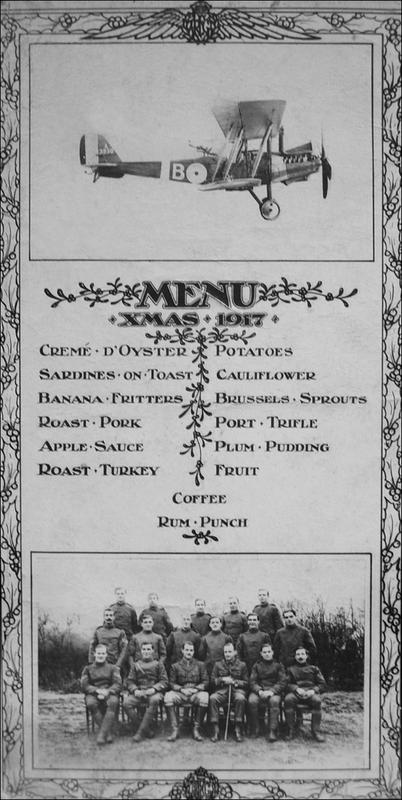

This is the menu for the officers mess, No. 9 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, Christmas 1917. The biplane is a Royal Aircraft Factory RE8, known as the Harry Tate. Note the upward-firing exhaust pipe just in front of the pilot. What exactly Crem dOyster was has puzzled French scholars for almost a century.

I n contrast to the treats lined up for those lucky officers of No. 9 (pictured opposite), it looked like being a turkey-free Christmas dinner in the officers mess, No. 266 Squadron, until Second Lieutenant Bigglesworth remembered flying over a flock of turkeys somewhere behind enemy lines. He thought hed go and liberate one.

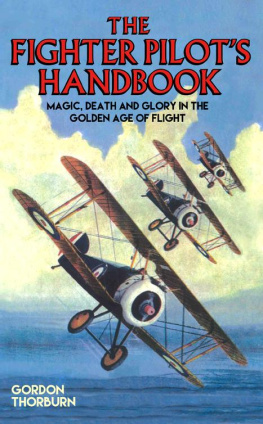

He landed his Sopwith Camel in a field by the farm. After several alarums, during the description of which we learn that our intrepid hero weighed ten stone, which makes him smaller than we imagined, he took off, struggling in the tiny cockpit to contain the violent protests of a very large turkey, all alive-o, and pursued by small-arms fire from German soldiers.

Soon in unseen pursuit was an Albatros fighter (aka Haifisch, shark), probably a D Mark 5, called the V-strutter for its wing-strut arrangement, possibly one of the new Mark 5As, or possibly even an old Mark 3 (also a V-strutter). The turkey by now had got itself wedged between pilot and seat-back, in which unfortunate position it absorbed a few bullets from the specially lightened LMG08/15 version of the Spandau 7.9mm machine gun that would otherwise have killed Biggles. Assessing the situation in an instant, Biggles stowed the dead and therefore manageable turkey on the cockpit floor and turned his undivided attention to his attacker.

Biggles spun the Camel round in its own length and shot up in a climbing turn that brought him behind the straight-winged machine. That the pilot had completely lost him he saw at a glance, for he raised his head from his sights, and was looking up and down, as if bewildered by the

Camels miraculous disappearance. Confidently, Biggles roared down to point-blank range. The German looked round over his shoulder at the same moment, but he was too late, for Biggles hand had already closed over his gun-lever.

He fired only a short burst, but it was enough. The Albatros reared up on its tail, fell off on to a wing, and then spun earthwards, its engine roaring in full throttle. [Biggles of 266, by Captain W E Johns, originally published in The Modern Boy in December 1934.]

By Christmas 1917 the Albatros D3, previously the best fighter at the Front, had lost its primacy, outperformed by the Sopwith Camel, the Royal Aircraft Factory SE5A and other Entente machines; and the Albatros D5 was not a great enough improvement. By the time new types came in, it was too late for the German air force.

By Christmas 1917, the Albatros D3 (pictured) was obsolete, outperformed by the Camel, the SE5A and other Entente machines, and the Albatros D5 was not a great deal better. By the time new types came in, it was too late for the German air force.

The Camel was so manoeuvrable it could be unstable in the wrong hands and quite a few learner pilots were killed in this aircraft. It could turn remarkably quickly to the right, helped by engine torque, but tended to go nose down, which Biggles obviously knew how to overcome.

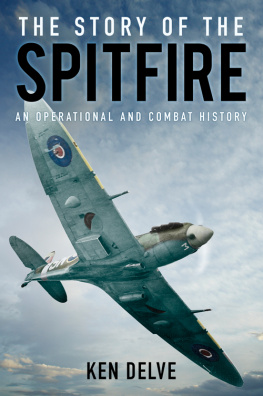

The real 266 Squadron, formed at the end of the Great War, was disbanded a year later like so many and re-formed in December 1939 to fly Spitfires in the Battle of Britain. The squadron was disbanded for good in 1964.

William Earl Johns flew in the First World War but not in Sopwith Camels. Called up in 1914 as a Norfolk reserve soldier, he was with the Yeomanry at Gallipoli and the Machine Gun Corps at Salonika. In 1917 he received his commission as second lieutenant and his transfer to the Royal Flying Corps as trainee pilot.

The new Royal Air Force, established 1 April 1918, had Johns as a flying instructor but he was just in time to see some action when posted to 55 Squadron in August 1918, flying DH4 bombers into Germany.

The squadron raided Mannheim on 16 September. After taking damage from anti-aircraft fire, Johns was set upon by Fokker D7 fighters, said to be of Jasta 4, the unit of Ernst Udet (q.v.) and shot down, although not by Udet himself, who was on sixty victories at the time.

Johns, wounded, survived the crash but his observer did not, so the pilot stood alone in the dock at Strasbourg to be found guilty of indiscriminate bombing of civilian targets, a crime that carried the death penalty. Why the sentence was not carried out is uncertain; Johns was in a POW camp when the war ended.

He stayed in the RAF until 1927 with one promotion, from pilot officer to flying officer, the equivalent of army lieutenant, and began writing over a hundred Biggles stories in 1932 but he never was a captain.

The real story that brought Biggles to life was as remarkable as any of his adventures. Imagine a fellow inventing the musket and showing it to His Lordship. I say, says the impressed noble. Jolly useful, what? Could knock down no end of pheasants with that.

Yes, my lord, says the inventor. But I have a cunning plan. What about using it in battle?

In battle? Good heavens, no. By the time youve reloaded, youll have been run through. No, no. Swords and horses, thats what we want in battle. Swords and horses.

It wasnt quite as one-eyed as that with aeroplanes; but it wasnt far off.

The Sopwith Camel was so manoeuvrable it could be unstable in the wrong hands. Note the dihedral angle (the upward angle from horizontal) of the lower wings, unlike the straight-winged machine Albatros, which had no dihedral. This helped stability about the roll axis, or in the spiral mode; but it is unlikely the full aeronautical significance of the dihedral effect was understood by the Camels designers.

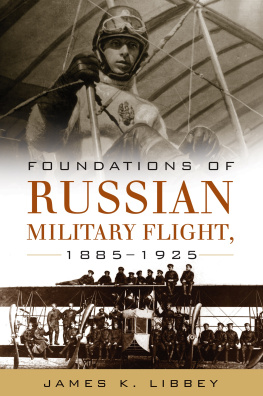

THOMAS MOY AND HIS AERIAL STEAMER

Towards conquering gravity by machine rather than gas bag, most of the practical work was done between 1891 and 1905. Before that, there were always people wanting to imitate birds, flapping wings in an effort to fly, and as long ago as 1799 came the first theoretical description of the kind of machine people would need, if they were ever to be able to fly usefully.

Sir George Cayley, 17731857, Yorkshire baronet, lord of the manor of Brompton-by-Sawdon in the North Riding near Scarborough, set out the basic principles at that time and in a more detailed paper published in 1809. He understood that we should have to replace flapping wings with fixed ones, and that flying surfaces would need to be curved to produce sufficient lift to overcome the drag, that is, the combined weight of the flying machine, plus its burden of aeronauts, plus its motive force, an engine. Steam engines, he said, would never do, but some new sort of engine would be required, so that forward motion could generate the aforementioned lift and the craft could journey purposefully from A to B.