Table of Contents

ALSO BY GARY LACHMAN

Into the Interior: Discovering Swedenborg

The Dedalus Occult Reader: The Garden of Hermetic Dreams

A Dark Muse: A History of the Occult

In Search of P. D. Ouspensky:

The Genius in the Shadow of Gurdjieff

A Secret History of Consciousness

Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius

WRITTEN AS GARY VALENTINE

New York Rocker: My Life in the Blank Generation

with Blondie, Iggy Pop and Others, 1974-1981

For Alfred Lachman, 1924-2004, who taught me

things I am only just beginning to learn

Those who go their own way, as I do,

will certainly be subjected to many misunderstandings.

Rudolf Steiner

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people helped in the making of this book. My special thanks go to the kind people at Rudolf Steiner House, London, for the generous use of their excellent library. I am also indebted to the Rudolf Steiner Library in Ghent, New York, for answering many questions. I would like to thank Mitch Horowitz, my editor, for his enthusiasm about the project, and for the encouragement he has given both me and other writers in the field. My good friends Lisa Persky and Andy Zax were of inestimable assistance in the early stages of the work. And as always, I want to give great thanks to my sons Joshua and Maximilian, for their frequent and indispensable inspiration.

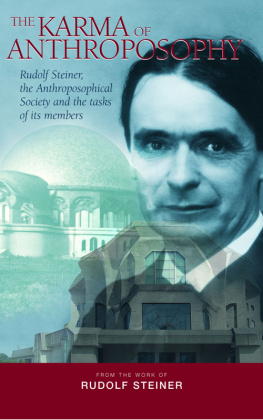

INTRODUCTION:

RUDOLF STEINERS ROSE

I first became seriously interested in Rudolf Steiners ideas in the late 1980s. I was then finishing a degree in philosophy, and supporting myself by working at a well-known New Age bookshop in Los Angeles. I had heard of Steiner before, but in a different context. I had always been interested in German Expressionism, the art and literary movement that flourished in the years before World War I, and years earlier had come across a photograph of Steiners first Goetheanum in a book on Expressionist architecture. The flowing, organic forms, the strange curves and, to me, slightly eerie shadows caught my attention, and I noted that the man who had designed and built this remarkable structure was the founder of a spiritual movement, anthroposophy, which at the time I knew absolutely nothing about and even found difficult to pronounce; Goetheanum itself was something of a jawbreaker. But a few years later, in the midst of the various fads for crystals, past lives, and the Harmonic Convergence, I decided to investigate Steiner in earnest. At the bookshop there was a well-stocked Steiner section, and standing before it I had the experience that many who are interested in learning more about Steiner have: discouragement at the sheer number of volumes. An entire bookcase and part of another were given over either to Steiners own works or to books about him. Along with the number of books, the fact that nearly all of them were published by anthroposophical publishers also raised doubts. This suggested a cult of some kind. I thought that if his books were as important as they were said to be, surely a commercial publisher would issue them; although I am open to all sorts of ideas, I have an aversion to groups or teachings that form a kind of spiritual or cultural ghetto. They also seemed weighted with a great deal of theosophical matter; and although I had read about Madame Blavatsky and found her adventures fascinating, I was less enthused about the content of her teaching.

Nevertheless, as I paged through a few volumes, I saw references to names I was very familiar with. Kant, Hegel, NietzscheSteiner had even written a book on Nietzsche. How, I wondered, could thinkers like these have anything to do with ideas about reincarnation or the astral plane? Nietzsche certainly had no patience with anything to do with higher or spiritual worlds. I also remembered that people like the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky, credited with creating the first abstract painting, had been influenced by Steiner. I decided that I would have to put aside my reservations, take a deep breath, and dive in.

I tried one of Steiners own books first, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment (since translated as How to Know Higher Worlds). Although I was studying Western philosophy, I was familiar with a great deal of occult and esoteric literature and, a few years earlier, had been involved in the Gurdjieff work. So the idea of higher consciousness wasnt unfamiliar to me, although, sad to say, I knew more about it from reading than from actual experience.

Steiners prose had an effect on me similar to that reported by earlier writers, sympathetic but critical biographers like Colin Wilson, but also convinced devotees like Friedrich Rittelmeyer. Of one of Steiners most important books, Outline of Occult Science, Rittelmeyer, who became one of Steiners closest followers, complained that if I read for any length of time, a feeling of nausea came over me. I knew how Rittelmeyer felt. To put it bluntly, I found Steiner tough going. I had read difficult books before, but this wasnt the problem. Hegel and Heidegger were notoriously difficult philosophers, but I had mastered large portions of them, and I had spent a great many months making my way through Gurdjieffs willfully obscure epic Beelzebubs Tales to His Grandson. This was different. Hegel is difficult notor not onlybecause he is a poor stylist; if that was the case, no one would bother reading him at all. Hes difficult because the thoughts he is trying to express are complex. But there was just something dull about Steiner. Nevertheless, I was bitten and was determined to assimilate at least the basics of Steiners thought.

In this I was assisted immeasurably by two books. I am a great fan of Colin Wilsons work and his little book on Steiner introduced him to me in the context of Wilsons own ideas about consciousness. Steiner purists might find Wilsons book flawed; a more recent study of Steiner refers to Wilson as someone who is sympathetic to Steiner, but unable to enter into the true meaning of his work. I can understand how a follower of Steiner might feel this, but Wilson writes as someone interested in alternative accounts of human consciousness and history, and his short study put Steiner into the context of other similar thinkers, and relates him to Wilsons own work. This was important, as it gave me a means of placing Steiner in regard to my own concerns. The other invaluable work was Robert McDermotts anthology The EssentialSteiner. That McDermott was a philosophy professor suggested that thought and ideas, rather than well-meaning but fuzzy spirituality, common to new age literature, would be important to him. His insightful introductions and linking essays made Steiners vast and complex system available to me, and they showed how Steiners ideasoften weird, strange, and downright bizarregrow out of the central themes of German Idealism and Romanticism, two areas of intellectual history I had some grounding in, not to mention much sympathy with.

Accompanied by these two guides, I persevered. It wasnt long before I recognized that I had made the right choice: Steiner was an important thinker, and it would have been a loss had I allowed my misgivings to deter me from coming to grips with him. It was clear that he had many important and fruitful insights about a wide range of subjects. To say Renaissance man sounds clichd, but in this instance its appropriate. Like his hero and mentor Goethe, Steiner was a universal man, a creative thinker who was one of the last to apply his considerable mind and remarkable intuitive powers to the whole spectrum of human experience. This kind of all-round intellect is frowned upon today, and given our climate of specialization, it isnt surprising that, even without his unusual ideas, Steiners polymath approach would have made him suspect. After finding my anthroposophical feet, I started on Steiners basic books,