R ICHARD HOLMES WAS a professional in several fields. As an author he never failed to fulfil a contract, so it is ironic and tragic for his many readers that an untimely death prevented him from completing the final touches of this his last book. However, we are lucky that he left it in such good shape that only the odd addition has had to be made. This was typical of the man whose sense of duty meant that he always did what he promised. The trouble was that he frequently promised too much.

I was an unlikely friend to Richard Holmes, he an academic and I with not an A level to my name. It was a chance remark and a question that led us to be companions astride our horses, first in France and then in other parts of the world. Our love of the horse and history forged a friendship which coped with late nights, hangovers, and a good deal of snoring. To spend weeks on end in the company of this extraordinarily well-informed man was to me a great joy. On those days the modern world was far away, and only occasionally did outside communication interrupt our imagining of another age and another battle. Reading the pages of this book, I felt increasingly that he was beside me at the camp fire, enjoying a mug of local liquor, telling one more anecdote, one more yarn. On those trips we were a happy band; Richards repartee and amusing turn of phrase were an important part of the expedition even when things went wrong we have a bijou problemette. Where there was Richard, there were also smiles and laughter.

Richard played many roles in his life but soldiering was at the heart of it. From those early days when he joined the Territorial Army and when he studied the Franco-Prussian War at university, he had a fascination for the history of warfare but then so do many others. He was unusual in that his power of recall was quite extraordinary in its breadth and detail. While on a tour of a World War One battlefield, he stayed at a French noblemans house. After the introductions, he remarked in his particular style of French, that it was a pleasure to meet the descendants of a family who had fought against the English at Crcy. The family were astonished at his knowledge of French history, and could not do enough for him and his companions. His other notable quality was the way he made his subject so interesting to the reader or listener. One of his obituarists described how he captured the imagination of a group of sceptical soldiers to whom history was unimportant. It was this skill that made him such a brilliant teacher, and there are many of us who reacquired an appetite for military history through his involvement with the armys Staff College. He had the trick of making that interest and knowledge relevant to todays operational theories. There were 1,300 people at his memorial service; well over a hundred were senior officers who had sat at his feet at some stage or other. He became the professional head of the Territorial Army at a critical moment, and his passionate defence of that organisation which played such a large part in his life marked him out as a fine and selfless leader. The army and the country have much to be grateful to him for.

Richard was at his best on the very ground where a battle was won or lost. He had a good eye for ground and was able to describe in a matter-of-fact way what had occurred at a particular spot. He always related his account to the various hills, valleys, and ridges in front of us, so that you could almost smell and hear the action. His stories of the personalities involved and their unusual habits brought that element of humanity to the story, quite often causing a great deal of mirth. Written notes tended to be just a few headings; it was invariably the way he answered questions that held the crowd.

The soldier, with all his qualities good and bad, was a passion for Richard. He was deeply moved following his two visits to his regiment in Iraq where they had a particularly testing time. Dusty Warriors is his homage to the soldier of today and to the regiment which adopted him a Territorial as their Colonel; he was rightly proud of this unusual accolade. This book shows his devotion to the profession of arms at a very personal level. He much regretted that during his life he had not undergone that test of courage, and Dusty Warriors was, in a strange way, his penance.

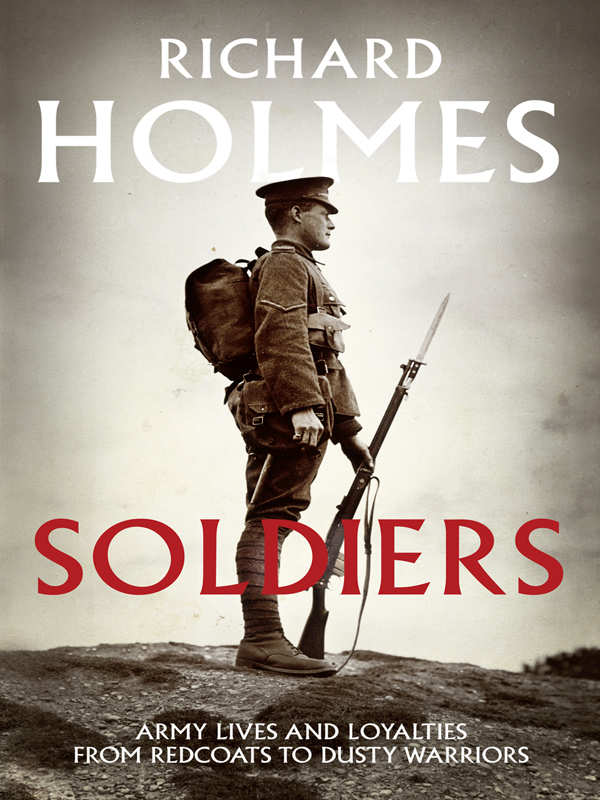

Soldiers is a typical Holmes product, full of detail usefully comparing modern soldiering with the echoes of the past. His technique of bringing perspective to the events of today through the prism of history is always leavened by that inimitable wit for which he was renowned. Having been a private soldier in the yeomanry at an early age he acquired an inner knowledge of how the dynamics of the barrack room worked; this always made him instinctively sympathetic to the plight of the Tom. His trilogy, Redcoat , Sahib , and Tommy are masterpieces of the social history of the British Army but Soldiers adds spice to the mix. Although many will be aware of the lives and loyalties of the British army, few of us are able to describe them in such an amusing and readable way.

As I write this, I am about to embark on another ride in the Borders; we are calling it the Reivers Ride and the choice of country and period were Richards. He was once more to be our companion and resident historian, as we fundraise for his favourite charity ABF, The Soldiers Charity, a charity for which he raised well over a quarter of a million pounds underlining, perhaps, this books theme: that all soldiers deserve our sympathy, praise, and ultimately a hand up. In the weeks before his death, it was this expedition which provided some sort of goal. He will be much in our thoughts as we relive the English victory at Flodden or Cromwells annihilation of the Scots at Dunbar. Jessie and Corinna, his daughters, will be with us for part of the ride, making it all the more poignant. I, for one, will miss those tales perhaps even excerpts from this book which would have been so much better heard than read, but the time lords will have to work their magic before I can enjoy that old familiar voice.

Evelyn Webb-Carter

I T IS USELESS to deny it. I have loved Tommy Atkins, once a widely used term for the common soldier, since I first met him. And love is the right word, for my affection goes beyond all illusions. I know that he is capable of breaking any law imposed by God or man, and whenever I allow myself to feel easy with him, he smacks my comfortable preconceptions hard in the mouth: it is his nature to do so. Antony Beevor, cavalry officer turned best-selling historian, thought that the British soldiers unpredictable alternation between the odd bout of mindless violence when drunk, and spontaneous kindness when sober, is one of his most perplexing traits.1 Another former officer described trying to find some soldiers who were late for duty one Sunday afternoon. He was tipped off that they had been seen entering the house of a local civilian:

The door was answered by a small, rather timid man who invited us in. Were looking for some soldiers, my colleague explained, giving their names. Oh yes, theyre here, the man told us, upstairs, screwing my wife. A few moments later, nine rather shame-faced soldiers appeared with the fattest and ugliest woman I have ever seen. She was quite clearly drunk and farted noisily as she came into the room Later I asked one of the boys what he could conceivably have found attractive in the woman. The more gopping the slag is, Sir, he replied, the better she is at it.2

The same author identified the moment he decided to resign his commission:

At 2 a.m. the Duty Officers phone rang and I lifted it, half asleep, Guardroom Sir, weve got a tech stores man down here he says hes beaten up his wife. I got there in a few minutes to find a very drunk man who had apparently ended an argument with his pregnant wife by kicking her in the stomach. He had got drunk, he told me, because he was fed up with the job and Anyway, that kids not mine. Neither the wife nor unborn child was seriously injured; but that night I decided to leave the Army.3