To Lizzie, Jessica and Corinna, the women in my life

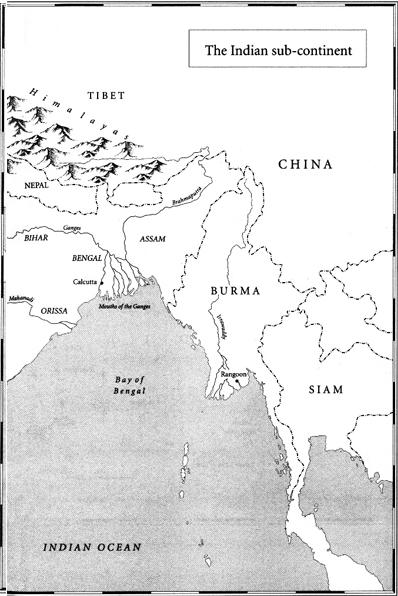

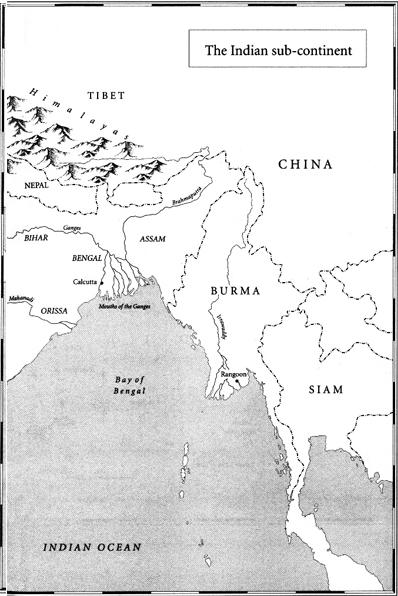

The Indian sub-continent

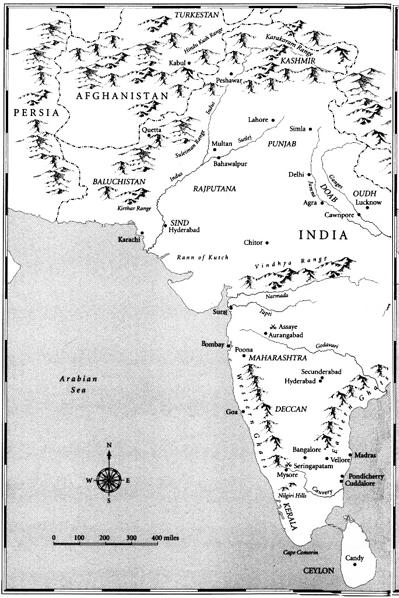

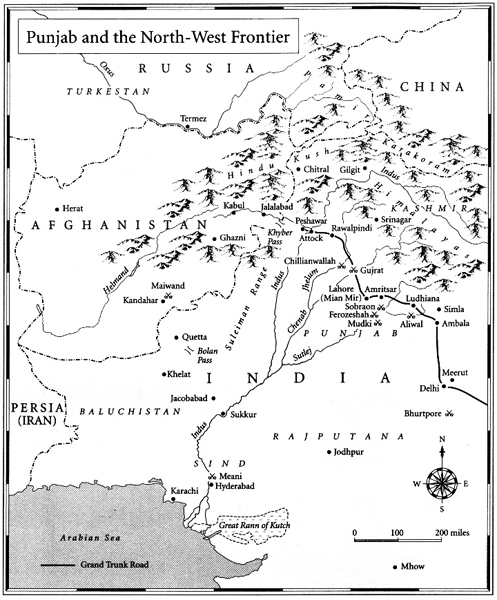

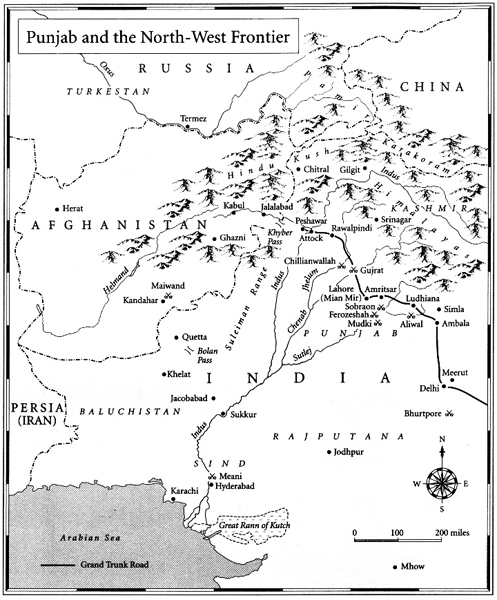

Punjab and the North-West Frontier

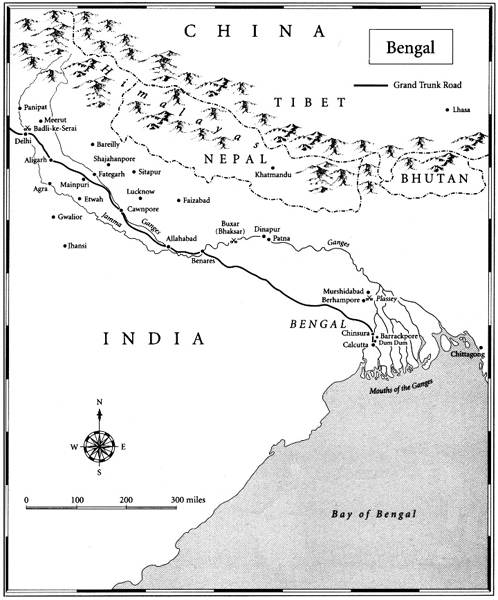

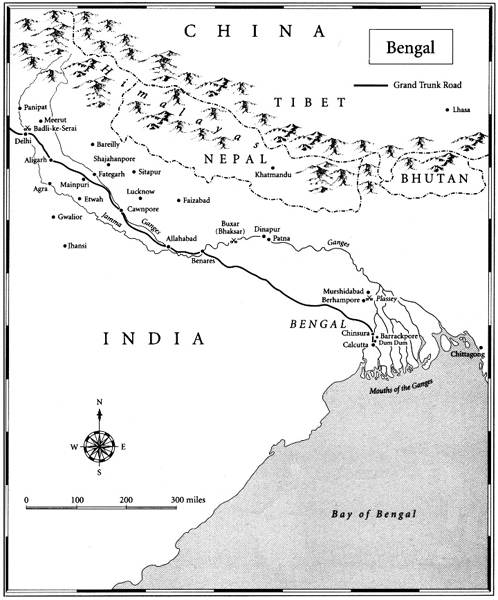

Bengal

Riding through the densely packed bazaars of Bareilly City on Judy, my mare, passing village temples, cantering across the magical plains that stretched away to the Himalayas, I shivered at the millions and immensities and secrecies of India. I liked to finish my day at the club, in a world whose limits were known and where people answered my beck. An incandescent lamp coughed its light over shrivelled grass and dusty shrubbery; in its circle of illumination exiled heads were bent over English newspapers, their thoughts far away, but close to mine. Outside, people prayed and plotted and mated and died on a scale unimaginable and uncomfortable. We English were a caste. White overlords or whiter monkeys it was all the same. The Brahmins made a circle within which they cooked their food. So did we. We were a caste: pariahs to them, princes in our own estimation.

F. YEATS-BROWN, Bengal Lancer

Like it or not, the British conquest and dominion of India is one of historys great epics. A vast, populous and geographically varied continent half a world away from these islands was dominated for over 300 years by a relatively small number of British. It is no exaggeration to say that India was indeed the jewel in the crown of the Empire, with a unique place in public and official estimation in general and in the history of the British army in particular. The British conquered India by military force, proclaimed the distinguished Indian civil servant Sir Penderel Moon, and the campaigns and battles by which this was achieved were historical events without which Britains Indian empire would never have come into existence.

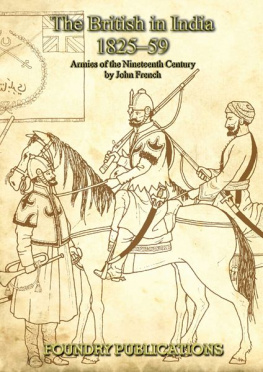

It is remarkable to see how much was accomplished by so few. When Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837, the European population living in India numbered around 41,000, about 37,000 of whom were soldiers; another 1,000 worked for the Indian Civil Service and about another 30,000 of the population was of racially mixed parentage. There was a native population of at least 15 million, less than 200,000 of whom served in the army of the Honourable East India Company, the commercial corporation which, in what is perhaps the most striking example of the flag following trade, actually ran the subcontinent until the British government assumed its responsibilities in 1858.

Historians are unsure whether British rule was a good thing or a bad thing, with two real heavyweights in the debate having disputed the matter recently. In Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order, Niall Ferguson declared that: The question is not whether British imperialism was without blemish. It was not. The question is whether there could have been a less bloody path to modernity. His answer is generally negative, arguing that the Empire brought free markets, the rule of law and relatively incorrupt government.

And so this is neither a book about the rights or wrongs of the Indian Empire, nor a history of its rise and fall (for the latter Lawrence Jamess Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India stands pre-eminent as a readable popular survey). Instead, I seek to illuminate the central paradox of the Raj: how did a relatively small number of British soldiers gain and retain control of the subcontinent? What encouraged them to go to India; what did they make of an environment so very different to their own; how did they live there and, no less to the point, how did they die?

I have chosen to start my narrative proper in 1750, just before the first major battles which gave the British control of Bengal, and on the eve of the arrival in India of large formed bodies of British infantry. I have selected 1914 as my cut-off date for a variety of reasons. While dates rarely mark abrupt historical watersheds (and in many ways the India of 1920 had very much in common with the India of 1910), the experience of the First World War marked British and Indian soldiers alike; the Indianisation of the Indian army was fast becoming a major military policy issue; and popular historiography, its trail blazed by Charles Allens Plain Tales from the Raj, is at its strongest for the period 191447. Much as I would like to consider the experience of the British soldier in India over this latter period, this is not the book in which to do it.

The title sahib could be casually granted or hard won. Civil servant Walter Lawrence had to supervise the hanging of a burly, wild-looking Pathan who had confessed to murder but maintained that his young accomplice was innocent. Lawrence tried to get the youngsters sentence reduced, but failed. I do not think you are faithless, said the Pathan, and I will make one more appeal to you. I am kotwal [a policeman or magistrate] in my village, and my enemies will ask the government to sequestrate my land, and my daughter will be landless and lost. Lawrence was able to ensure that the daughter would inherit, and on the day of the hanging he saw a pretty girl of about fourteen years, who made a graceful obeisance of farewell to her father and of thanks to me. He was a sahib again.

The word sahib went even farther. The common suffix log (meaning people) was used to produce baba-log for children, bandar-log for the monkeys in Kiplings Jungle Book or the insulting budmash-log for ruffians or villains (shaitan-log the devils people, was even worse, so bad that a distinguished relative of mine thought it applicable to successive governments), and gave sahib-log, which might also be used to describe European gentry. This was a more polite word than gora-log, used to mean Europeans in general or, as Yule and Burnell would have it, any European who is not a sahib. The prefix mem gave memsahib, the term for a European lady, although as late as the 1880s this was generally used only in the Bengal presidency. Madam Sahib was the Bombay version, and doresani, from doray, the South Indian equivalent of sahib, was popular in Madras.

For the purposes of this book sahib is used in its broadest sense to mean all British soldiers serving in India, from sahib-log of the most refined sort, to gora-log, red of face and coat, intent on mischief in the bazaar. This account is firmly based on their own writings, in the form of letters home and diaries a respectable stream of which is preserved in the Oriental and India Office Collections of the British Library and the National Army Museum. As far as printed sources are concerned, in addition to examining such well-known accounts as Frederick Robertss Forty-One Years in India and Garnet Wolseleys The Story of a Soldiers Life, I was able, thanks largely to that wonderful repository of the long-forgotten, the Prince Consort Library in Aldershot, to use far scarcer memoirs such as W. G. Osbornes The Court and Camp of Runjeet Singh and James Woods Gunner at Large. There are fewer accounts here by private soldiers and NCOs than I would have wished, but Privates Waterfield and Ryder carry their muskets with HMs 32nd Foot, and Sergeant John Pearman plies his sabre with HMs 3rd Light Dragoons. I have also included the experiences of the mens families the women who followed them from camp to camp, bore their children, nursed them as they died, and all too often died themselves. The inimitable John Shipp, twice commissioned from the ranks, makes his appearance, and that staunch freemason, Sergeant Major George Carter, tells of life in 2nd Bengal Fusiliers. We also have Subadar Sita Ram who served with a regiment of the Bengal Native Infantry in the first half of the nineteenth century on hand to give us his own view of the British army in India:

Next page