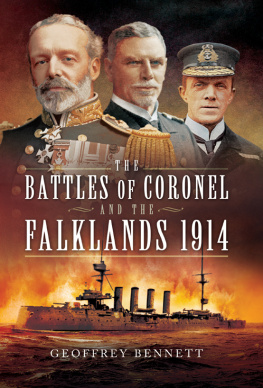

Pen &Sword

MILITARY

This edition published in 2014 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

The right of Geoffrey Bennett to be identified as author of this work

was asserted for him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act 1988.

First published in 1962 by B. T. Batsford Ltd

and re-printed by Birlinn Limited in 2000

Copyright Geoffrey Bennett 1962

Preface and Addendum Rodney M Bennett 2000, 2013

ISBN: 978-1-78346-279-7

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon,

CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen

& Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History,

Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CONTENTS

Within three months of the outbreak of the First World War the incomparable reputation which the Royal Navy had earned in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries suffered a blow that was the more bitter because it was wholly unexpected; one of Britains cruiser squadrons was decisively defeated by a superior force from the new-born German Navy. The scene of the action was off the coast of Chile, half the world away from Plymouth, Portsmouth and the Nore, but the Admiralty reacted with such vigour that within six weeks the disaster was avenged; reinforcements sailed from Scapa Flow to the Falkland Islands, nearly 10,000 miles, and sent the victorious German force to the bottom of the South Atlantic. This dramatic reversal of the fortunes of war explains why more books, many with the interest inherent in participants accounts, have been published about the Battles of Coronel and Falklands than about any other naval action, those between major fleets excepted.

In this new account, however, I have attempted the first comprehensive study to be written since the British and German official histories were compiled nearly forty years ago by authors who could not tap all the sources now open to the historian. In the words of Gilbert White: These observations are, I trust, true on the whole, though I do not pretend to show that they are perfectly void of mistake, or that a more nice observer might not make many additions since subjects of this kind are inexhaustible. Nor can I pretend that these observations are wholly objective; that is more than can be expected of a writer who belongs to one of the participating nations; inevitably I have been conditioned by the British viewpoint; moreover I have been able to consult a larger number of British sources. Nonetheless, I have done my best to fulfil the historians duty of being fair to both sides, withholding from neither such admiration and criticism as each seems to warrant. For history cannot be written without criticism, any more than an omelette can be made without breaking eggs. But this is no excuse for the denigration of British and German leaders of the First World War which is now the fashion; they had their merits or they would not have attained high rank. Nothing extenuate, nor set down aught in malice: I have highlighted achievements as well as pointed mistakes; remembering, for example, that, whilst Churchills denial of responsibility for the British defeat at Coronel was unjust to Cradock, he also displayed the qualities of genius which were to earn for him a unique place in history 30 years later; that, despite Fishers shabby treatment of Sturdee after his victory at the Falklands, he did more than any other man to prepare the Royal Navy for the First World War; and that, though von Spees dilatory progress after Coronel and his decision to attack the Falklands combined to bring about the destruction of the German East Asiatic Squadron, its voyage across the Pacific which culminated in Cradocks defeat is as much to the German admirals credit as the gallant way he fought and died.

| London, 1962 | GEOFFREY BENNETT |

The Great War, the First World War, the War to End Wars, those horrendous four years have a number of names, so the centenary of its outbreak brings with it the inevitable look backwards. It is then appropriate for further issue of what I believe was my late fathers definitive account of the two naval actions, disaster then triumph, which opened that conflict at sea. When he wrote, about half a century ago now, the Falkland Islands were a little known or thought-about far-away and insignificant British outpost. That it has figured significantly since should not lead to any confusion; these events have no connection with any attempt to capture those islands.

I have given this edition an Addendum with additional material mostly based on his papers now held by the Caird Library in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. These include the usual correspondence from readers which follow any such publication as well as comments from reviewers. In this reproduction of the original it has not been possible to include these directly in the text.

It should not be forgotten that these events took place after more than a century during which the Royal Navy had had no significant engagements not since Trafalgar. In that period the warship had morphed from wind-driven sailing galleys armed with short-range muzzle loading cannons to steam-powered steel-hulled leviathans with massive breech-loading armament reaching beyond the horizon. Yet much of this technology was in its infancy; my father explains the limitations of radio communication in his Appendix. The regular need to re-coal was a particularly strong restraint on even the most determined commander.

A word about my father (19081983). He was a rare naval historian who had actually commanded a warship at sea. Born into naval family he entered Dartmouth as a cadet at fourteen where he first developed his strong interest in naval history. He made the usual career path, qualifying as a Signals specialist which meant he held several Flag-Lieutenants post to various Admirals in the 1930s. His war years started with a short visit to Norway and a substantial period as Signals Officer in West Africa at Freetown, a base for many of the vital Atlantic convoys. After a spell teaching at H.M.S. Mercury, the Signals School, back home he became Signals Officer in the Mediterranean under the formidable Admiral Sir Charles Willis who recommended him for a DSC; the citation reads: ...for leadership and skill while serving as signals officer on the Staff of Flag Officer Force H since April 1943 in operations which finally lead to the surrender of the Italian Fleet. I had the privilege of seeing him receive this at Buckingham Palace from King Gorge VI.

His post-war career included a spell in command of