The Composer-Performer Relationship

in Contemporary Music

By Keith Lee

Copyright 2011 Keith Lee

Smashwords Edition

Discover other titles by Keith Lee atSmashwords.com:

CoreObjective-C in 24 Hours

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

Thank you for downloading TheComposer-Performer Relationship in Contemporary Music. Althoughthis is a free book, it remains copyrighted property of the author,and may not be reproduced, copied, nor distributed for commercialand non-commercial purposes. If you enjoyed this book, pleaseencourage your friends to download their own copy atSmashwords.com, where they can also discover other works by thisauthor. Thank you for your support.

Table ofContents

The Composer-Performer Relationship inContemporary Music discusses the continually evolvingrelationship between composers and performers of Contemporary ArtMusic. The book begins with an historical overview of the roles andresponsibilities of composers and performers, from the lateRenaissance Period through the 20th Century. This overview includesa discussion of the evolution in instrumental techniques,performance practices, and musical styles during this time. Next itexamines current practices and tendencies - a key concern stressedherein is the need for composers and performers to understand theirinter-dependency and the need for a relationship that is flexible,not one-way (i.e. the composer as performer, the performer ascomposer). The book concludes with a summary of key considerationsthat both composers and performers must understand in order tofacilitate active engagement of the listener.

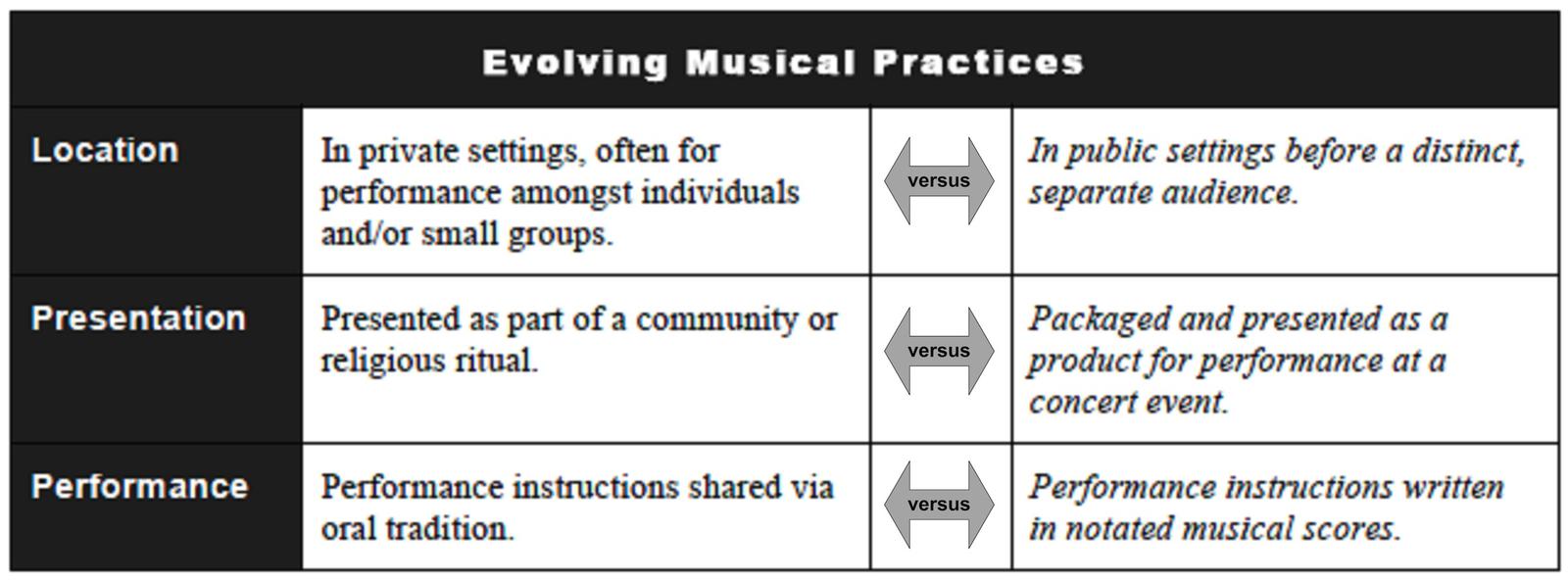

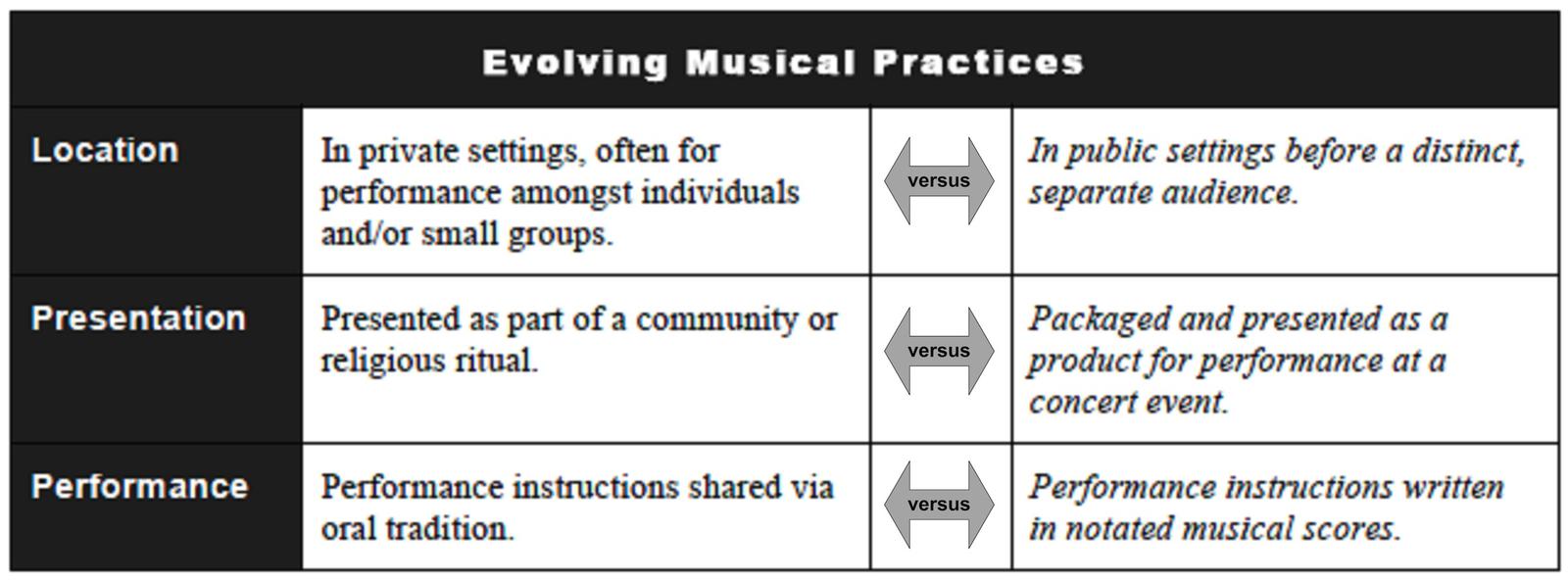

In many respects the evolution of Western artmusic reflects the evolution of our civilization from thepre-Industrial age to its present state. This is illustrated belowby the common musical genres and styles of those times, and howmusic was presented and performed.

Figure 1. Evolving Musical Practices

The Renaissance period featured multiple tuningsystems, complex polyphony, preference for consonant sounds andintervals, greater use of instruments than in previous eras (inaddition to vocal music, also writing of purely instrumentalmusic), and the adoption of musical staff notation. The inventionof the printing press was critical during this period, as thisenabled written transmission of music, and also made a greatervariety and types of music available to the general population.With music now notated and distributed (for transmission andperformance), the notion of a distinct composer for a musical work(as opposed to music shared via oral tradition, with no distinctauthor) became established. The composer typically functioned asthe performer (or one of the performers) of the work, and thecommon musical styles of this era were understood and employed byall musicians. The notated music provided flexibility forperformers to supply creative input for the sounding music, andthus the overall presentation was a shared, participative musicalexperience for composers, performers, and listeners alike. Musicduring the Renaissance period was typically performed in privatesettings, amongst a dedicated audience (particularly for secularperformances, the musicians and performers were in direct contact),and for specific occasions.

Well temperament became the common system oftuning during the Baroque period. Flexibility in the musicalcontent was provided through improvisation, use of cadenzas,multiple types of ornamentation, and other devices. Instrumentsthat continue to the present day (violin family, woodwinds, brass)began to be standardized, and composers began to write specificallyfor certain instruments in previous eras music was typicallycomposed without a specific instrumentation or orchestration inmind, and then adapted as necessary by musicians for performance.The written music of the period was harder to perform (than thatcomposed during the Renaissance), and thus required greater skillon the part of the performer. As a result of these changes theroles of composer and performer became more specified, however allpracticing musicians continued to hold both roles.

The Classical period saw a further increase inthe specification of both musical content (basso continuo writtenout, indication of instrumentation in scores) and musicalparameters (tempi indicated, general indication of dynamics,phrasing, articulations, etc., particularly for keyphrases/sections). The degree of performance freedom was thusreduced, and the performer became more of an interpreter of thewritten music rather than having creative input for the soundingmusic. Musicians began to specialize more on certain instrument(s);this was accompanied by a corresponding rise in complexinstrumental writing (for violin, harpsichord/piano, etc.). Thisincreased specialization, clearly defined instrumentation, and morecomplex writing lead to the rise of the virtuoso performer.Correspondingly, a wider separation between the composer andperformer began to be observed, as specialization becameincreasingly necessary for composition and performance of thismusic. Of course, composers continued to perform music on theirchosen instrument(s), but it became more common for composers (andperformers) to proceed separately, with performers focusingprimarily on their skills as interpreters of this music. Inaddition, as classical music became more available to the generalpopulation, music began to be presented to a wider, more separateaudience at specific (concert) events.

During the Romantic period the gap between musiccomposition and performance continued to widen. Composers assumedeven greater control of the music - all of it (including cadenzas)was now typically written-out, with little if any element ofimprovisation or spontaneity provided for the performer in thisregard. The expansion of form (thematic elements, micro/macromusical forms, key modulations, much greater use of dissonantsounds and intervals, more complex instrumentation, etc.) that wascommon during this period placed ever greater emphasis on the roleof the composer as the creator of the music, while the performerbecame almost strictly responsible for the interpretation of thecomposer's work. To some degree other musical parameters (tempi,dynamics, phrasing) came under a wider range of specification aswell (for example, composers took great pains to indicateexpression markings in their scores). Regarding presentation andoccasion for performance, music in effect became more of abusiness whose end product was consumed either through thepublic's attendance at concert events or the purchase of musicalartifacts (scores, books about music and musicians, etc.). Thedevelopment of musical training facilities (conservatories, etc.)enabled musicians to achieve ever-higher levels of skill in thechosen specialty (music composition, theory, or performance). Thedramatic increase in musical education brought a wider, moresophisticated audience, and many composers took advantage of thegreater regularity of concert life, and the greater financial andtechnical resources available. These changes brought an expansionin the sheer number of works composed, and performed. Theestablishment of conservatories and universities also createdcenters where musicians could forge stable teaching careers, ratherthan relying on their own entrepreneurship. Clear boundaries werenow present between the composer, performer, and listener;musicians typically specialized in either composition orperformance. While many composers were also performers (as had beenthe case in previous eras), the notion of the composer in theivory tower became more commonplace. However, even with thisprofusion of musical forms, expansion of musical content, andlarger instrumentation, the overall musical language (e.g. commonpractice period tonality, rhythm, and harmony) remained understoodby composers, performers, and the general public.

Next page