This book is dedicated to my parents Wolfgang and Joan van Emden

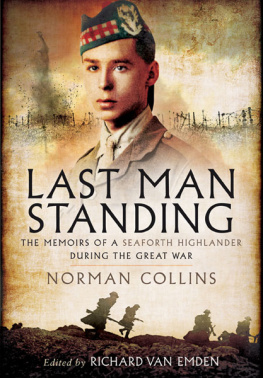

Other books by the author:

Tickled to Death to Go

The Memoirs of a Cavalryman in the First World War

Veterans

The Last Survivors of the Great War

Prisoners of the Kaiser

The Last POWs of the Great War

The Trench

First published in Great Britain in 2002 by Leo Cooper

Reprinted in 2012 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Richard van Emden 2002, 2012

ISBN 978 1 84884 865 8

EPUB ISBN: 9781781597750

The right of Richard van Emden to be identified as Author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

By CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

My especial thanks must go, first and foremost, to Normans son, Ian Collins, whose patience, encouragement and kindness have been unfailing. I am very grateful to Ian for entrusting to me all of Normans possessions from his service in the Great War, including all his notebooks and photographs.

I should also like to thank the staff of the Department of Documents in the Reading Room of the Imperial War Museum. As keepers of Normans letters and postcards - sent during his service at home and at the front - they have all been extremely helpful during my frequent visits to the archive.

Many thanks must go to Roni Wilkinson at Pen and Sword Books who, as usual, has put up with the shenanigans of Richard van Whatsit, as I have always affectionately been known to him. Roni has produced a book that Norman would have been proud of, as I am. I must also thank both Charles Hewitt and Brigadier Henry Wilson at Pen and Sword Books for their continued faith in me.

A very big extra thank you must go to my parents, Joan and Wolfgang van Emden. My books are invariably dumped on them at short notice as deadlines draw near, yet they never fail to cast their eyes over a text where, inevitably, there are important corrections to be made. Their efficient editing of this book has been invaluable, as has my fathers translation of a letter written in German and found by Norman in 1917, (see page 151)

I would also like to thank Anna, my partner, whose encouragement and cups of coffee have been unending, despite her own high-pressure job.

Finally, there are many others whom I would like to thank for various and disparate reasons, including Steve Humphries, Peter Barton, Dave Bilton, Steve Grogan and Vic and Diane Piuk.

PICTURE CREDITS

Norman Collins private collection, taken 1917-1918 David Bilton

The Imperial War Museum

The Taylor Library

The Tank Museum, Bovington

Queens Own Highlanders Museum, Fort George

Introduction

It has been commonly said that the average life expectancy at the front of a Second Lieutenant in World War One was approximately six weeks before he was either killed or wounded. In this respect, and in this one respect only, my friend Norman Collins was no better than average. He arrived on the Somme in late October 1916 and was wounded in early December six weeks. In late April 1917 he returned to France and was slightly wounded in late May five weeks; then he was wounded for the third and final time in the second week of July six weeks. His 17 weeks at the front were to put him in hospital for a total of 14 months and give him a lifetime of pain that no disability pension could ever compensate for.

I knew Norman for only three years but in that limited time I found him in every other way exceptional. I met him through my work in television, when a colleague happened to mention that Norman had contacted the company in response to an appeal for veterans of the First World War. Norman, as I was to find out, had already been seen on television, in BBC2s Nineties series; he had also appeared in a couple of Imperial War Museum books.

We quickly found that Norman was one of those rare veterans who had an almost photographic recall of his war service and it was decided that we should film him straight away. In the end, we recorded his memories for at least three different programmes, such was his clarity of mind and eloquence of speech.

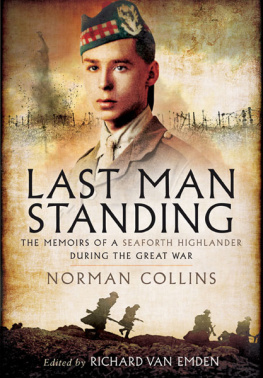

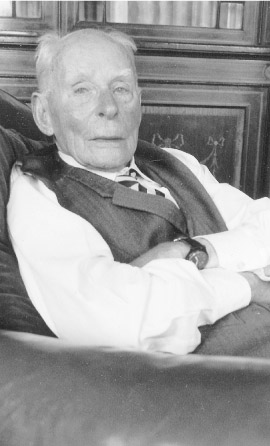

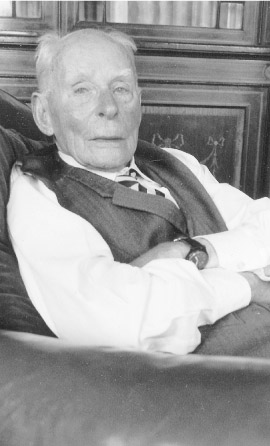

Norman Collins aged one hundred.

With most interviewees, contact is sadly fleeting and usually finishes after the broadcast of the programme, but I found Norman so fascinating that I returned to see him, and a friendship developed. In time, I was very proud to be invited to his 100th birthday in 1997, and very sad, yet honoured, to attend his funeral in February 1998. Even now, it doesnt seem possible that Norman has been dead for over four years. He was one of those people who will always stay alive to those who met him and therefore will never quite seem gone. This book is, I hope, a fitting tribute to him.

When I met Norman, he had recently moved to a village close to Peterborough, a town which had been his home for many years, and where he lived in what was reputedly the towns oldest house. As Normans eyesight had deteriorated, he had moved in with his son, Ian, cementing yet further a very close relationship between the two. Even though Ians work frequently took him overseas, they spoke daily on the phone. As Norman became less mobile and his war injuries caused him considerable pain, he took to tape recording a daily diary of the events around him as well as his own recollections of his long life. Invariably his war memories came to the fore and tapes sometimes labelled just Random Recollections often held invaluable details from his war story. These tapes could have become the basis of a biography and indeed, during one of my visits, Norman mentioned that he was looking for someone to write his story. Although inwardly enthusiastic to volunteer, I felt unable to offer through pressure of work. Nevertheless, I had a recurrent and niggling feeling that I was passing up a wonderful opportunity. From that moment onwards, I felt certain that I would return to Normans story.

Norman (top)

Next page