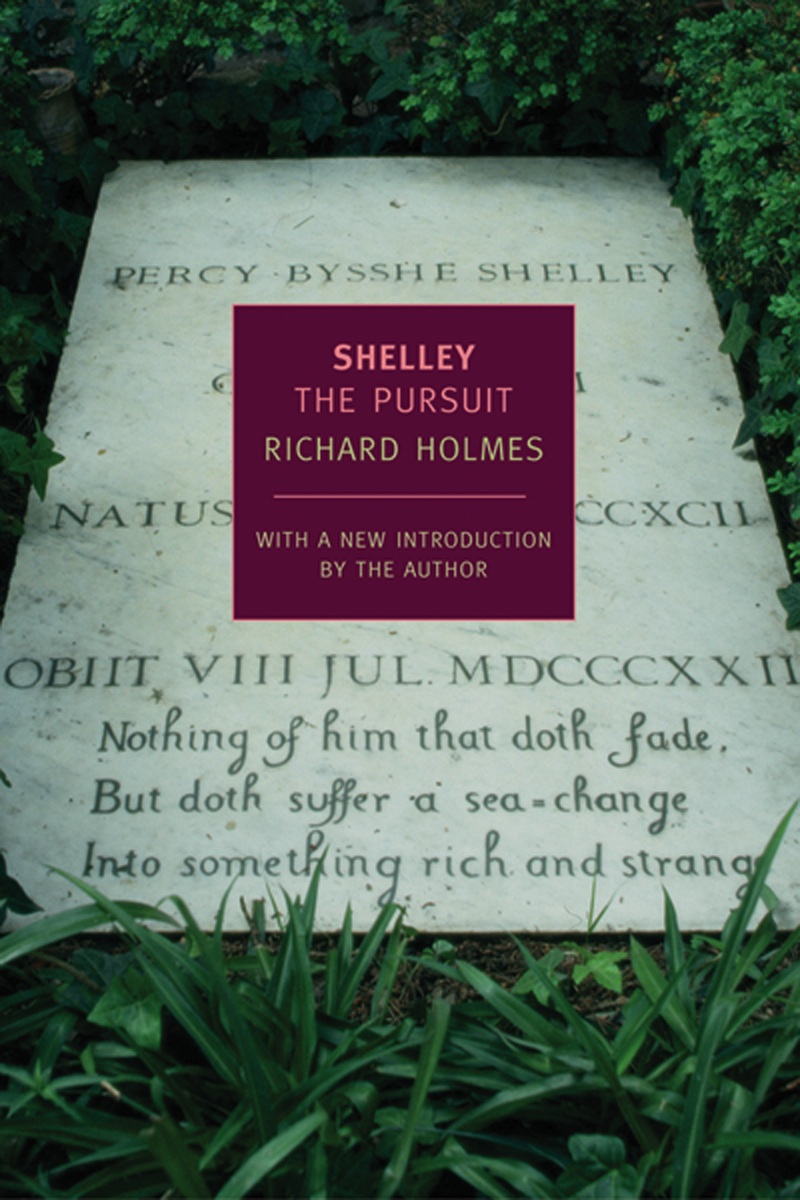

RICHARD HOLMES was born in London in 1945 and educated at Churchill College, Cambridge. Shelley: The Pursuit, his first book, appeared in 1974. It won the Somerset Maugham Award and was described by Stephen Spender as surely the best biography of Shelley ever written... an extraordinary achievement. Among Holmess other works are a two-volume biography of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Coleridge: Early Visions (1989) and Coleridge: Darker Reflections (1998); Dr. Johnson and Mr. Savage (1993); and Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer (1985), which Michael Holroyd has called a modern masterpiece which will be seen as revolutionary a work as Lytton Stracheys Eminent Victorians. Richard Holmes is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and in 1992 was made an officer of the Order of the British Empire. He lives in London and Norwich with the novelist Rose Tremain.

SHELLEY

The Pursuit

RICHARD HOLMES

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

To Helen Rogan and Margaret Amaral

Contents

Illustrations

Section I

Section II

Section III

Photographs not attributed have been taken by the author.

Preface to the New Edition

This is a young mans book. I completed it at the age of 29, the same age at which Shelley drowned in the Gulf of Spezia. It shares something of the recklessness of its subject, the pursuer and the pursued. I think it should remain like that. It is an attempt to write literary biography as a form of modern epic, in which speed of action, colour and movement, travel and the sense of poetic adventure, predominate over everything else. I always go on until I am stopped, said Shelley, and I never am stopped. I still think this is the essential truth about his remarkable life, which continues so vividly into the present day, a restless and demanding presence for each younger generation to encounter.

Looking back after twenty years, I see more clearly the partialities and enthusiasms in what I researched and wrote, angrily rejecting much of the critical tradition, returning to original sources, and following Shelley everywhere over his own ground through England, Ireland, France and Italy. I have described the intense, dreamlike obsession of this work a process of trial and error and self-education in my later book, Footsteps. I have made some corrections and reparations (especially to Mary Shelley) there. But I believe the political and philosophical focus of the biography, the sense of Shelleys energy and intellectual power, his impetuous physical impact on all those around him, still holds good. So I am content, on reflection, to let the book stand as a true history of my time in Shelleys company. Others wiser and more scholarly than myself will continue to correct it, and to that end I have included a New Select Bibliography of more recent studies, many critical of aspects of my own work, which I urge the reader to consult. But above all I urge the re-reading of Shelleys poetry and essays, especially after 1816: no other Romantic writer learned, and changed, and developed his art so swiftly.

The open-ended nature of biography is one of its mysterious attractions. No Life is ever definitive: it draws or rejects from past work, it reflects often unconsciously the concerns and questions of its own age, and it passes on something hidden to the future. Every serious attempt at an historic portrait of the dead will subtly absorb the milieu and temperament of its living author, however objective he or she sets out to be. This is precisely the strength, rather than the weakness, of its subjectivity. It is the vital element that Hippolyte Taine, the first great European theorist of biography, curiously overlooked in his efforts to define a scientific genre of Life Studies, as a sort of human botany. Biography is only scientific in the sense that it is experimental: it tests one version of the facts. But all good biography must do more, must risk more, if it is to live for any time in the imagination. It must finally transcend facts and documentation, and risk an artistic style and form appropriate to its age.

It is now evident to me that this biography, as I put it in Footsteps, was written by a child of the English 1960s. Nevertheless that happened to be a particularly fruitful moment to rediscover Shelleys story, with its special explosive mixture of fantasy, poetry and radical ideas, so close to the passionate hopes and aspirations of that time. If the present age of the fin-de-sicle is a darker and less certain one, Shelleys peculiar energy and idealism may stand out even more forcefully, a sharp flame against the shadows. What makes him cruel, and even absurd, may also gather a particular and poignant resonance. He, in the end, was a child of the European Enlightenment, and believed that the world could be revolutionized by language, and that fire was the element of imagination.

Much has changed in Shelley studies since I wrote. The Victorian penumbra has dissolved, the shade of Dr Leavis has retreated, and Shelley is again popular with students, though his extra-curricular attractions remain thankfully high. A brilliant effort of textual refinement and republication has continued in America, under the scholarly leadership of Donald H. Reiman with the resources of the Carl H. Pforzheimer Library in New York and the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Following K. N. Camerons pioneering work, much has been clarified in Shelleys socio-political background. A new generation of literary critics has championed Shelleys intellectual gifts, his sceptical idealism, and the glimmering metaphorical subtleties of his poetic language. Both deconstructionist and feminist critics have been drawn to his work, with often dazzling results. A notable, and properly maverick, group of British writers and scholars including William St Clair, Paul Foot, Howard Brenton, Claire Tomalin, Angela Leighton, Timothy Webb and P. M. Dawson have explored much that is new and controversial. There have been Shelley novels, Shelley plays, and Shelley films. A valuable scholarly survey and listing of much of this work is available in The New Shelley: Later Twentieth Century Views, edited by G. Kim Blank (St Martins Press, New York, 1991); and I have included a careful choice from, the whole field in my New Select Bibliography.

Some things do not change. Andr Mauroiss charming Shelley Romance, famously entitled Ariel (the first Penguin biography of 1925), was dashingly re-issued for Shelleys bicentenary. It was a book that I mockingly referred to in my original Introduction, as the cause of much mischief in Shelleys after-life. I found myself in the ironic position of being asked to write a brief panegyric for the back-cover of the new edition (Pimlico, 1991). My feelings about Ariel had not changed, but I had come to respect Maurois as an embattled pioneer of French biography, especially in his Lives of Victor Hugo (1954), The Three Dumas (1957), and above all Balzac (1965), which have still not received proper recognition in French criticism. Disguised in the hectic persona of a blurb-writer, I therefore tried to fit Mauroiss early and influential experiment with the romanced form into the larger development of Shelleys twentieth-century biography. I reprint here what I finally wrote after much misgiving for it bears on the whole complicated question of how biographies grow out of date, and yet may still retain a significant literary presence.