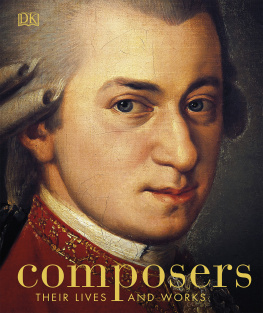

Preface

Around the year 600, the great scholar St. Isidore of Seville lamented that unless sounds are remembered by man, they perish, for they cannot be written down. In fact, the Babylonians and the Ancient Greeks had independently invented systems of musical notation more than a thousand years earlier, but after the decay of their civilizations these methods had been completely forgotten. This meant that for many centuries, the only way of preserving a musical composition was through a continuous tradition of performance, passing it on from generation to generation.

However, a century or so after St. Isidores time, monks started experimenting with ways of making a written record of the chants they sang, and in the 11th century the most important of these pioneers, Guido dArezzo, laid the basis of the system of notation we use today. This gives him such a momentous role in musical history that he features as the first subject in this book. There had been composers before Guido, but it is only after him that their works and personalities really survive.

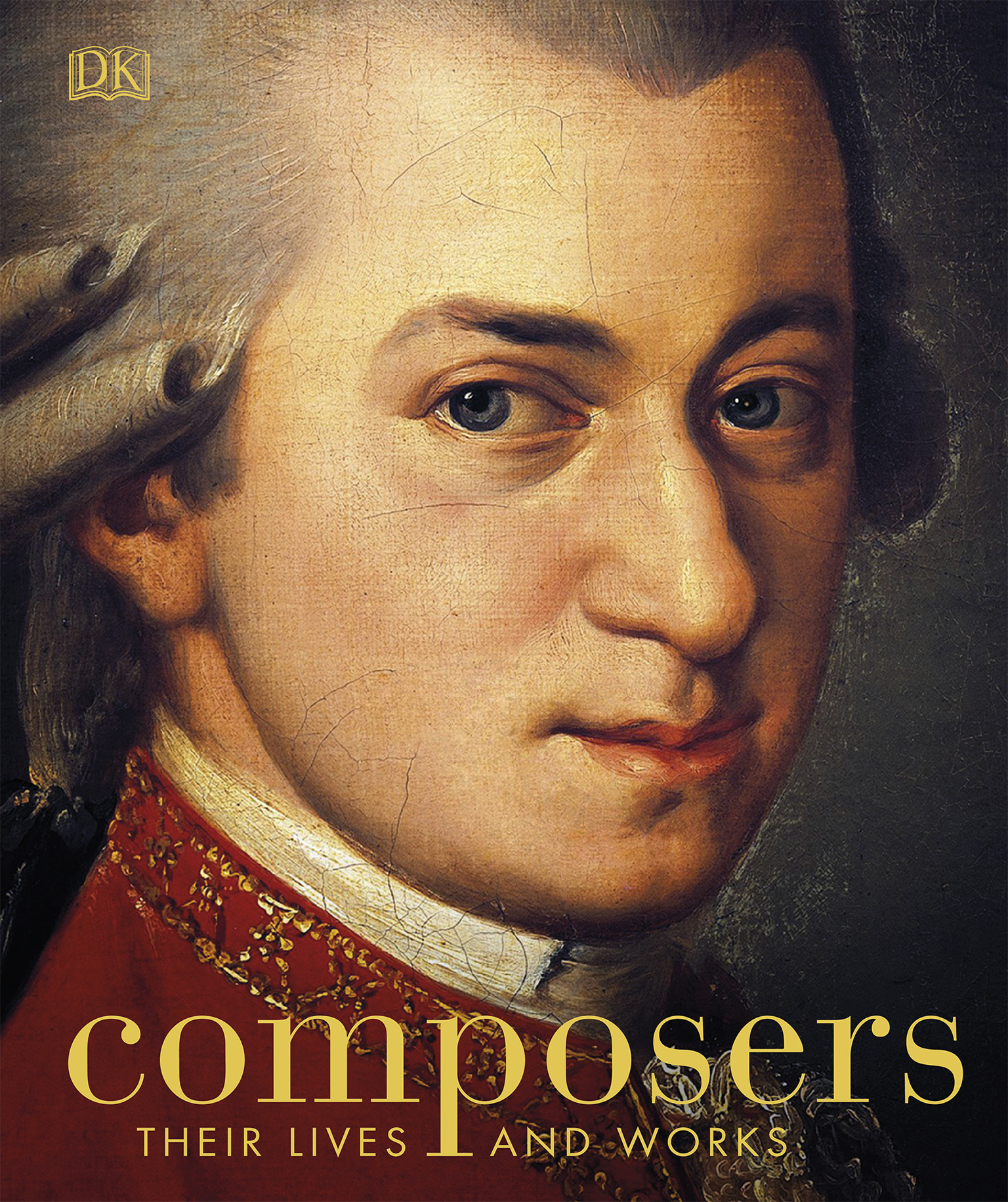

Like Guido, several of the early composers included here were Italians, and another concentration of musical genius was found in France and neighboring Flanders. England, too, had an impressive musical tradition in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 18th century, the balance of power decisively shifted, with Germany and Austria seeing a glorious sequence of illustrious composers, from Bach onward, that is unmatched anywhere else, while Vienna emerged as the undisputed musical capital of the world.

During the 19th century, the range of countries producing outstanding composers expanded greatly, with Russia, eastern Europe, and Scandinavia all coming to the fore; and from the 20th century, the distribution has become truly worldwide, with the US prominent and such diverse places as Australia, Brazil, Canada, and Japan figuring among the two dozen countries whose composers are represented in this book.

Just as the geographical spread of composers has increased enormously over the centuries, so the type of work they produce has become much more varied. In the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church was the most widespread and influential institution in the Western world; musiclike the visual artswas dominated by religion, and many leading composers devoted themselves mainly to settings of the words of the Mass, the central church ceremony commemorating the death and resurrection of Christ. However, the Renaissance brought increasing secularization to the arts, expressed in new forms such as opera, which was born in Italy around 1600, and subsequently the scope of music has expanded not only in genre but also in style and in the range of instruments and other sound sources used.

The lives of some of the earlier figures covered in this book are sparsely documented, but for many others there is a rich fund of biographical information. The popular Hollywood image of the great composer has been created largely by a handful of the giants of 19th-century music whose lives are the stuff of legend: Beethoven, the proud, rebellious outsider, increasingly isolated by deafness; Berlioz, pouring his unrequited passion for a beautiful actress into one of the most original of all symphonies; Chopin, the exquisite poet of the piano whose career was blighted by debilitating illness; Tchaikovsky, whose turbulent personal life and puzzling death continue to inspire speculation; and Wagner, whose colossal ego was matched by his colossal creative energy and originality.

Not all composers have been such memorable personalities, of course, but there are nevertheless many remarkable characters among themthe lesser-known figures as well as the household names. They include Carlo Gesualdo, the Italian nobleman who brutally murdered his wife and her lover but escaped punishment for the crime; Erik Satie, regarded as a kind of patron saint of eccentricity; and the formidable Ethel Smyth, a feminist heroine not only because she achieved success in a male-dominated world but also because she was a prominent figure in the suffragette movement and was imprisoned for her activism.

Some composers have sought solitude, but others have lived their lives on the public stagefor example, Mendelssohn, the prototype of the modern international star musician, who numbered Queen Victoria and Prince Albert among his friends. Several have been directly affected by political events: William Byrd and Thomas Tallis had to steer careful courses through the dangerous waters of the English Reformation, and both Prokofiev and Shostakovich were forced to toe the party line in Stalins repressive Soviet Union.

Some of this books subjects had lamentably short careers, notably Lili Boulanger, who suffered ill health from infancy and was only 24 when she died. The deaths of several other composers are known or believed to have been hastened by syphilis (Delius, Donizetti, Schubert, and Smetana among them), and Mussorgsky is perhaps the most famous example of a composer whose life was cut short by alcoholism. At the opposite extreme are those who ended their days at a ripe age and loaded with honors: Rodrigo and Tippett lived well into their nineties, and Saint-Sans, Stravinsky, and Verdi into their late eighties.

The varied lives and achievements of these extraordinary men and women are celebrated in this book and set within wider historical and cultural contexts. Their friendships, loves, rivalries, key influences, and working methods are all part of the stories of how they created the masterpieces that speak to us so eloquently across the centuries.

CHAPTER 1

Guido dArezzo

c. 991c. 1033, ITALIAN

While serving as a Benedictine monk, Guido developed innovative methods for learning the chants of the services, as well as a system of writing music on which modern Western notation is based.

GUIDO DAREZZO, FRESCO

This 19th-century fresco in the Chigiana Music Academy in Tuscany, Italy, shows the famous Italian monk and music theorist as an inspirational teacher.

ON TECHNIQUE

From neumes to staff notation

The numerous chants of the Catholic Church were originally learned by rote by the monks and then passed on orally. However, from around the 9th century, graphic symbols, known as neumes, began to appear above the texts to suggest the shape of the melody. In time, these were placed on a horizontal line representing a pitch, such as C or F. Guido is credited with the idea of using four lines (which were later expanded to the familiar five-line staff) to identify the precise pitch of each note.