About the Author

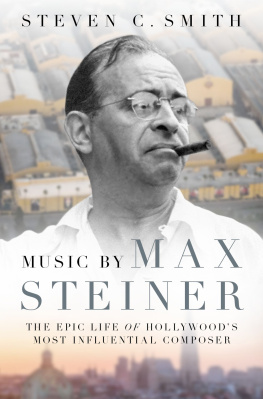

Peter Wegele is author, composer, arranger, and jazz pianist, currently living in Munich, Germany, and Sicily, Italy. He writes essays and gives lectures in Italy, Austria, and Germany about jazz and film music and about personalities such as Bill Evans, Duke Ellington, Max Steiner, and Lalo Schifrin.

Wegele is composer at Schott Music (Suite Populaire), and with his duo Necessarily Two / crossover projectbaroque meets jazz (oboe and jazz piano), he has given concerts all over Europe. He has participated in more than twenty-five CD productions in New York, Vienna and Graz, Munich, Belgrade, and Maribor, Slovenia, as bandleader, pianist, composer, and arranger. He has performed in concerts and at festivals in Germany, Austria, Slovenia, Switzerland, Finland, Serbia, Great Britain, the United States, and Italy, among others.

Together with his wife, Tatjana, Peter Wegele composes and arranges music for ZW Music Composer Studio, with assignments for theater, film, TV, and free art projects.

Acknowledgments

I express my sincerest gratitude to the following people who helped me in writing this book:

First, I thank my wife, Tatjana ivanovi-Wegele, for her loving understanding and her positive, creative energy. I can always count on her to support me and push me.

My parents, Armin and Lisa Wegele, allowed me to pursue my passion for music.

Tihomir ivanovi, my father-in-law, who passed away in July 2013, had a motto, always forward, which was a constant source of inspiration for me.

Stephen Ryan of Rowman & Littlefield believed in me and in this project.

Professor Franz Kerschbaumer of Graz offered support vital to the creation of this project and book.

The International Society for Jazz Research in Graz, Austria, sponsored my trip to Los Angeles.

And very special thanks are due to Carol Lifland and Daniel Giesberg for their hospitality and generosity when I was in Los Angeles. Another big thankyou to Carol and Daniel for proofreading my manuscript and offering so much help and advice on the English translation.

Thanks to Sanny Ziersch for making the contact with Carol and Dan.

Thanks to David Newman, composer and conductor of film music, and son of Alfred Newman, for inspiring discussions about the technique and history of film music.

Cheers to Matti Klemm, who went with me to Hollywood and was an indispensible help in finding Max Steiners star on the Walk of Fame.

And big thank-yous to James V. dArc from Brigham Young University in Utah; Noelle Carter and Jonathon Auxier from the Warner Bros. Archive, Los Angeles; Professor Wolfgang Thiel, Potsdam; Manfred Fabricius, conductor in Berlin; Dr. Eva Reinhold-Weisz, Vienna; Dr. Evelyn Deutsch-Schreiner, Graz; Sandra Tomek, organizer of the annual Max Steiner Music Award in Vienna; Professor Gerold Gruber, Vienna; Elisabeth Dechant; Johannes van Ooyen and the Bhlau Verlag, Vienna; Nizza Thobi, Munich; and, of course, Max Steiner, for his fantastic music.

APPENDIX A

Comparison of Max Steiner with Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Alfred Newman, Franz Waxman, and Hugo Friedhofer

Max Steiner was a pioneer of film music. He was an outstanding representative of his craft and one of the most prolific figures representing the classic Hollywood symphony. The 1930s and 1940s saw a number film composers of similar stature. This appendix offers four short comparisons of Steiners work to that of other highly profiled film composers of the period. Such a comparison helps us assess the composer in a historical perspective and provides valuable insight, adding to our understanding of Max Steiner.

ERICH WOLFGANG KORNGOLD (18971957)

We begin Steiners comparison with Korngold, since their biographies are similar to some extent. Both were born at the end of the nineteenth century, although Korngold was nine years Steiners junior. Both were raised and educated in Vienna, and both were considered boy wonders, protgs of Gustav Mahler. Both had notable fathers, and both managed to move their fathers to Hollywood in 1938, the year the Nazis annexed Austria.

The similarities end there, as Korngold and Steiner had very different artistic viewpoints. Steiner was raised in the world of theater and revue, whereas Korngolds father, Julius, was a respectable music critic, acquainted with composers like Johannes Brahms, Hugo Wolff, and Gustav Mahler. Steiners path to Hollywood was paved with operettas and musicals. When Korngold arrived in Los Angeles, he had a reputation as a composer of serious musicoperas and concertos. He never intended to stay in Hollywood. When Hal Wallis attempted to assign Korngold for Robin Hood, the composer replied that Robin Hood is no picture for me... I am a musician of the heart, of passions and psychology; I am not a musical illustrator for a ninety percent action picture... I cannot take the responsibility for a job which... would leave me artistically completely dissatisfied.

Steiner would never have declined an assignment in such a way. But Korngold did finally accept the job, because by 1938 the situation in Austria had become dangerous for Jews. The Nazis had banned the performance of Korngolds opera Die Kathrin, and his family lived in increasing danger. Taking the Hollywood assignment allowed Korngold to move them out of Vienna. Korngold worked in Hollywood until World War II ended and only then gave up composing for films. In 1946 he wrote, I feel that my fiftieth year is a turning point. I look back to my life and I see three periods. First, I was a prodigy, then a successful composer in Europe until Hitler, and then a movie composer. Fifty is very old for a child prodigy. I feel I have to make a decision now if I dont want to be a Hollywood composer the rest of my life.

In contrast to Korngold, Steiner was a film composer by choice. He found fulfillment in his Hollywood work and, unlike Korngold, was not a temporary expatriate. Max Steiner spoke and wrote about film music as a very distinctive musical genre.

Korngold actually composed his film scores as he would have written an opera. He described his own film music as operas without singing. The lushness of his harmonies, the sophisticated orchestrations, and a truly operatic gesture made each of his scores a masterpiece. In comparing these two composers, one has to take into consideration that Steiner had a very heavy workload while Korngold scored a mere twenty-two films. Korngolds total equaled Steiners average output every two years during the busiest period of his career. In an article published in the 1940 book Music and Dance in California, Korngold wrote that he managed to resist the demands of the film industry. He said,

I am fully aware of the fact that I seem to be working under much more favorable conditions than my Hollywood colleagues who quite often have to finish a score in a very short time and in conjunction with several other composers.

So far, I have successfully resisted the temptations of an all-year contract because, in my opinion, that would force me into factory-like mass production. I have refused to compose music for a picture in two or three weeks or in an even shorter period. I have limited myself to compositions for just two major pictures a year.

Steiner used to measure and plan his film music meticulously. Korngold worked more intuitively, noting, in the same article, that if the picture inspires me, I dont even have to measure or count the seconds or feet. If I am really inspired, I simply have luck. And my friend, the cutter, helps my luck along.

This article was one of the rare occasions in which Korngold wrote about film music.

Despite all of their differences in artistic orientation, the two composers worked on their scores in a similar way. This is likely due mostly to the studio system of the time. They both started composing after the final film edit. They both collaborated with orchestrators. Their musical vernacular was very much alike. They used leitmotifs, the tonal language of the European late Romantic period, as well as the principle of underscoring.