Tommy: a British infantryman pictured in c.1916. He carries full marching equipment, webbing, Short, Magazine, Lee Enfield (SMLE) rifle, PH helmet gas mask in its haversack and steel helmet. A member of a pioneer battalion, he would have been expected to both fight and dig on the Western Front

For all who served in Fred Karnos Army

We are Fred Karnos Army

The ragtime infantry

We cannot march, we cannot shoot,

What bloody use are we?

And when we get to Berlin

The Kaiser he will say

Hoch! Hoch! Mein Gott,

What a bloody fine lot

Fred Karnos infantry

CONTENTS

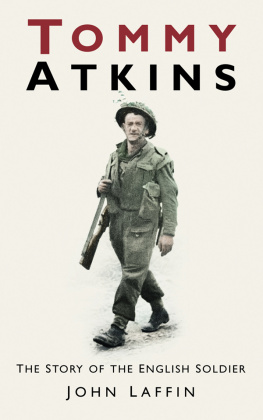

Tommy Atkins was the name first given to the British soldier by Wellington, but which stuck with him through two world wars. It had common currency on both sides of the line, Tommy of the popular press becoming Tommee shouted from the German lines. First appearing in official literature in 1815 (when it was used in War Office Orders and Regulations ), the name also had a place a century later in the soldiers pay book of the Great War. Though the British soldier of 191418 saw himself as a member of Fred Karnos Army, an army of largely amateur soldiers more often than not muddling through the war, it is the name Tommy that stuck. This familiar title became much more than a shorthand for the British soldier; it became imbued with concepts of unremitting stoicism, of phlegm and grim humour in the face of the extreme conditions of warfare. In more cynical times, these concepts might be fairly challenged, but the written word of the time, the letters, diaries and memoirs, all attest to its validity. And with the conditions of trench warfare so trying, it is now difficult for us to comprehend how they managed it. With all former combatants of that terrible war now gone, seeking out a means of understanding what it was like to serve requires us to delve into archives, to trawl through letters and diaries, and to listen to the recorded words, fortunately captured by the nations museums before it was too late.

A soldiers memories

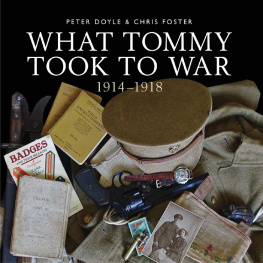

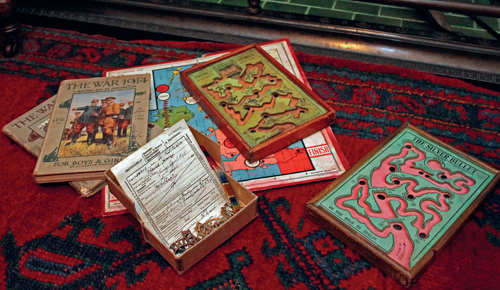

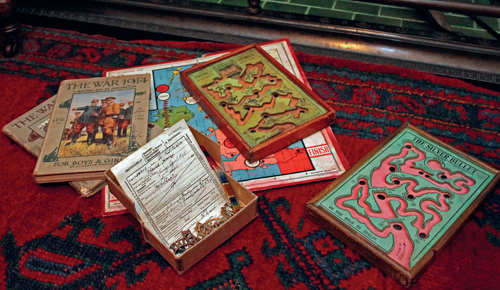

What did you do in the war, Daddy? A childs mementoes of the war

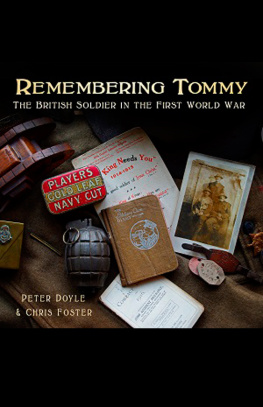

And then there are the numerous artefacts, mostly everyday objects that might have been carried in the pack or pocket, or that might have sat on the table, draped an armchair or carried into the frontline. Often these were retained by a soldier because of an association with a time or place a piece of trench art, a lighter used regularly, a uniform jacket hung in a wardrobe, a pay book kept as evidence of service or sometimes they were preserved by chance, sat in a drawer or gathered in a forgotten corner. Each one has a hidden story, and each one provides the key to interpreting just a little of what was going on around the men and women of that war. And if each object has a story, then assembling them in context might assist us in our quest to understand just a bit more of what it was like to serve in this most significant period of history. As such, this book is a remembrance of Tommy Atkins, using the objects he might have carried, used and lived with throughout the four years of war. Soldiers are mostly absent from our pictures; the grouping of the artefacts and the situations they are placed in are there to stimulate the mind of the observer.

Our focus is both life at home and on the Western Front. Arguably, the Western Front was the most significant theatre of war, as it was here that the principal foe, Germany, would have to be beaten. Though at the time generals and politicians divided into opposing camps of westerners and easterners argued about the wisdom of either committing more men to the fields of northern Europe or opening and sustaining fronts (the so-called sideshows) in the Middle East and Balkans, it was France and Flanders that saw most of the British soldier.

On the Western Front, the British soldier expended prodigious efforts facing a determined enemy an enemy equally determined to sit on the defensive in positions that represented the westernmost extent of a Greater Germany. Strong, and getting stronger, these entrenched positions were an inevitable consequence of the power of modern warfare, with artillery and the machine gun exacting a terrible price from attacking troops. The term Western Front was borrowed from the Germans, who were fighting a war in both the east and west. It was here that a war of position developed in the winter of 1914, when the options for turning the flanks of the German armies advancing across France and Belgium like a swinging door had been exhausted. From the moment that trenches had been dug it was inevitable that the war would descend into a war of trench lines and subterranean battles (as it had done in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904). Stretching from the Swiss frontier to the North Sea, these lines were inhabited by Allies from France, the British Empire and Belgium (ultimately joined in 191718 by the USA and the Portuguese). Though the British Army would take up a fraction of the whole line, its positions were an essential part of the Allied frontline throughout the war, with an increasing burden of responsibility as the war progressed. In the west, the Allied lines would be stretched in the face of offensives, yet they remained intact until 1918, when first the Germans, and then the Allies, were to break out of their positions, finally resuming open warfare in August 1918.

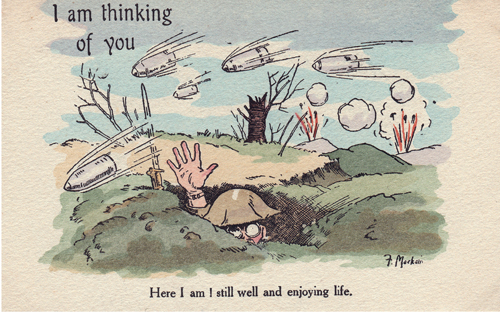

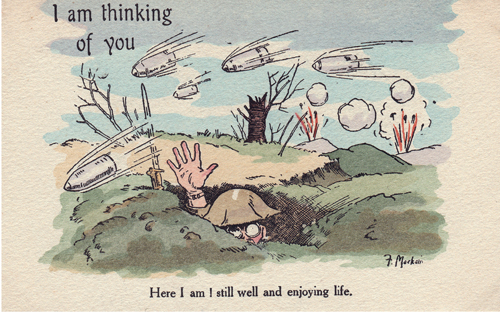

This book, then, takes a journey from the joining of the soldier through his tours of the trenches to his visits home where domestic life on the home front carried on in the face of growing shortages and the threat of aerial attack. For space, it focuses on the period that encompasses the height of trench warfare, from early 1915 to late 1917, when life for the British soldier was dominated by a cycle of in the linein reservesin rest, each part composed of four to eight days on average. It is the infantryman who appears most in this book, as it was the infantryman who most experienced trench warfare during the war. But we cannot forget the large numbers of men who served the guns, who engineered the battlefield, and who supported the frontline soldiers. As such, the men of the artillery, engineers, Army Service Corps (ASC) and Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) also appear. In illustrating life at the front, we can only hint at the filth and degradation of the trenches, and cannot demonstrate fear, pain and suffering and loss but the purpose of our book is to capture something of the atmosphere of the period. With objects mute witnesses to the events of wartime, placing them back in to context provides a key, unlocking just a fraction of the past. Our focus is on the routine of daily life; the unremarkable rather than the dramatic. The images allow observers to draw their own conclusions, and to conjure their own memories of family stories, of personal memoirs, of books read. In spirit, Remembering Tommy follows the rhythm illustrated by Pte Fergus Mackain, who, in a series of postcards, gave one of the most accurate depictions of the life of the average Tommy in existence.

Next page