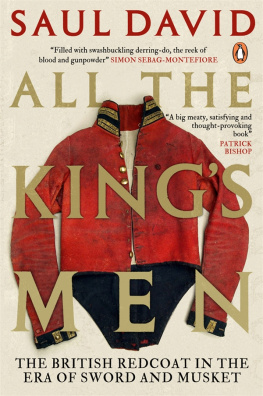

Until yesterday I had not seen any British infantry under arms since the troops from America arrived, and, in the meantime, have constantly seen corps of foreign infantry. These are all uncommonly well dressed in new clothes, smartly made, setting the men off to great advantage add to which the coiffure of high broad-topped shakos, or enormous caps of bearskin. Our infantry indeed, our whole army appeared at the review in the same clothes in which they had marched, slept and fought for months. The colour had faded to a dusky brick-red hue; their coats, originally not very smartly made, had acquired by constant wearing that loose easy set so characteristic of old clothes, comfortable to the wearer, but not calculated to add grace to his appearance. Pour surcroit de laideur, their cap is perhaps the meanest, ugliest thing invented. From all these causes it arose that our infantry appeared to the utmost disadvantage dirty, shabby, mean, and very small. Some such impression was, I fear, made on the Sovereigns, forthey remarked to the Duke what very small men the English were. Ay, replied our noble chief they are small; but your Majesties will find none who fight so well.

Captain Cavali Mercer, Royal Horse Artillery, describing a review of the British army by the Allied sovereigns.

Paris 1815

I HAVE NEVER really got on with Bertolt Brecht, but cannot deny that he had a point in asking, however rhetorically, whether Caesar crossed the Rubicon all by himself. Of course he did not, any more than Cornwall is surrendered at Yorktown on his own, Wellington won Waterloo single-handed, or Cardigan hacked down the Valley of Death at Balaclava with only his bright bay charger Ronald for company. This is not a book about great, or even not-so-great, generals, though both feature in it from time to time. And it is not about battles either, even if we are rarely very far away from them. Instead, its concern is for the raw material of generalship and the pawns of battle, the regimental officers and soldiers (and their wives, sweethearts and followers of a less defined and sometimes rather temporary status) that served in the British army in a century when it painted the world red.

Hollywood is entertainment rather than history, though its tendency to use the past as a vehicle for story telling blurs fact and fiction so that the latter assumes, however unintentionally, the authority of the former. The redcoat has recently featured on the screen in a role depressingly reminiscent of that assigned to the German army after the Second World War. Brutal or lumpish soldiers are led by nincompoops or sadists with the occasional decent fellow who eventually allows a mistaken sense of duty to win the battle with his conscience. Watch Rob Roy, Last of the Mohicans or, most recently, The Patriot, and you will wonder how this army of thugs and incompetents managed to fight its way across four continents and secure the greatest empire the world has ever seen.

That it was an army born of paradox, forged in adversity, often betrayed by the government it obeyed and usually poorly understood by the nation it served, is beyond question. It drank far too much and looted a little too often, and its disciplinary code threw a long and ugly shadow onto the early twentieth century. It sometimes lost battles: we shall see it ground arms in surrender at Saratoga in 1777 and Yorktown in 1781, wilt under Afghan knives on the rocky road from Kabul in 1842, and quail under Russian fire before Sevastopols Great Redan in 1855. Yet it very rarely lost a war. In victory or defeat it had a certain something that flickers out across two centuries like an electric current. Little of that was generated by a military organisation which was a characteristically British mixture of tradition wrapped in compromise, and fuelled by the quest for place, perquisites or status. And, important though high command was, this was an army that fought as hard when mishandled by Beresford at Albuera in 1811 as it did when commanded with genius by Wellington at Salamanca the following year. It drew its enormous tensile strength not simply from the fear of punishment and the lure of reward, though both were important, but from that elusive chemistry that binds men together in the claustrophobic world of barrack-room and half-company, officers and sergeants messes, smoke-wreathed battle line and darkling campsite. If I deplore its many faults, I love it for its sheer, dogged, awkward, bloody-minded endurance, the quality that inspired its exasperated adversary Marshal Soult to complain after Albuera: There is no beating these British soldiers. They were completely beaten and the day was mine, but they did not know it and would not run.

A word about methodology. The architecture of this book is my own, though there is no doubting the fact that I learnt how to ply my ruler and dividers a quarter of a century ago in the Sandhurst drawing office of Messrs Duffy and Keegan. Sir John Fortescues venerable multi-volume History of the British Army (superseded in many areas but still surprisingly useful in others) helped form a solid foundation. For the books framework I am fortunate in being able to rely on scholars who have provided me with the academic equivalent of RSJs, those broad, load-bearing studies, which no professional historian can do much work without. These are works by authors like Alan Guy and John Houlding for the army of the eighteenth century, Michael Glover, Ian Fletcher and Philip Haythornthwaite for Wellingtons army, and Hew Strachan, Edward Spiers and Donald Huffer for the army of the early nineteenth century.

Individual studies provide the equivalent of ducting and plumbing. Brian Robson has made the swords of the period his own, and Howard Blackmore and Christopher Roads have its small arms at their disposal. The Marquess of Anglesey has charted the fortunes of the British cavalry in his multi-volume history. Elizabeth Longfords biography of Wellington remains unsurpassed, though Christopher Hibberts more recent personal history is an easier read. I cannot speak too highly of Mark Adkins study of the Charge of the Light Brigade, and I am grateful that need to amass suitable building materials drew me to Frank McLynns work on crime and punishment in Georgian England, for it was in a part of the yard not often visited by military historians.

Onto this robust structure I have bolted dozens of personal accounts, letting the men who wore the red coat speak for themselves whenever I can. I had encountered some, like John Kincaid and William Grattan, when an undergraduate, and rediscovering them many years on was like meeting a well-preserved old flame in a Kings Parade coffee-shop, and discovering that age has not wearied nor the years condemned. Others were unfamiliar. It is thanks to the Army Records Society that Thomas Browne and John Peebles feature so prominently in these pages, and to Spellmount Publishers that William Tomkinsons Peninsula journal, to name but one of their invaluable books, has escaped from the antiquarian booksellers to which rarity had previously confined it. I have had some pieces of unaccountable good luck: discovering the manuscript Order Book of General Sir William Howe, commander in chief in North America, in the library at the Joint Services Command and Staff College at Watchfield was perhaps the most striking.

So many of the memoirs of the period were written by non-commissioned personnel that I am confident in my denial of the charge that this sort of book is simply epaulette history, giving the officers view. Robert Waterfield, Thomas Morris and John Cooper of the line infantry, Benjamin Harris and Edward Costello of the Rifles, and John Pearman of the light dragoons are amongst those who remind us what it was like to be an atom of an army, as one of their most articulate comrades, Thomas Pococke, actor turned reluctant private soldier of the 71st Regiment, was to put it. And of course there is the incredible John Shipp, twice commissioned from the ranks once for spectacular bravery in the field. I have tried to provide references for all substantive quotations, and list memoirs and collected letters by the name of their writer rather than their editor: the bibliography, really a working list of books actually used, makes this clear.

Next page