First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

Pen & Sword Maritime

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Bryan Perrett 2012

9781783033904

The right of Bryan Perrett to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11.5pt Bembo by Mac Style, Beverley, East Yorkshire Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

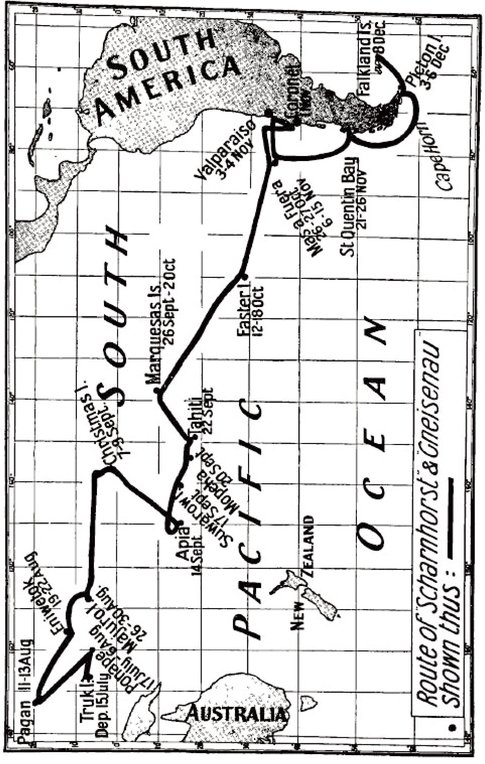

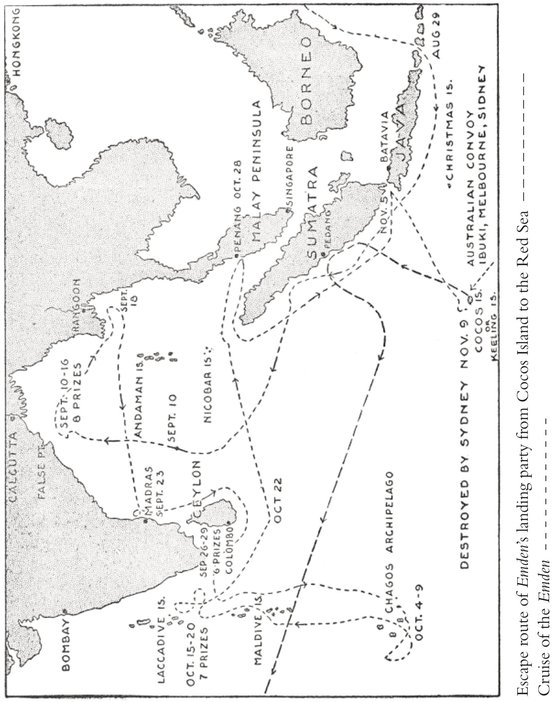

The movements of the German East Asia Squadron, 15 July to 8 December 1914.

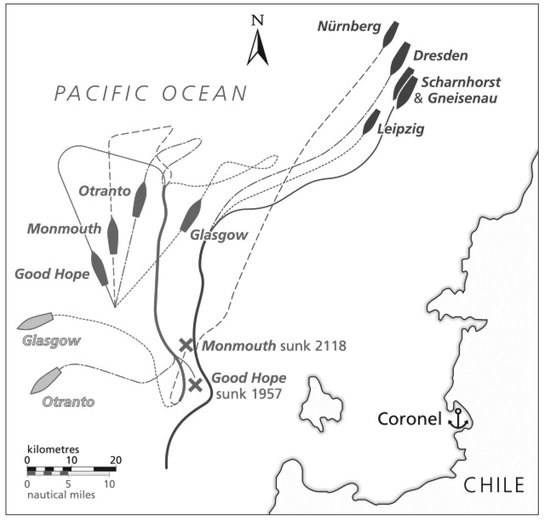

The Battle of Coronel, 1 November 1914.

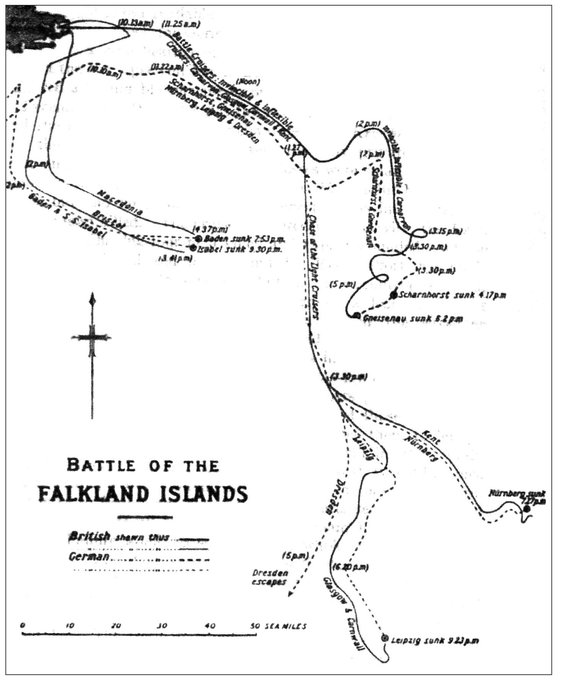

The Battle of the Falkland Islands.

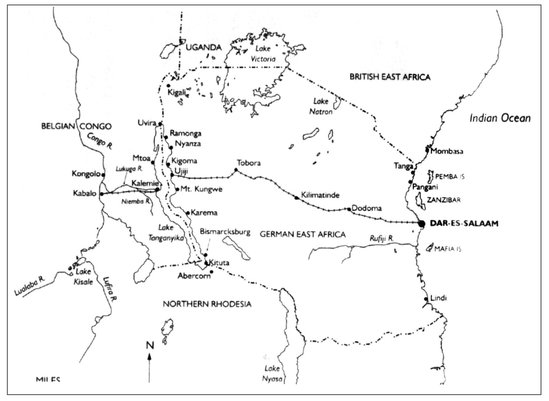

German East Africa and Lake Tanganyika.

Introduction

T his is a story of ships and men, of battles fought a hundred years ago on the major oceans of the world, battles largely forgotten or unheard of that formed part of a war between empires vanished long since. When war between Great Britain and Imperial Germany began to seem inevitable the German Admiralty gave considerable thought as to how best British mercantile traffic could be damaged. The High Seas Fleet, built at enormous cost, was in any event designed purely for operations in the North Sea and the Baltic and quite unsuited to the guerre de course. The U boat arm was in its infancy and the number of boats at its disposal was initially small. Again, its activities rarely extended beyond the North Sea, the English Channel, the Western Approaches to the United Kingdom and the Mediterranean Sea. On the other hand, Germany possessed colonies dotted around the world and these provided bases for surface warships. These consisted mainly of cruisers, but there were also a number of gunboats that would provide the armament for passenger liners that were earmarked for service with the Imperial Navy. The major problem involved was to keep regular and auxiliary warships supplied with coal. Colliers were chartered and supplies purchased close to where they would be needed. Inevitably, the German raiders would be operating in a climate of secrecy and an ingenious system was devised in which warships would replenish their fuel in coded grid-squares in remote ocean areas. In this way they were able to remain at sea for long periods, supplementing these supplies with more fuel and provisions taken from their victims.

Naturally, this course of action was predicted and allowed for by the British Admiralty in its dispositions. The Royal Navy of 1914 was the largest and most powerful in the world, yet its opponents enjoyed a number of advantages. Most of the Royal Navy, including its largest and most modern warships, was concentrated in the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow in anticipation of a major clash in the North Sea with the German High Seas Fleet. That meant that despite its numerous bases in British colonies and dominions around the world the Royal Navy was required to police the worlds oceans with comparatively few ships in relation to the vast areas involved. This not only required widespread dispersion, but also prolonged employment for its older ships, some of which were on the verge of retirement. It therefore did not follow that in any engagement between British and German cruisers the former would always enjoy numerical and qualitative advantages. It also meant that the Germans enjoyed the benefit of surprise and were able to strike at targets of their choice without warning. At the outbreak of war, for example, most people would have regarded the idea of a German cruiser bombarding Madras on the coast of India as being absurd. Thus, when it actually happened, the shock involved was the greater. Another factor which worked to Germanys advantage was that, with the exception of troop convoys, the Admiralty refused to introduce a system of escorted ocean convoys until May 1917. Until then, merchantmen made individual sailings, just as they had in peacetime, and were easy prey for the raiders. The provision of a single gun on the poop deck as defensive armament did little to deter the raiders with their multiple armament, although some British masters chose to make a fight of it, with inevitable results, although in one such engagement the raider was so battered that she came close to joining her victim on the bottom.

This, however, was a war in which those who hunted merchantmen were themselves being hunted by Allied warships. By the middle of 1915 all of Germanys pre-war cruisers that had been stationed abroad had been sunk or neutralised. They had, however, given a good account of themselves, sinking three British cruisers, one Russian cruiser and a French destroyer, as well as an impressive tonnage of merchant ships and their cargoes. Their loss was, of course, regretted in Germany, where it was decided that their work would be continued by commerce raiders. These were usually converted merchantmen armed with concealed guns and they possessed the ability to disguise their appearance with dummy funnels, upperworks, masts and foreign identities. Some produced good results but others achieved little. Again, they were too few in number and too widely scattered across huge expanses of ocean to have had a decisive influence.

It might be remembered that the introduction to one of the filmed versions of Anthony Hopes novel The Prisoner of Zenda informed audiences that the story was set in a time when politics had not outgrown the waltz and history still wore a rose. Of course such an era never existed although the concept was pleasant enough. Nevertheless, unlike some aspects of the maritime war, this particular area of operations was conducted in a notably chivalrous spirit and in accordance with the life-saving traditions of the sea. Killing could not be avoided altogether, but it was never wanton. Unless sea conditions and the tactical situation prevented it, the crews and passengers of sunken ships were accommodated and received decent if confined treatment until their numbers grew to the extent that raider captains had to send them into a neutral port aboard one of his captures.