Having spent seven years as a classroom teacher and twenty-two years at the National Army Museum in Chelsea, I estimate that I have taught more than half a million young people about the Western Front in the Great War. In that time, I have tried to describe the routine of trench life, rather than simply barrages, going over the top and endless war poetry. Sadly, the nature of the curriculum and the focus of interest has always been the day of battle rather than the ordinary tour in the frontline. My grandfather served between 1916 and 1918. In this time he was involved in the closing days of the Battle of the Somme, was in reserve during the Battle of Arras, in the frontline for the major German attack of spring 1918 and was in action during the Allied 100 Days offensive. During that time, he was in action for no more than a few days, was wounded three times and came home once, wounded. By far the majority of his time was spent alternating between weeks in the line, in reserve and resting. An account of his career, which focused on his few days in battle, may emphasise what we find interesting today, but it is not typical of his experience or that of his comrades.

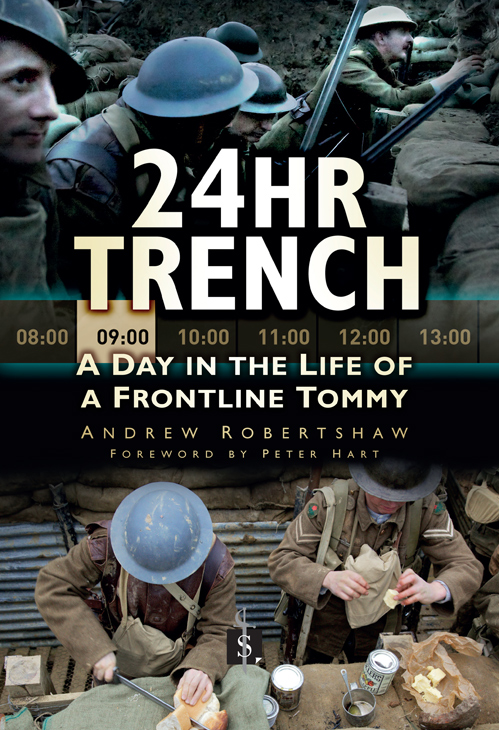

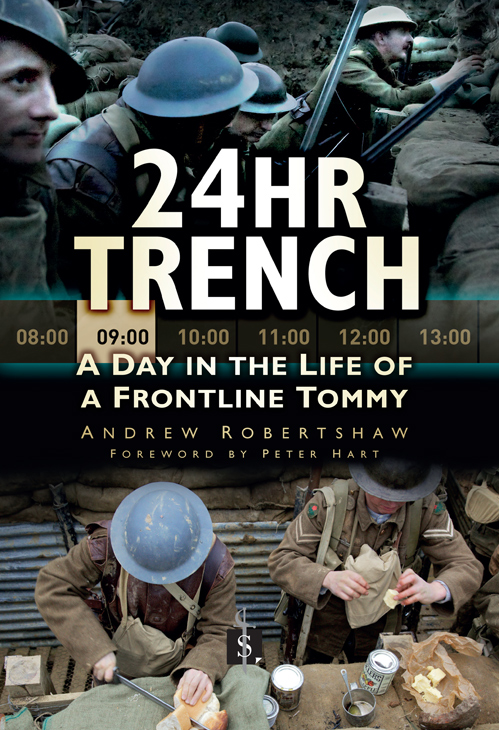

One early idea I had with the 24-Hour Trench concept was to use a replica trench in a museum as a backdrop on to which an audio-visual display could be projected. The plan would be to speed up reality to compress the typical trench day into something that a museum audience would be happy to watch. However, every time the project was discussed in a gallery planning group, someone would suggest just adding in some shellfire, a gas attack or a trench raid to make the experience more typical. My response that this would, if anything, make the whole thing less typical was ignored and the project was quietly abandoned. This resulted in my decision to turn the project into a book covering just 24 hours in a real trench, in a real location at some point in the war. The advantage of a book is that I had complete control of the content and that the readers could take their time to absorb the detail. In addition, by being based on real events, it would not simply be another typical book about the Great War.

To make the book as accurate as possible required a great deal of research and I was very fortunate that my colleague Steve Roberts was able to use his time at the National Archives, Kew, to look at various war diaries for units relevant to my chosen sector of the line Hooge near Ypres. One disappointment for me as a Yorkshireman was the discovery that the most appropriate division in the line was recruited in Lancashire. However, historical accuracy forbade me from tinkering with the facts. The period in which the division held the line between Wieltje to Railway Wood in the spring of 1917 is described in the divisional history as follows:

During the first few months the sector was might be called a quiet sector. Both the enemy and ourselves were tired after the strenuous work of the Somme and required, and obtained, rest.

The Story of the 55th (West Lancashire) Division ,

Rev. J.O. Coop, Liverpool, 1919, p. 46

By being strictly authentic, I was also able to make a key point about the experience of the frontline. One battalion of around 800 men in the division in question suffered two casualties during their tour of frontline duty. One man suffered head injuries when he fell down a well in the dark and another cut himself so badly on corrugated iron that he was medically evacuated and the nature of his injury mentioned in the War Diary. In other words, during nearly four days of frontline service in one of the most disputed areas of the British-held sector of the Western Front despite shelling, snipers, machine guns and mortars, no one was injured sufficiently badly by enemy fire to be treated for their wounds. In the same period, no one was killed! It would always be possible to argue that this was exceptional, the evidence indicates otherwise, but the key fact is that this is what happened. This meant that I felt confident that I could take one day out of a tour of duty in the frontline for an infantry unit, show the full routine in the 24 hours and miss out heavy shelling, mass casualties or any other clich of movies and still be historically accurate.

The final question was how many men to portray as my typical unit. By 1917, a platoon of around thirty-six soldiers was the main tactical sub-unit of the British Army. I was daunted by the feeding and housing of this number of soldiers even if they were all volunteers and was aware that I would need rather more trench to house them than I had space to build. The solution was to represent the smallest sub-unit The Section. This consisted of ten or a dozen men and there were four within each platoon. According to the pencilled additions to my copy of the Training Manual S.S.143, Instruction for The Training of Platoons For Offensive Action, 1917 , No.1 Section was equipped with one or more Lewis machine guns, No.2 Section consisted of bombers armed with rifles but trained to throw hand grenades and No.4 Section was armed with rifles equipped with dischargers that could fire grenades to long distance. These were all specialists. The most ordinary section was No.3, the riflemen. This is not quite correct, as the men in this section were the best shots, snipers and bayonet fighters. However, to make my section representative of the ordinary soldier it was ideal. All I had to do was to take just over a dozen volunteers, clothe, equip and arm them historically accurately for 1917, then put them in a replica trench system under conditions as close to the real experience as possible for just over 24 hours so they could be photographed. When I first thought about the idea, it did seem ambitious. It did not get easier.

The 24hr Trench project involved a very large number of people many of whom never saw the finished trench system, as they were not there for the weekend event and photography. I am immensely grateful for their assistance, advice and, in some cases, sweat, blood and tears. Corporal S. Haines and men of 23rd Regiment Royal Logistic Corps from St Davids Barracks near Bicester carried out the basic work on the trench. Teams of various sizes made up from the following volunteers carried out the rest of the work: Martin Stiles, Steve Roberts, Lesley Wood, Anthony Roberts, Ian Wedge, Mark Khan, Pete Birkett, Max Birkett, Steve Wisdom and Dr David Kenyon. Many of the same people also provided the back-up team for the photography and some spent the night under the stars. The cook for the weekend was Diane Carpenter. There can have been few places on the Western Front in the Great War where the menu included both a vegetarian and vegan option!

The soldiers in the trench were Neil McGurk, Stephen Wisdom, Jonathan Keeling, Paul Harding, Mark Griffin (who also provided the special effects), Pete Birkett, Max Birkett, Ian Wedge, Richard Townsley, Alex Sotheran, Justin Russell, Vince Scopes, Lewis Scopes and Richard Bass. The German sniper was Martin Stiles.

Richard Ingram was a behind the scenes influence providing a great deal of useful advice and a few items required for the trench. Another office-based contributor was Natalie Hill who in between work as a volunteer at the Royal Logistic Corps Museum typed text, emailed images and taught me how to use Dropbox. The sniper items used were provided by Dr Roger Payne. I am immensely grateful for his support in adding a little more very expensive detail to the project.

Phil Erswell who runs PaGe Images took the majority of the photographs. He found himself pitched into 1917 and ended up conducting his longest and coldest shoot in changing light conditions whilst trying to avoid catching glimpses of the twenty-first century. Without his imagination and skill, the whole project could have been a failure.

Next page