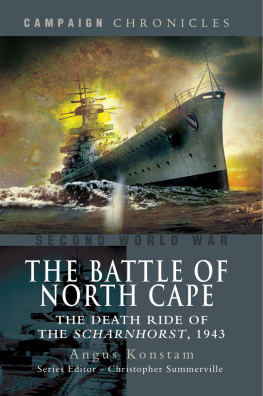

DEATH OF THE SCHARNHORST

John Winton

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1: HITLER AND HIS ADMIRALS

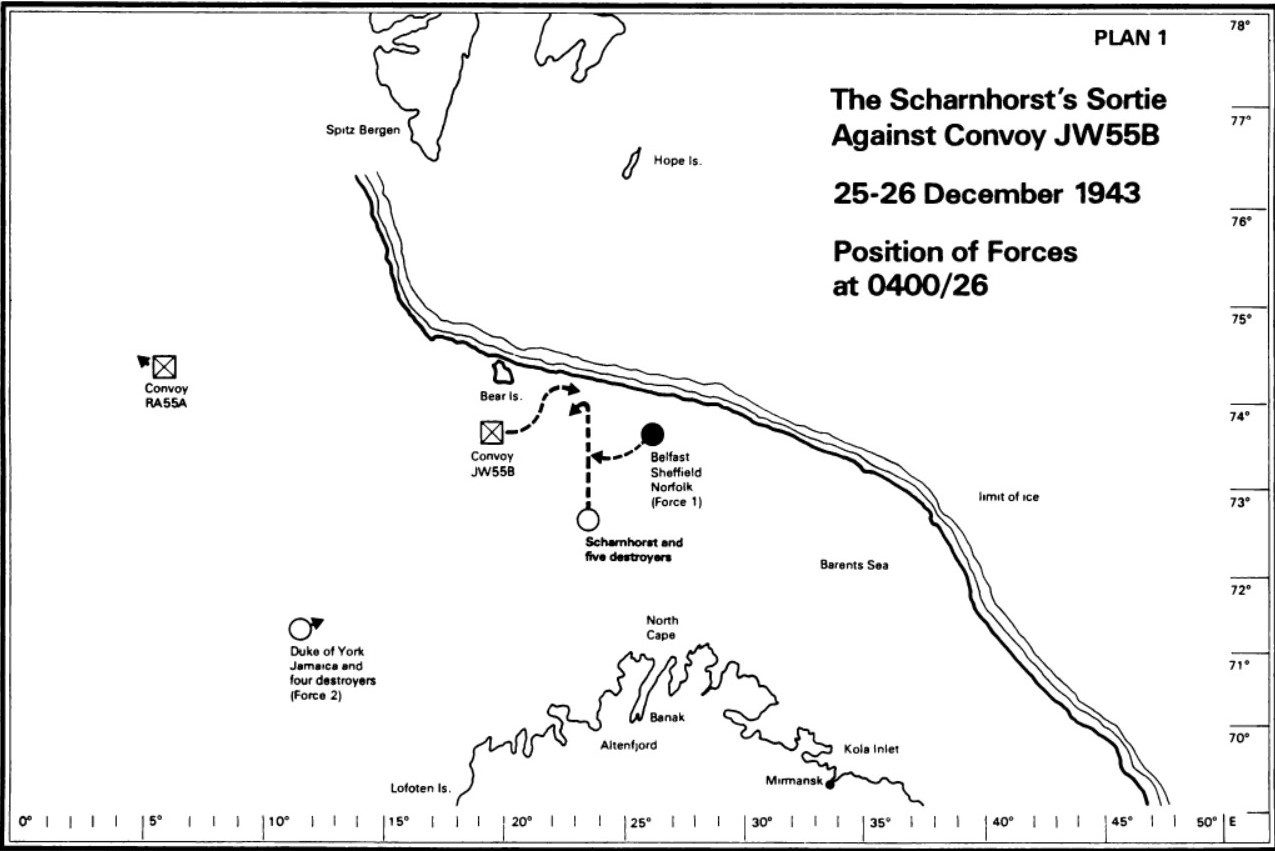

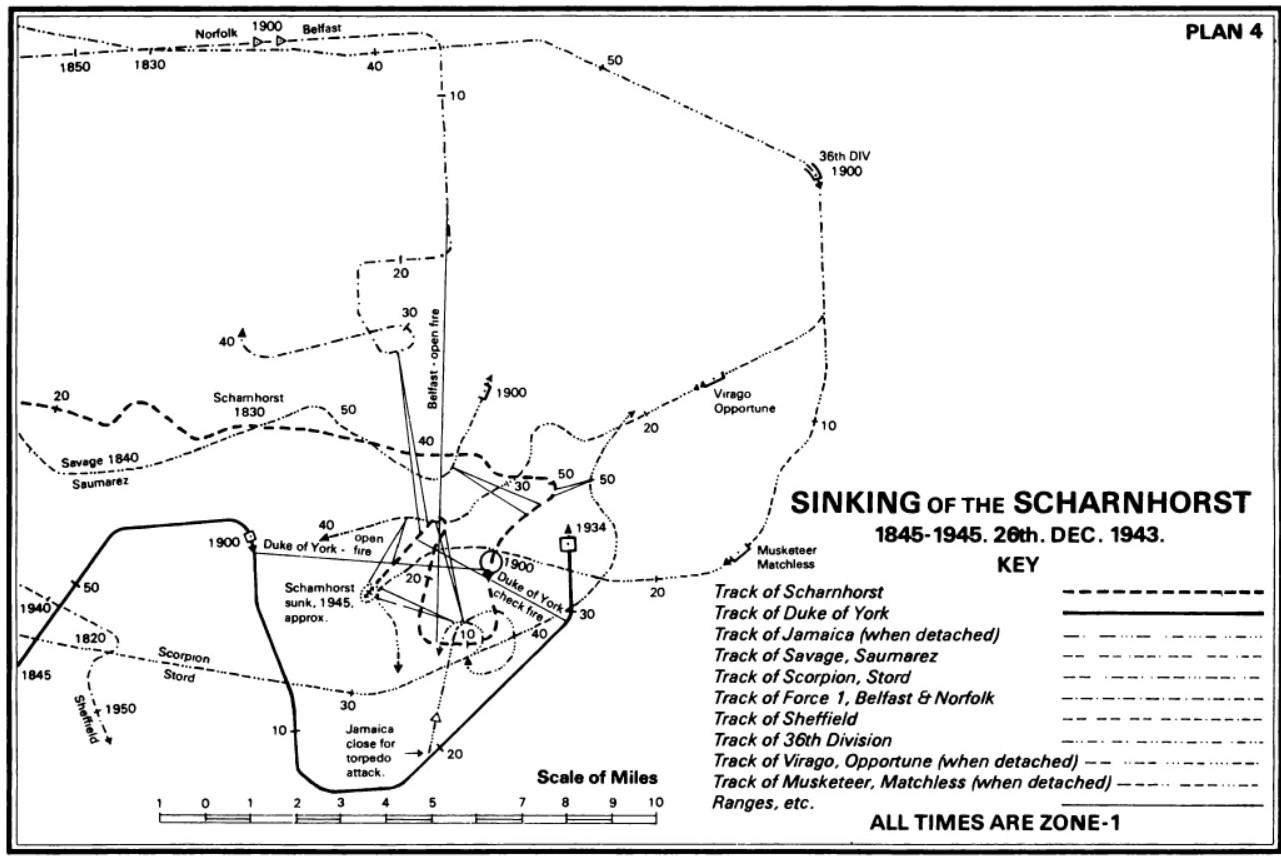

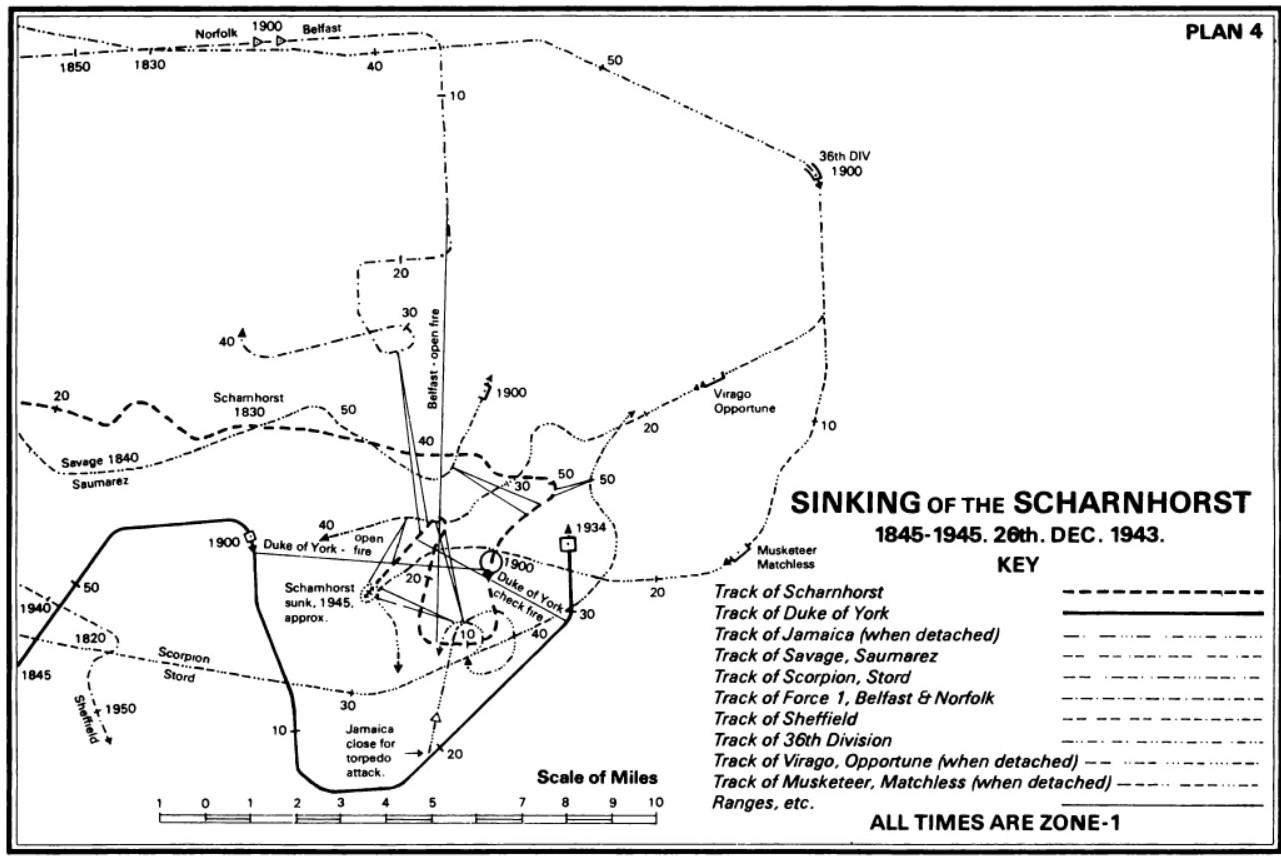

EVERY time we hit her, it was just like stoking up a huge fire, with flames and sparks flying up the chimney. Every time a salvo landed, there was this great gust of flame roaring up into the air, just as though we were prodding a huge fire with a poker. Tremendous, unforgettable sight. So said Lieut. Vernon Merry RNVR, the admirals flag lieutenant, watching from the flag bridge of the battleship Duke of York , off the North Cape of Norway, late in the evening of 26th December 1943. It had been a long day, which was just reaching its climax, when ships of the Home Fleet, led by their Commander-in-Chief Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, had sighted, chased, and trapped and were now finally about to sink the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst .

It was a curiously old-fashioned naval engagement, like a head-to-head combat between maritime dinosaurs, a slogging match between two giant capital ships, in which aircraft played no part. It was also a classical demonstration of two widely different national views of sea power.

Adolf Hitler, a land animal and a very successful one, had only a limited grasp of naval affairs. He always wanted his Navy to triumph in battle, but not to suffer any losses. He took each success as a personal compliment, each loss as a private affront. It is significant that both Bismarck and Scharnhorst , in their last hours, transmitted personal signals to the Fuhrer; His Majesty King George VI, though himself a naval officer, would doubtless have been flattered but still extremely surprised to have received similar signals from one of His Majestys Ships in action.

Hitlers contradictory philosophy of sea power naturally affected his commanders. Constantly being urged onwards to victory for Fuhrer and Fatherland, whilst at the same time being strictly cautioned against taking any risks with their ships, Hitlers admirals seemed easily depressed. For them the line between glory and gloom was very thin, and one unlucky torpedo hit, as with Bismarck , or one crushing salvo, as with Scharnhorst , was quite enough to breach it.

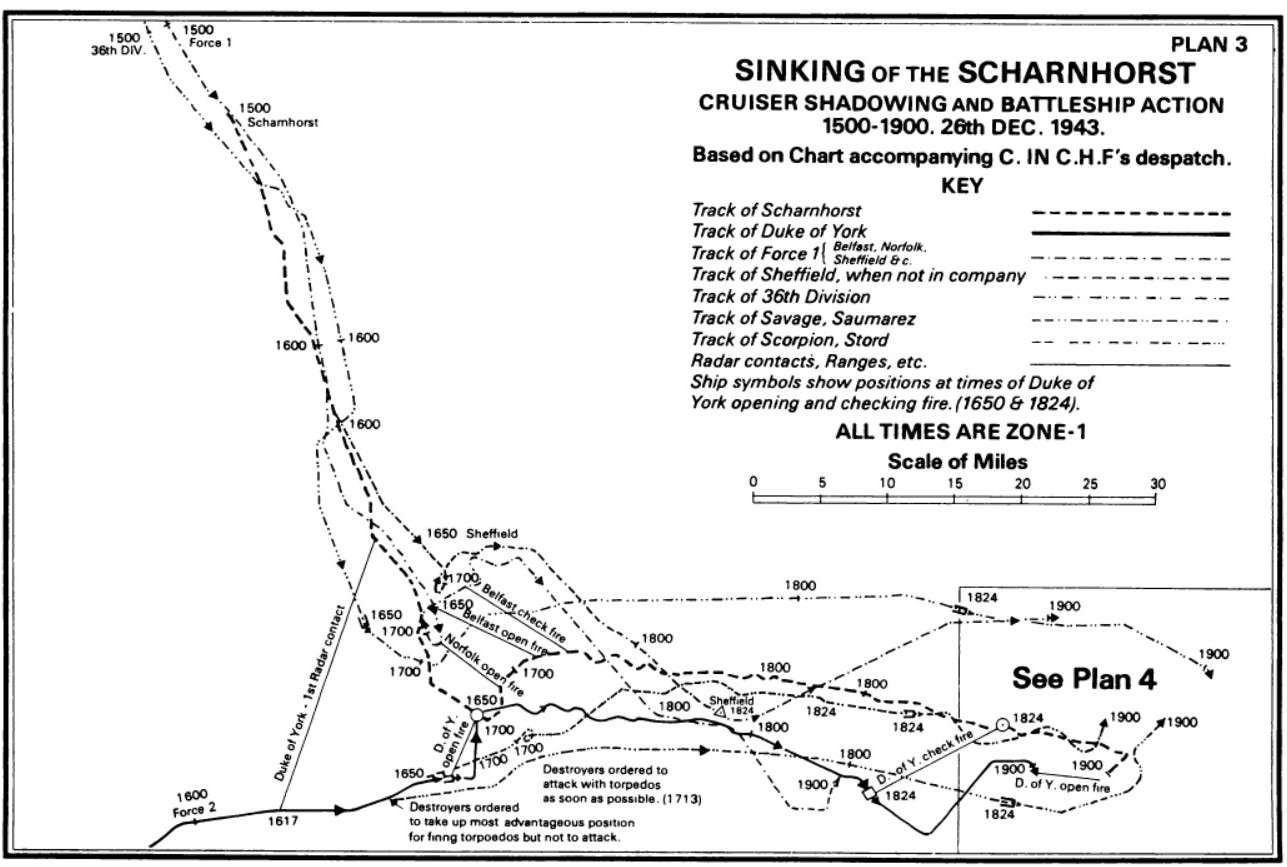

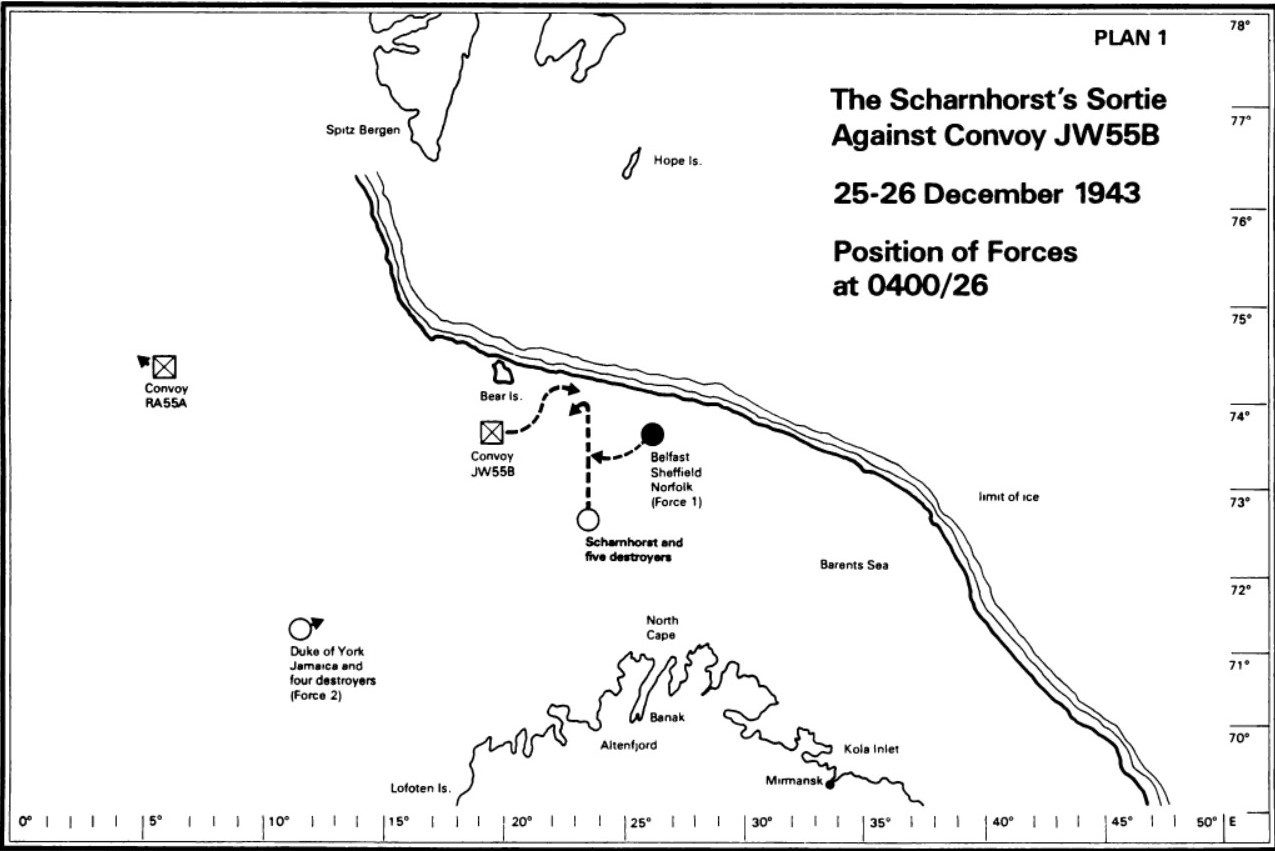

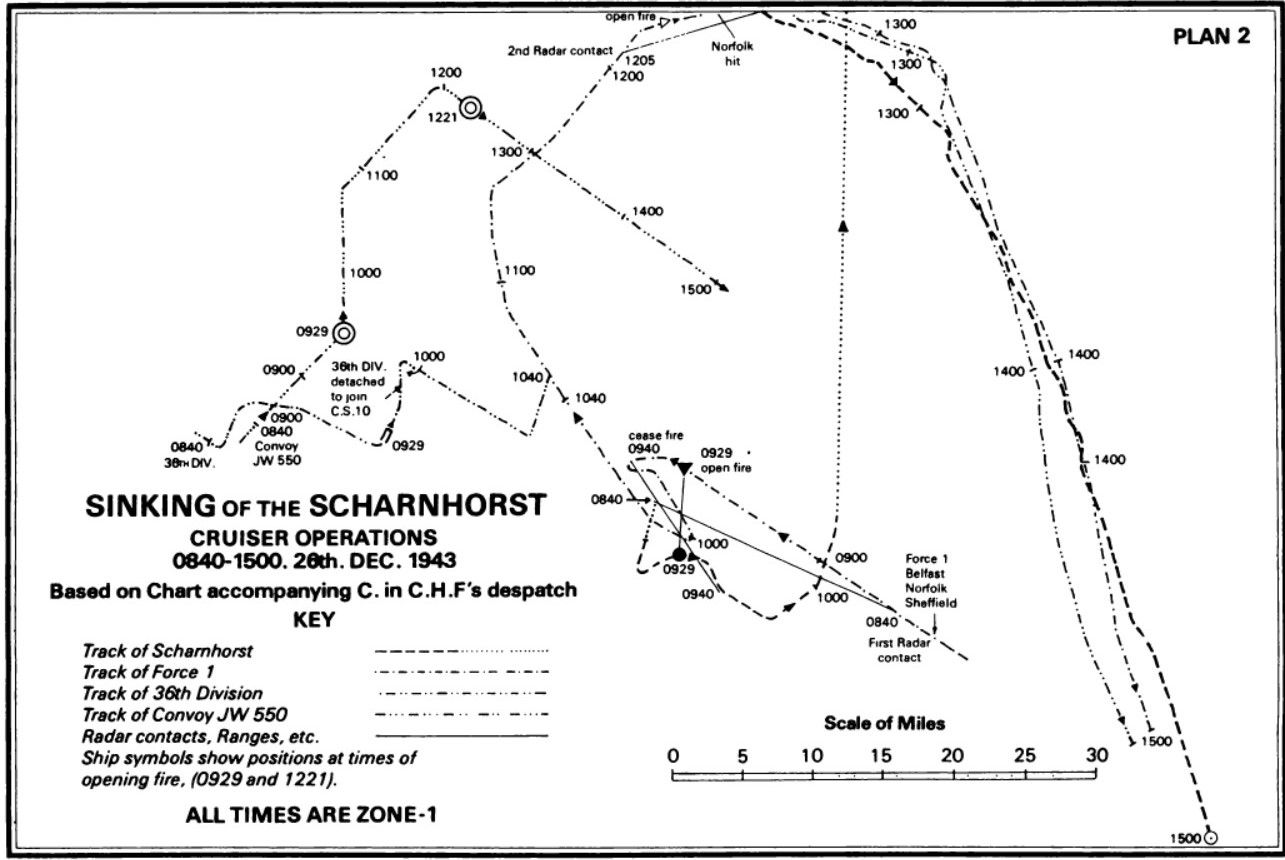

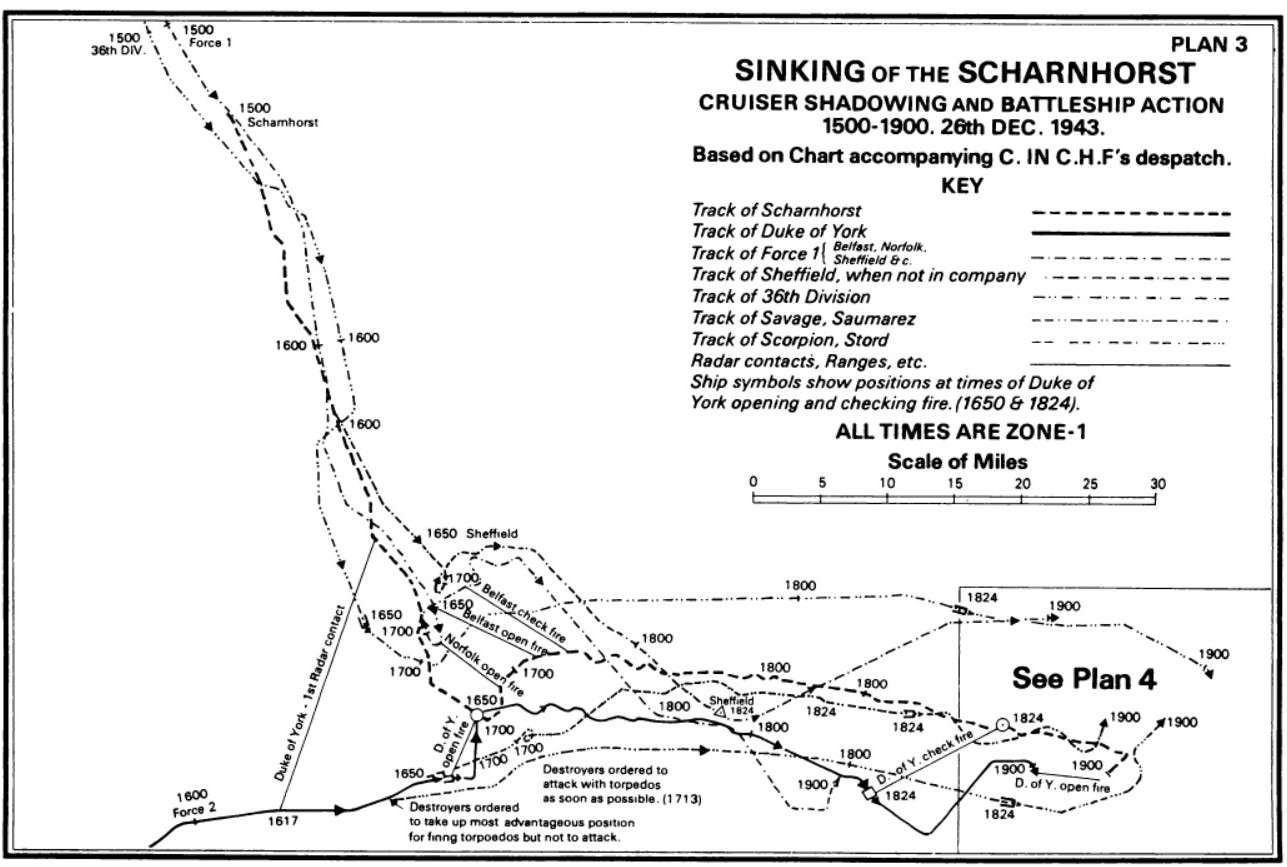

In Scharnhorst s last action, the German ships put to sea with a very sound strategic purpose, but they were feebly directed and ineptly handled. The German commander, Rear Admiral Erich Bey, took his ships out knowing very well what he was supposed to do, but evidently with little idea of how to do it. He had more than one chance to accomplish his purpose. While trying to find his target he was counter-attacked by smaller but determined opponents and allowed himself to be driven off. Finally, in trying to evade, he chose the very course which was sure to take him almost directly into the arms of his most powerful adversary of whose approach he had been quite unaware.

The Royal Navy, on the other hand, has always known that the price of Admiralty is very high indeed, in blood and treasure. But one setback does not lose a war. In Bruce Fraser the Home Fleet had a commander, on the day, at the top of his considerable form. He had always known who his opponent would be, sooner or later, and he had had ample time to think over what he was going to do and how he should do it. When the chance came, Fraser handled his forces with a sure touch. He knew when to break radio silence with advantage. He was well served by an able cruiser admiral in Robert Burnett, by the bravery of his destroyer captains, by professional and technical excellence in his ships and by a good personal staff, by ample and timely intelligence, and, finally, by the heavy guns of his flagship Duke of York . Frasers reward was a model action, in which a fast and formidable enemy, actually better suited to the weather conditions that day than any other warship present, was methodically hunted down and brutally dispatched.

Scharnhorst and her sister-ship Gneisenau Salmon and Gluckstein as they were sometimes popularly called were two of the most famous ships of the Second World War, on either side. They were built after the lifting of the limitations imposed on the German Navy by the Treaty of Versailles, and were originally intended for a war in which France was envisaged as Germanys only opponent; these two ships were designed to intercept and destroy the convoys bringing troop reinforcements back to France from West Africa.

Scharnhorst was laid down at the Marinewerft, Wilhelmshaven, on 16th May 1935, launched on 3rd October 1936, and commissioned, under her first commanding officer, Kapitan zur See Otto Ciliax, on 7th January 1939. She displaced 38,900 tons full load, of which some 12,500 tons was Krupp armour, in places nearly 14 inches thick. She had nine 28 cm. (10.92 inch) guns in three dual turrets, twelve 15 cm. (5.85 inch) guns, fourteen 10.5 cm. (4.095 inch) guns, and numerous 37 mm. and 20 mm. anti-aircraft guns, with six 53.3 cm. (20.8 inch) torpedo tubes in two triple mountings. She carried four aircraft. Her three shafts gave her a top speed of 32 knots and she had an operational range of some 10,000 miles at 17 knots. She was 770.5 feet long, 98.4 feet in the beam and drew nearly thirty feet at full draught. The Germans called her a battleship, the Allies termed her a battle-cruiser; with her bows fully lengthened and flared, she was one of the most beautiful naval ships ever built.

Scharnhorst and her partner in crime as the British public thought of Gneisenau were both in the headlines from the earliest days of the war. On their first war cruiser in November 1939, it was Scharnhorst who sank the hopelessly outmatched armed merchant cruiser Rawalpindi , on the Northern Patrol, south of Iceland; this was an episode which Scharnhorst s crew, who had already begun to think of themselves as an elite, did not consider as redounding to their credit. One of Scharnhorst s survivors said it left an unpleasant taste in my mouth.

In April, off Norway, they were both in action again, against the battlecruiser Renown and later, in June, they sank the aircraft carrier Glorious and both her two escorting destroyers Ardent and Acasta . In January 1941, their teamwork reached its peak when they sailed on an extended raid on commerce. By the time they returned in March, two months later, they had brilliantly carried out their main purpose as raiders, having sunk or captured 22 ships, of 115,622 tons, and totally disrupted Allied convoy schedules for some time and over a very wide area. They had also tempered valour with discretion, having adroitly withdrawn on three occasions when they sighted an opposing capital ship with a convoy.

But this cruise was the summit of their achievements. At Brest, where they reached harbour on 23rd March 1941, both ships were subjected to harassing air attacks. In February 1942, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau , with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen , who had joined them after her own cruise with Bismarck , with an escort of destroyers, made their celebrated Channel Dash and returned home to Germany in a boldly conceived and skilfully executed operation which greatly alarmed the people of Great Britain that enemy heavy ships could pass so close to their coastline. Certainly the German squadron had wiped the Allies eyes in passing through the Dover Straits almost unscathed, but the ships were far less dangerous to the Atlantic convoys in Germany than they had been at Brest.

Next page