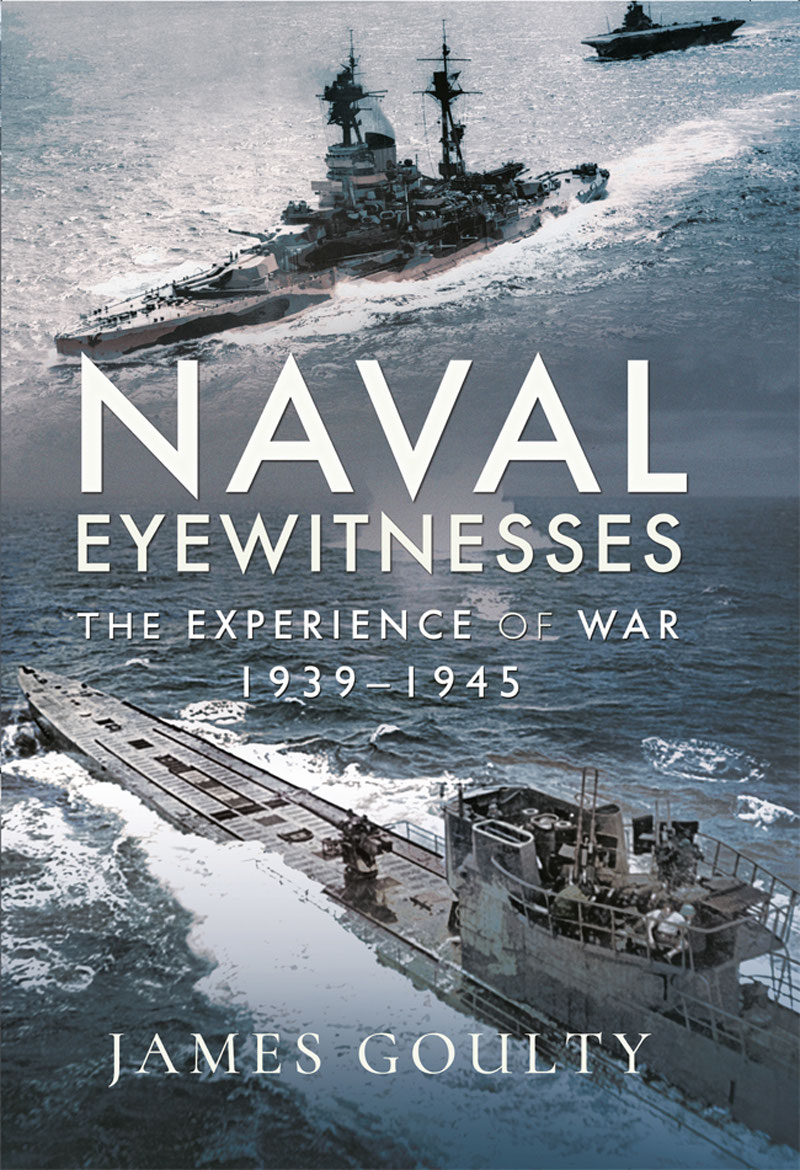

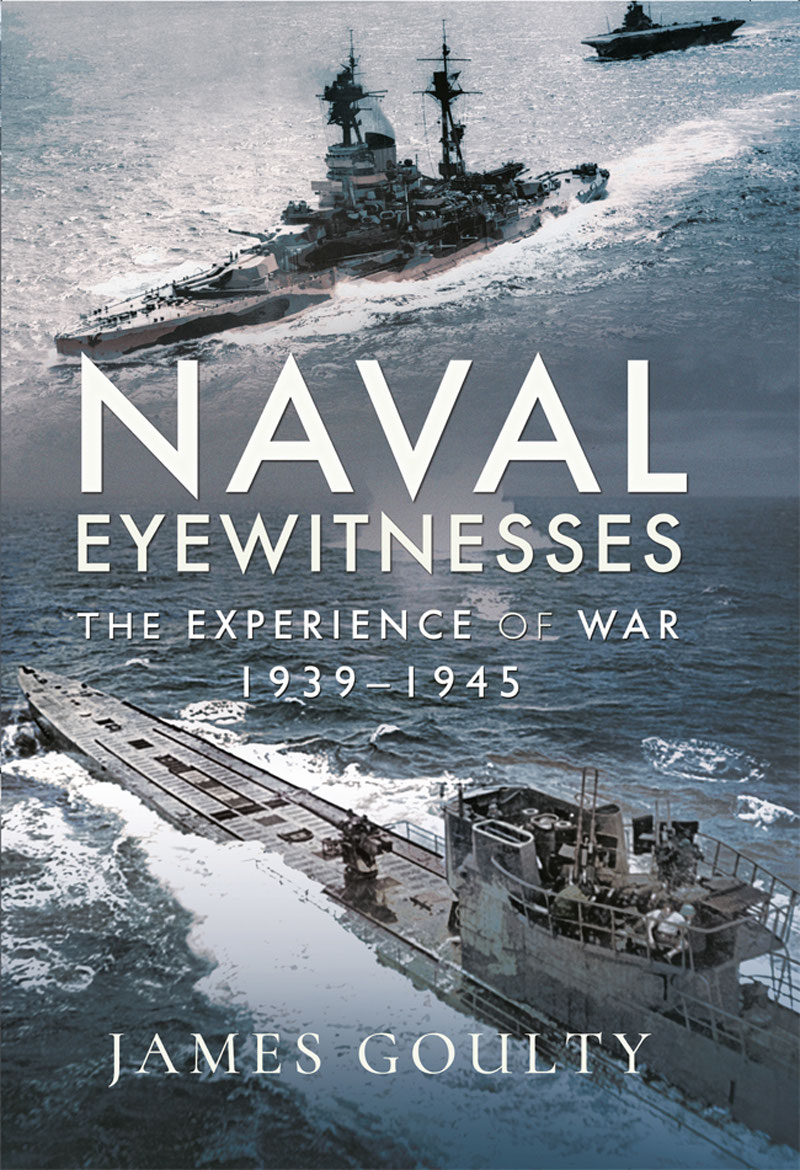

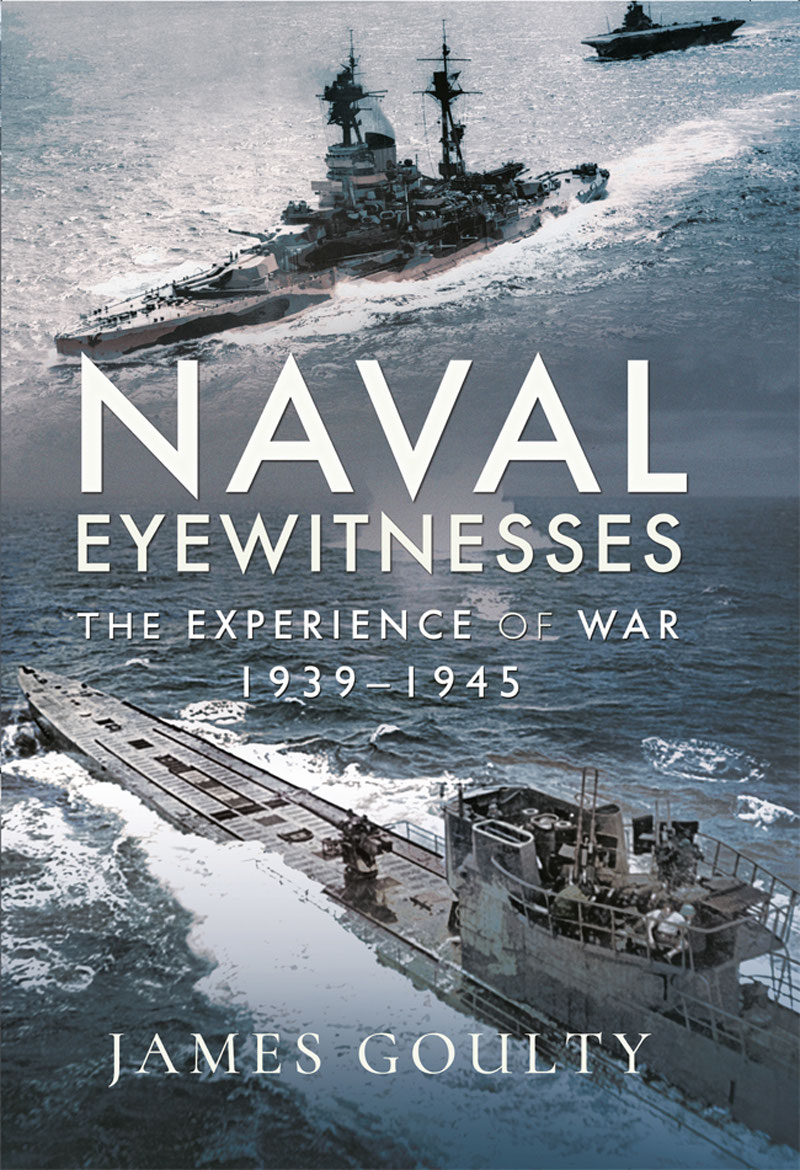

Naval Eyewitnesses

The Experience of War at Sea 19391945

James Goulty

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by

PEN & SWORD MARITIME

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright James Goulty, 2022

ISBN 978-1-39900-071-0

ePUB ISBN 978-1-39900-072-7

MOBI ISBN 978-1-39900-072-7

The right of James Goulty to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Aviation, Atlas, Family History, Fiction, Maritime, Military, Discovery, Politics, History, Archaeology, Select, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Military Classics, Wharncliffe Transport, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, White Owl, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Books.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN & SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail: uspen-and-sword@casematepublishers.com

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Contents

1.Big Ships and Smaller Vessels

2.Naval Aviation and Aircraft Carriers

3.Underwater Warfare and Anti-Submarine Warfare

4.The Experience of Convoy Work

5.Amphibious Warfare

6.Discipline and Morale

7.Demobilisation and Reflections

Preface

In 1939 the Royal Navy was one of the instruments that helped bind the British Empire together. It ensured that the then large British merchant fleet could freely manoeuvre across the worlds oceans without interference, and protected the country. Those joining the Royal Navy were frequently made aware that they were effectively inheriting this proud tradition, so that any actions on their part that marred this image would not be tolerated. Consequently, as an institution the Navy was inherently conservative, but this sense of tradition tended to appeal to recruits, even in wartime, when the service was compelled to absorb large numbers of reservists and Hostilities Only (HO) personnel. Total strength was over 863,000 by mid-1944, including 72,000 members of the Womens Royal Naval Service (WRNS). Certainly many of the men and women whose personal testimonies are drawn upon in this volume appear to have developed a deep attachment to the Senior Service, and to have been immensely proud of their war service. Similarly, the reader will find plenty of instances where officers and ratings enjoyed aspects of their service, despite the privations of wartime.

However, it is important to remember that the war at sea was just as brutal and stressful for its participants as the war on land or in the air. British naval casualties for the entire war were 1,525 ships of all types lost, equating to over 2 million tons of shipping, and over 50,000 personnel killed, many of them from the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR). An example of the cruel nature of naval warfare was the loss of SS Aguila in August 1941. A small, slow-moving transport ship, she was sailing to Gibraltar when her convoy was assaulted by a number of U-boats, one of which torpedoed her. According to her skipper, who survived, it was like potting a sitting bird. Twelve Wren cypher officers, ten Chief Wren special operators and a naval nursing sister were killed instantaneously. This led Vera Laughton Mathews (Director WRNS, 19391946) to describe the sinking as: One of the worst blows our Service suffered.

Likewise, 28,000 seafarers aboard British merchant ships were killed during the war, and thousands more died from wounds suffered during their service or in collisions and coastal shipwrecks resulting from the conditions of war. Equally significant was the loss of 4,800 merchant ships, equating to 21.2 million tons. Had the supply of food, raw materials and armaments from overseas been wholly severed, then it is unlikely that Britain would have been able to continue the war. Merchantmen were equally important during the amphibious operations embarked upon by the Allies, as the war gradually shifted towards the offensive. During Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943, for example, around 500,000 tons of shipping was assembled. This included fourteen British hospital ships and five hospital carriers, plus merchantmen operating as troopships and those bringing in supplies and equipment and evacuating POWs. Merchant shipping also had an important role in the build-up of Allied forces in Britain as a precursor to the opening of the Second Front in June 1944.

A number of sources have been consulted for this volume, notably naval histories, reference books, personal memoirs and the oral testimony of veterans. Full details of these can be found in the accompanying bibliography and chapter notes. Readers might similarly appreciate the sequence of events in the Timeline, which provides additional background for the personal experiences narrated in the text. As many wartime recruits discovered, the Navy was a distinctive organisation with its own language or slang, plus it was as prone to employing acronyms as did the army and the RAF, all of which contributed towards its corporate identity. Accordingly, the accompanying Glossary might also help readers.

Personal experiences clearly varied depending in which branch of the Navy an individual served. Chapter 1 deals with life aboard capital ships, such as battleships, and contrasts this with service aboard smaller vessels, including destroyers and minesweepers. As one of the veterans who joined before the war testified, there was a distinct difference between big ship men and little ship men, and this carried over into the war. Naval aviation and aircraft carriers form the subject of the second chapter. The Fleet Air Arm had its own strong identity, making it almost a navy within a navy. As the chapter explains, it was deeply unfortunate that tensions between the Royal Navy and the RAF over the development and control of naval aviation blighted the inter-war period, and was only being resolved on the eve of war. For the crews of aircraft carriers their experience was also a special one, with intense comradeship. Another strand of the chapter considers the various types of small carriers, including escort carriers and MAC ships, whose contribution has perhaps been overshadowed in the public consciousness by that of the larger carriers, such as the famous HMS Ark Royal.

Aspects of underwater warfare, notably submariners, and the experiences of Charioteers (human torpedoes) are highlighted in Chapter 3. To complement this, attention is also given to anti-submarine warfare (ASW), and its essential role in winning the Battle of the Atlantic. Similarly, Chapter 4 discusses convoy work, with reference to both naval experiences and those of merchant seamen. Convoys were one means of countering the U-boat threat in the Atlantic, and required a high degree of skill and seamanship, both from the escorts and the merchantmen constantly trying to maintain station. Equally, in the Arctic and Mediterranean, convoys formed major naval operations in their own right. Chapter 5 concentrates on amphibious warfare, the means by which the Allies planned to invade Nazi-occupied territory in Europe and the Mediterranean, and which also proved important in the Far East, especially for the Royal Marines. As the chapter demonstrates, Operation Neptune, the naval component of D-Day, was predominantly a Royal Navy affair. Yet when the war started, the Navy lacked the men, craft and doctrine necessary to prosecute large-scale amphibious operations. This capability had to be built up during the war, and was heavily reliant on RNVR officers and HO personnel, many of whom manned landing craft and did not necessarily have any natural aptitude as sailors.