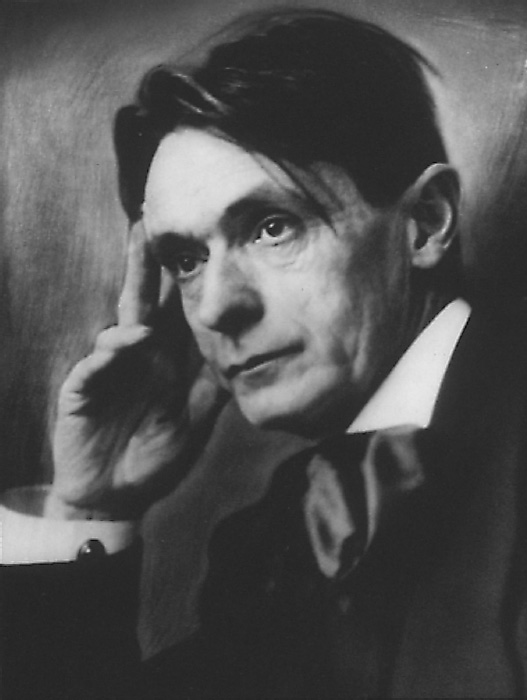

RUDOLF STEINER

An Illustrated Biography

RUDOLF STEINER

An Illustrated Biography

Johannes Hemleben

SOPHIA BOOKS

Sophia Books

Hillside House, The Square,

Forest Row, E. Sussex

RH18 5ES

www.rudolfsteinerpress.com

Published by Sophia Books 2012

An imprint of Rudolf Steiner Press

First published in English by Henry Goulden Ltd. 1975

Translated by Leo Twyman

Originally published in German by Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag 1963

Rowohlt Verlag GmbH 1963

This revised translation Rudolf Steiner Press 2000

The moral right of the author has been asserted under the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored

in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior

permission of the publishers

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 85584 285 4

Cover by Andrew Morgan Design

Typeset by DP Photosetting, Aylesbury, Bucks

Contents

PREFACE

Immortalas yet unbornonly one who understands both these states will understand eternity.

Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Steiners Autobiography, most of which he dictated from his sickbed in the last months of his life, under the title of Mein Lebensgang, has surprisingly little to say about the private side of his life. All the more care, however, does he devote to the account of the objective development of his striving for knowledge, starting from the early awakening of his interest in geometry and Copernicanism, passing on to the study of Kant, and ending with his experience of the meditative life as a fully mature man. He believed that it was presumptuous, and not to the purpose, to give an account of his private and personal experiences.

For it was my constant endeavour to present what I had to say, and what I believed I should do, in such a way as to stress objective rather than personal aspects. While I have always believed that in many fields it is the personality that most gives colour and substance to human activities, still it appears to me that this personal element must find expression in speech and action, not through the contemplation of ones own personality. Whatever may emerge from this contemplation is a matter about which an individual has to come to an understanding with himself.

Steiners reticence about his personal experience serves to bring into sharper focus the objective circumstances of his life.

* Autobiography. Chapters from the Course of my Life, Anthroposophic Press, Hudson, 2000.

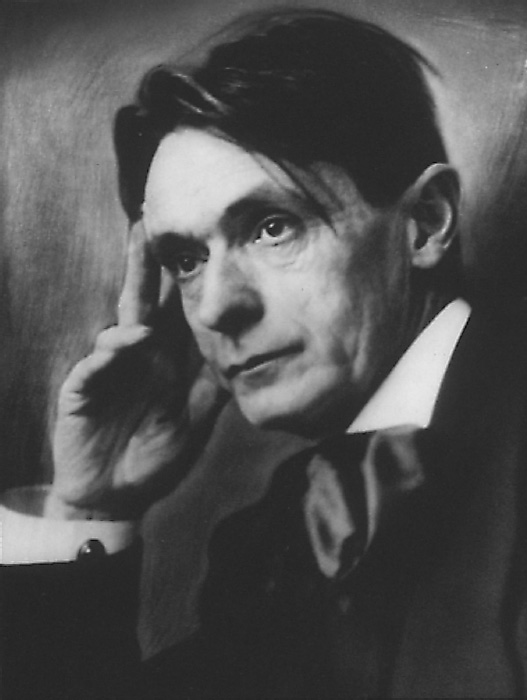

CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH

Rudolf Steiner was born at the frontier between central and eastern Europe. He himself looked upon it as something more than chance that he should have been born there. His birth to Austrian parents at Kraljevec (which is now in Croatia but was then in Hungary near its border with the Austrian empire) assumed for him symbolic significance. This east-west polarity held him in a state of tension which was to remain with him throughout his life.

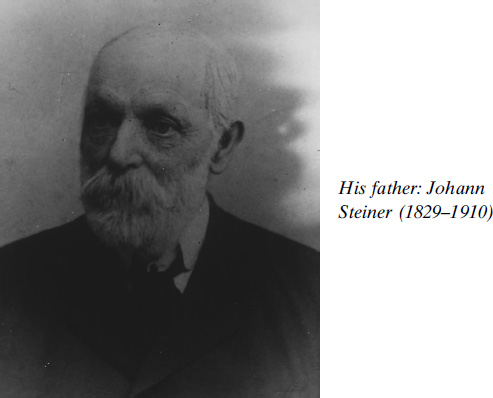

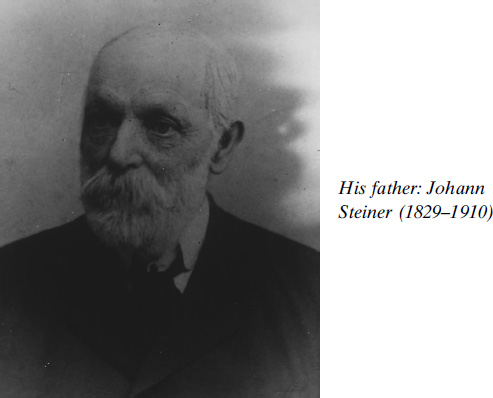

Both my father and my mother were true children of the glorious forestlands of Lower Austria, north of the Danube. Right up to our time, this remote region has remained to a great extent shielded from the destructive influences of civilization. Here his father was employed as a gamekeeper in the service of a count. The desire to establish a family led him to change his occupation.

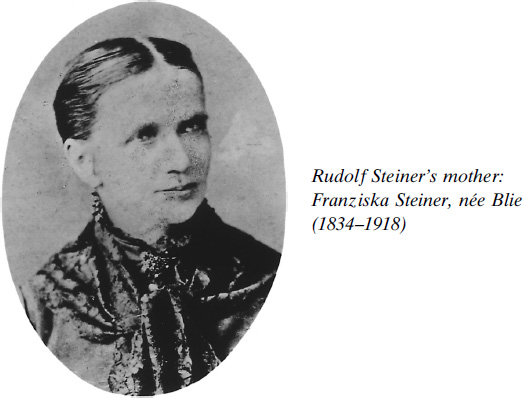

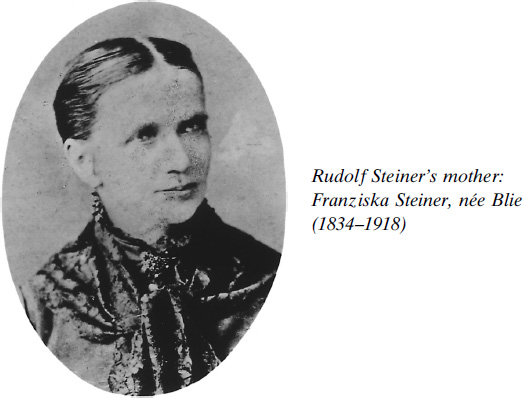

So he gave up his post as gamekeeper and became a telegraphist on the Austrian railway. His first post was at a small station in southern Styria. Next he was transferred to Kraljevec on the Hungarian-Croatian border. It was at this time that he married my mother. Her maiden name is Blie. She comes of an old-established family of Horn. I was born at Kraljevec on 27 February 1861So it comes about that my birthplace is far distant from the corner of the earth to which I rightly belong.

Two days after his birth Rudolf Steiner received Roman Catholic baptism in the neighbouring village.

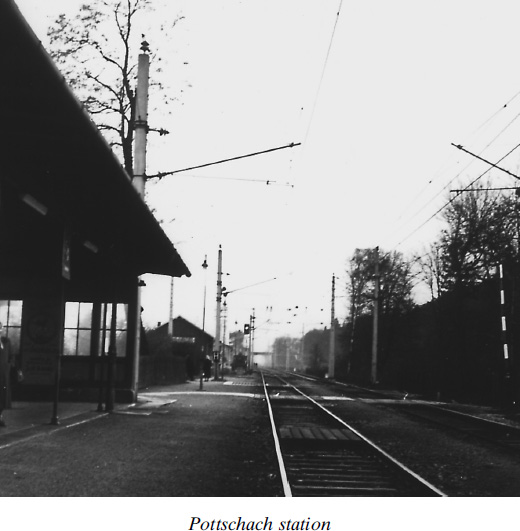

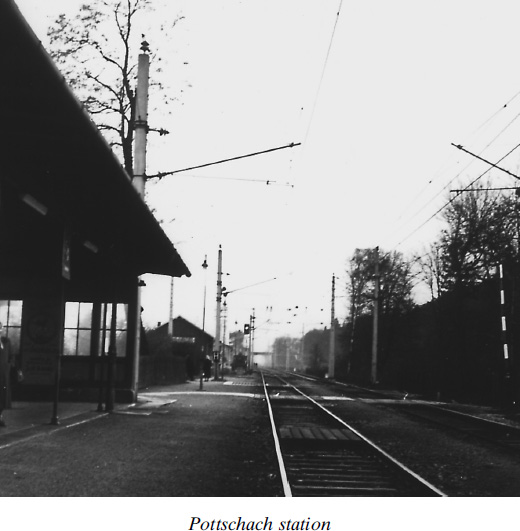

The child remained in Kraljevec for only one and a half years. After six months in Mdling near Vienna his father was transferred once more, this time to Pottschach station on the Semmering linewhich for those days was a technological marvel. This was where the boy spent his childhood from his second to his eighth year. To the end of his life Rudolf Steiner looked to that period with joy and gratitude.

The scenes amidst which I passed my childhood were marvellous. The prospect embraced the mountains linking Lower Austria with Styria: Schneeberg, Wechsel, Raxalpe, Semmering. The bald rockface of the Schneeberg caught the suns rays, which, when they were projected on to the little station on fine summer days, were the first intimation of the dawn. The grey ridge of the Wechsel made a sombre contrast.

The green prospects which welcomed the observer on every side made it seem as if the mountains were thrusting upwards of their own volition. The majestic peaks filled the distance, and the charm of nature lay all around.

In these words Rudolf Steiner describes the natural scenes that he knew in his childhood. Against this has to be set the fact that the milieu in which he grew up was largely the product of his fathers occupation. The family, to which in course of time a brother and a sister were added, lived in the station house, directly in front of which ran the railway track. The arrival and departure of the trains, the ringing of the signals, the mechanical rattle of the telegraph, created the atmosphere and divided up the day.

At that time, of course, trains were few and far between in this part of the world; but when they did come, usually there were some of the village folk who had time on their hands assembled at the station, looking for diversion in a life which otherwise they apparently found too monotonous. The schoolmaster, the parson, the steward of the estate, and often the mayor, put in an appearance.

The arrival, say, of a certain train from Vienna was the daily event that drew the leading lights together and stirred the children into activity.

It was against this background that from his earliest years the young Rudolf Steiner became aware of the polarity of nature and technology. He experienced the healing virtues of unspoilt nature, and at the same time felt the attraction of the growing power of technology.

I believe that my childhood in such an environment was an important influence on my life. For the mechanical aspects of this life engaged my interest in a compelling manner. And I am aware of how again and again these interests cast a shadow over the emotive side of my childish being, which was drawn towards nature, at once so gracious and so vast, into which, for all their enslavement to the mechanical arts, these railway trains always vanished.

Two further childhood influences were school and church, the schoolmaster and the parson. After a difference of opinion with the village schoolmaster, who it seems was none too competent, his father took on the task of educating the young Steiner.

Next page