to come.

Vienna was, at the same time, in a state of monumental aesthetic transition. In 1858 the Emperor ordered the citys thirteenth-century city walls to be razed and replaced with a wide boulevard lined with majestic new buildings, a showcase of Habsburg grandeur. The Ringstrasse was the result, a horseshoe-shaped avenue that skirted the inner city. No longer walled, Vienna began its slow push outwards, evident in the construction of the nearby Musikverein, although in the decades immediately following Franz Josephs decree, the most radical changes took place along the Ringstrasse itself. As ground was broken for one building after another, the Ringstrasse became framed in a potpourri of grand architectural styles the Classical Greek Parliament, the French-Renaissance-inspired Hofoper, the City Hall in the Gothic style, museums inspired by the Italian Renaissance and the Baroque-influenced Burgtheater. Palatial apartments added to the Rings allure, as did the beautiful parks, where the citys inhabitants or visitors could stroll, sip coffee, or waltz to the music of a live orchestra. Soon, trolleys were running the length of the boulevard, crisscrossing an open field that many of Viennas residents could remember having been used for military exercises. In the course of a few decades, Vienna was transformed from a medieval walled community into a modern city.

Despite the activity at its edges, much of the old city looked as it had for centuries. For hundreds of years, the Viennese had walked its serpentine cobbled streets, or Gassen , and visited the plaza known as the Graben, the city square established to mark the cessation of the devastating Black Death. Three outdoor markets traced their origins back to the thirteenth century : the Hoher Markt or High Market, the citys first fish and bread market ; the New Market or Neuer Markt , the medieval center for meat and greens ; and Am Hof , or At the Court, the sea-fish and crustacean market, which dated back to about 1280. Two of Viennas most ancient and significant structures are still standing : the imposing St. Stephans Cathedral, seat of the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Vienna, and the nearby Hofburg, the royal palace and seat of Habsburg government.

Unfortunately, despite the appearance of prosperity and stability, anti-Semitism was again on the rise in Vienna. A phenomenon that had long been associated with Vienna, anti-Semitism surfaced in many guises over the centuries, some brutal, others subtle. In one of the more extreme cases, over two hundred of Viennas Jews were publicly burned in 1421, and those who remained were herded into boats and shipped down the Danube to Hungary. But by 1867, Jews had been streaming into Vienna from the East for more than a century. In search of a better life and a modern education, Jews had been drawn to the Austrian capital ever since Joseph II passed the 1782 Toleranzpatent (Edict of Tolerance), granting Viennas mercantile Jews citizenship and numerous other rights and freedoms. Indeed, the year 1867 also brought the Dezemberverfassung , the December Constitution that accorded all Austrian citizens full emancipation. For the first time in Austrias existence, all Jews could live where they wanted, attend public schools and universities, engage in civil service, and pursue most public professions.

By the 1880s, Jews accounted for thirty-three per cent of Viennas high school and university students, and at least half of all Viennese journalists, physicians, and lawyers were Jews. Jews became prominent members of the bourgeoisie, establishing themselves in every segment of Viennese life, from philosophy, politics, medicine and science to journalism, music, education and finance. But despite Jewish success, or maybe partly because of it, anti-Semitism thrived, and Viennas Jews remained a target in times of crisis, such as the crash of Viennas stock market in 1873. Following a wave of frenzied speculation, the bourse collapsed within days of the opening of the Vienna Worlds Fair. In the weeks and months that followed, as the economy stagnated and unemployment rose, fingers were pointed at Viennas liberals and their Jewish allies. Widespread anti-Semitism ensued, paving the way for future politicians with an anti-Semitic platform men such as Georg Ritter von Schnerer and Karl Lueger.

In a city so steeped in the past, struggling with Nationalism and anti-Semitism, it is all the more remarkable that Vienna developed into a cradle of modernism at the turn of the century. In only a matter of years, Viennas cultural, intellectual and political strains converged and fashioned an entirely new city, one whose richness continues to inspire contemporary scholarship and debate even today. In light of this, a brief overview, by its very nature, cannot hope to do justice to such complex and nuanced subject matter. Nevertheless, a review of some of the periods major trends and icons may be of value, as it was precisely during this period that Zemlinsky emerged as a composer and conductor.