Published in Great Britain and

the United States of America in 2018 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

Introduction and chapter introductory texts by Chris McNab

Casemate Publishers 2018

Hardback Edition: | ISBN 978-1-61200-657-4 |

Digital Edition: | ISBN 978-1-61200-658-1 |

Kindle Edition: | ISBN 978-1-61200-658-1 |

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

The information and advice contained in the documents in this book is solely for historical interest and does not constitute advice. The publisher accepts no liability for the consequences of following any of the advice in this book.

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Fax (01865) 794449

Email:

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casematepublishers.com

Cover design by Katie Gabriel Allen

INTRODUCTION

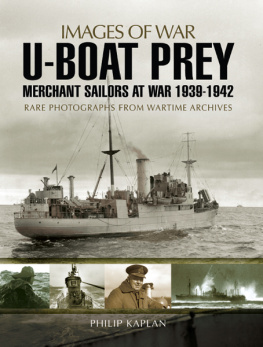

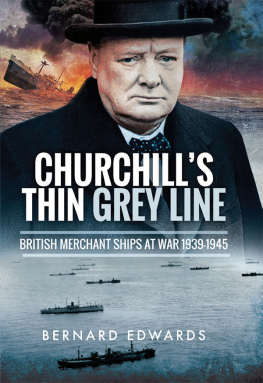

O n 12 September 1939, scarcely a week after the German invasion of Poland and the onset of hostilities between Germany and Britain, the British king, George VI, issued a message via the nations newspapers. It addressed a very specific group of people, who although they did not serve in the armed forces were nonetheless utterly central to the survival of the United Kingdom in the expanding conflict:

In these anxious days I would like to express to all Officers and Men and in The British Merchant Navy and The British Fishing Fleets my confidence in their unfailing determination to play their vital part in defence. To each one I would say: Yours is a task no less essential to my peoples experience than that allotted to the Navy, Army and Air Force. Upon you the Nation depends for much of its foodstuffs and raw materials and for the transport of its troops overseas. You have a long and glorious history, and I am proud to bear the title Master of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets. I know that you will carry out your duties with resolution and with fortitude, and that high chivalrous traditions of your calling are safe in your hands. God keep you and prosper you in your great task.

George VI knew, and was doubtless reminded by his government advisors, that to a large degree the future victory or defeat of Britain lay in the hands on its non-combatant merchant fleet. As an island nation, Britain was disproportionately reliant upon maritime imports. All of its oil, now vital for keeping the wheels of war industry running, was shipped in from abroad, as was 54 per cent of its iron ore, 93 per cent of its lead and 95 per cent of its zinc. On the domestic side, some 70 per cent of food was imported, including 91 per cent of the countrys butter, 70 per cent of its cereals and fats, 50 per cent of its meat and 80 per cent of its fruits. It was apparent to all, especially in light of the punishing experience of the U-boat campaign during the previous world war, that the greatest threat to Britains sustained resistance to Nazi Germany was the severing of its Merchant Navy lifelines.

Eclectic Service

The Merchant Navy, as it was known by the onset of World War II, should not be regarded as a holistic entity, like the Royal Navy. In reality, the term was essentially a convenient conceptual label, bestowed by King George V following World War I, for what was actually a swarming mass of independent and physically diverse commercial shipping. Under the title Merchant Navy, therefore, fell a typology of vessels in which the only unifying factor appeared to be that they all floated on water. They included (based on the 1940 publication His Majestys Merchant Navy ): ocean-going liners, intermediate liners, cargo liners, refrigerated ships, fruit ships, cargo ships (themselves of numerous types), colliers, tankers, whale-oil ships, cross-channel packets, continental and Thames excursion steamers, paddle steamers, timber carriers, coastal ships, short sea traders, cable ships, tugs, ferries, harbor craft, canal craft, ore carriers, river boats, cruising ships, hospital ships, troopships and fishing vessels. The men and, more rarely, women who served aboard these vessels were as contrasting as the ships themselves, ranging from university-educated officers to ships boys from rough parts of industrial Britain. In November 1939, the writer Montague Smith described the archetypical British merchant sailor in the Daily Mail : He is usually dressed rather like a tramp. His sweater is worn, his trousers frayed, while what was once a cap is perched askew on his tanned face. He wears no gold braid or gold buttons: neither does he jump to the salute briskly. Nobody goes out of his way to call him a hero, or pin medals on his breast. Nohe is just a seaman of the British Merchant Service. Yet he serves in our Front Line today.

Despite its often ragged appearance, the Merchant Navy carried with it international prestige. It was the worlds largest merchant marine. In 1938 it had more than 192,000 personnel, including 50,700 Chinese and Indian sailors. Yet if Britain was to sustain the war effort, many more sailors and more boats would be required. Finding the right levels of manpower was at first problematic, because merchant sailors were, to all intents and purposes, casual, non-military labour. At the outbreak of war, the sailors were given the option of switching to less hazardous land-based careers, or joining the armed forces, but those who decided to stay in the service still labored from contract to contract, unpaid when work dried up.

Desperate Times

This situation produced some evident absurdities. For example, if a sailors ship was attacked and sunk, the moment the ship slipped under the waves the sailor (if he survived) was no longer paid. Such commercial heartlessness was given real substance by the terrible losses already being suffered by the Merchant Navy at the hands of German aircraft, mines and, above all, U-boats. The first ship sunk by the Germans was the transatlantic passenger liner Athenia , destroyed on 3 September 1939 by U-30 370km (229 miles) north-west of the northern tip of Ireland. But by the end of that month, another 51 vessels had been destroyed, and by the end of the year, a total of 165 ships had been downed.

Far worse was to come the following year. The German conquest of Western Europe meant that Frances Atlantic ports fell under Kriegsmarine control. U-boats could now sail easily and directly into the British Atlantic sea lanes. Further campaigns were launched in the Mediterranean, although the U-boat threat there was limited by the narrow and British-controlled entrance to the Mediterranean at the Straits of Gibraltar. (This didnt stop the Merchant Navy in the Mediterranean being harried by German and Italian maritime aircraft and surface vessels.) Both the increasing numbers of U-boats and the improving German Wolf Pack tactics inflicted hideous losses on the ships and sailors 1,059 vessels in 1940 rising to 1,299 in 1941.