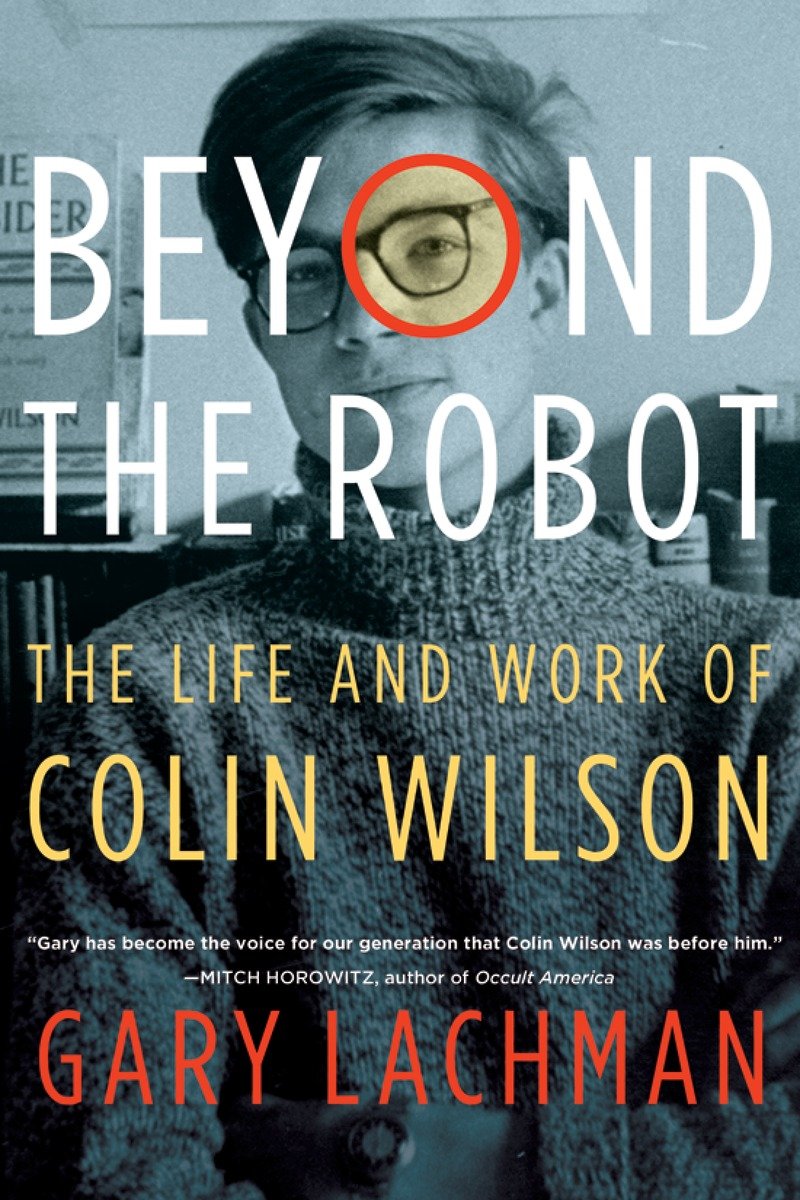

ALSO BY GARY LACHMAN

The Secret Teachers of the Western World

Revolutionaries of the Soul: Reflections on Magicians, Philosophers, and Occultists

Aleister Crowley: Magick, Rock and Roll, and the Wickedest Man in the World

The Caretakers of the Cosmos: Living Responsibly in an Unfinished World

Madame Blavatsky: The Mother of Modern Spirituality

The Quest for Hermes Trismegistus: From Ancient Egypt to the Modern World

Swedenborg: An Introduction to His Life and Ideas

Jung the Mystic: The Esoteric Dimensions of Carl Jungs Life and Teachings

The Dedalus Book of Literary Suicides: Dead Letters

Politics and the Occult: The Left, The Right, and the Radically Unseen

Rudolf Steiner: An Introduction to His Life and Work

The Dedalus Occult Reader: The Garden of Hermetic Dreams (ed.)

A Dark Muse: A History of the Occult

In Search of P. D. Ouspensky: The Genius in the Shadow of Gurdjieff

A Secret History of Consciousness

Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius

Two Essays on Colin Wilson

AS GARY VALENTINE:

New York Rocker: My Life in the Blank Generation with Blondie, Iggy Pop, and Others, 19741981

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2016 by Gary Lachman

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Tarcher and Perigee are registered trademarks, and the colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

eBook ISBN 9780698184312

Cover design by Tom McKeveny

Version_1

To Outsiders everywhere

Reality is not what happens to be most real to us at the moment. It is what we perceive in our moments of greatest intensity.

Colin Wilson, The Craft of the Novel

My lifes task is to light a fire with damp sticks. The drizzle falls incessantly. Yet I feel that if only I could really get the blaze started, it would become so large and fierce that nothing could stop it.

Colin Wilson, Phenomenological Journal, January 31, 1965

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A PILGRIMAGE TO TETHERDOWN

I n the summer of 1983 I found myself traveling to Cornwall, in the far west of England. For the past several years I had been reading the work of a writer whose ideas interested me deeply and I was on my way to meet him. His name was Colin Wilson.

Wilson had achieved overnight fame in 1956 at the age of twenty-four with his first book, The Outsider, a study in existentialism, alienation, and extreme mental states. No one was more astonished than Wilson himself to discover that this work dealing with the angst and spiritual crises of figures such as Nietzsche, van Gogh, Dostoyevsky, T. E. Lawrence, H. G. Wells, and others had become an instant best seller. But surprisingly it had. Reviews were glowing and critics tripped over each other to hail Englands own home-grown existentialist. After years of struggle, sacrifice and hard work, Wilson had made it. The Outsider was in.

The glory, alas, was short-lived. Fame, especially in England, is fickle, and after the initial praise A MAJO R WRITER, AND HES ON LY TWENTY-FOUR, the headline of one review ranthe press and serious critics soon turned on what they were now calling a messiah of the milk bars. The tag came from Wilsons association with a group of writers the press had christened the Angry Young Menroughly equivalent to Americas Beat Generationpeople like John Osborne, Kingsley Amis, John Braine, and others. Although Wilson had very little in common with them, he was guilty by association, and when the critical tide turned against these angry men, he was caught up in it. In practically no time at all, Wilson went from being a boy genius to persona non grata, a status among the literary establishment that he labored against for the rest of his career and was never quite able to throw off.

It was after this critical thrashing that Wilson left London and moved to a remote village in Cornwall. Here he hunkered down and over the years developed what he called a new existentialism, an evolutionary, optimistic philosophy which would eventually include areas of the occult and mysticism. He hoped this would counter the bleak dead end in which he believed the existentialism of Sartre, Camus, and Heidegger had found itself, and in which most of modern culture had also become mired.

Wilsons idea of an optimistic, evolutionary existentialism excited me. I had spent the past several years tracking his books down, reading everything by him that I could find. That was why I found myself at the tail end of a two-month sojourn in Europemuch of it spent visiting sacred sitesmaking the journey down to Cornwall to meet him.

I had first come across Wilsons work some years earlier, in 1975, when I was nineteen and living on New Yorks Bowery, playing in the band Blondie. I had recently developed an interest in the occult. Punk was on the rise but remnants of the previous hippie generation could still be found, and among the books I read at the time was Wilsons The Occult, which had been published in 1971 and which briefly reestablished his reputation after the critical bashing following The Outsider.

What was exciting about The Occult was that Wilson approached the mystical, magical, and paranormal from the perspective of existential philosophy. It was not a book of spells or accounts of haunted houses but an attempt to understand occult phenomena in terms of a philosophy of consciousness that Wilson had been developing for more than a decade and which I later understood was based on the work of the German philosopher Edmund Husserl, whose phenomenology became the basis for existentialism.

Explanations of phenomenology and its importance for Wilson and for human consciousness in general will be found in the pages that follow. Here I will say that the essence of Husserls philosophy, and the aspect of it that made the most impact on Wilson, was what he called intentionality. Simply put, this is the recognition that consciousness does not passively reflect the world as a mirror does, which had been the standard idea of consciousness since the philosopher Ren Descartes established it in the seventeenth century. Instead it actively reaches out and grabs italthough we, for the most part, are unaware of this activity. Consciousness, then, for Husserl, is not a mirror but a kind of hand. And while a mirror reflects what is in front of it whether it wants to or notit has no choice in the matterour hands, we know, can have a strong grasp or a weak one or, in fact, none at all.

It was something along these lines that Wilson tried to get across to me when I finally arrived at his home, called Tetherdown, near the small fishing village of Gorran Haven, on a scorching July day. I had called him from a phone box in Penzance, where I was staying. He was friendly and immediately invited me to come and stay the night; he even offered to pick me up at the train station in St. Austell, the nearest one.