THE BRITISH SAILOR OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR

Quintin Colville

Boy Seaman John Travers Cornwell, who was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for his courage in action on board HMS Chester at the Battle of Jutland, oil on canvas by Ambrose McEvoy. (BHC2635: on loan from Mrs Mona McEvoy)

Lower-deck sailors from HMS Kent striking a warlike pose, c. 1914. (WHR/2/45)

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I F YOU HAD been observing the Royal Navys ships in the opening days of the First World War you might have witnessed a curious sight. Whether at a British anchorage, or around the world from Gibraltar to Bermuda, some of the first casualties of the conflict were pianos. Already battered by rowdy evenings in the mess, and with hammers sticky from spilled beer, they were removed from gunrooms and wardrooms and either landed or unceremoniously pitched over the side. With them went assorted furniture and woodwork, comfortably domestic fittings and fixtures being considered a fire hazard if a ship was hit in combat, and also suddenly seeming rather out of keeping with the momentous news of war. This is not to say that the Navy roughed it in the years that followed. Most flag officers continued to boast day and dining cabins stocked with mahogany and silver. But these Spartan preparations reflected the reality that, after a century of relatively untroubled British sea power, the Royal Navy was facing a new European struggle and a stern test of its mettle.

Accounts and commemorations of the conflict are understandably dominated by the appalling slaughter on the Western Front. The armys loss of life has a horrifying arithmetic that the war at sea cannot match. The cultural outpouring that began with the war poets and continues to this day through novels, films and documentaries has also familiarised us with the stock characters of trench warfare: the stoical Tommy; the well-bred young lieutenant, revolver in hand; and the well-fed general enjoying the comforts of a chteau far behind the lines. For all their partiality and inaccuracy, these caricatures at least give us a point of entry to the experiences of the land war. The case of the Navy is quite different. Public memory of the hundreds of thousands of men and women who served within its ranks is, by comparison, blurred and vague. Who they were, what they did, and what contribution they made, are questions that most would find hard to answer.

Masters of the Seas, oil on canvas by W. L. Wyllie. The leading battleship, HMS Audacious, had already been sunk when this painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1915. (BHC4167)

The aim of this book is to bring these Royal Naval lives into sharper focus. It cannot attempt to explore the immensely important role played by merchant mariners, or indeed by non-British sailors from around the world. The range of naval contexts that this involves remains extraordinarily diverse from the mighty steel battleships that clashed at Jutland in 1916, to shallow-draft gunboats patrolling the inland waterways of what is now Iraq during the Mesopotamia campaign. What follows is also careful to show that the naval war did not simply take place on the waves. Although largely untried weapons at the beginning of the conflict, Royal Navy submarines soon proved their value, growing rapidly in size, seaworthiness and endurance. Even the sky was a naval battleground. For Royal Naval Air Service pilots, naval war was waged at the limits of technology and with tactics and equipment that evolved with dizzying speed. Moreover, tens of thousands of sailors fought ashore as part of the Royal Naval Division: from Belgium in 1914 to Gallipoli in 1915, and from there to the killing fields of France.

Crew of the battleship Queen Elizabeth assembled for a visit by the Bishop of London in July 1916. (N16562: Howe Collection)

The maritime struggle that involved this vast and varied cast of characters was truly global, raging from the North Sea to South America, and from Africa to China. The stakes could not have been higher. Britains war effort depended on food and raw materials from overseas crucial supplies that could only arrive by ship. Without sea power, rations and reinforcements could not have reached the men in the trenches, and the hundreds of thousands who fought alongside them from India, Australia, New Zealand, the Caribbean, Africa and Canada would never have arrived at all. From the first day of the war the German navy threatened these lifelines, and the men and women who defended them deserve a prominent place within the contemplation and commemoration of these centenary years.

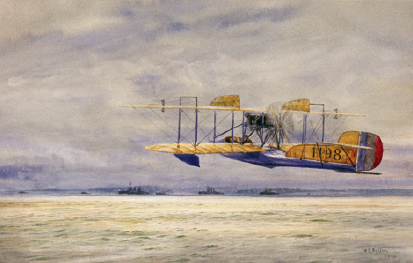

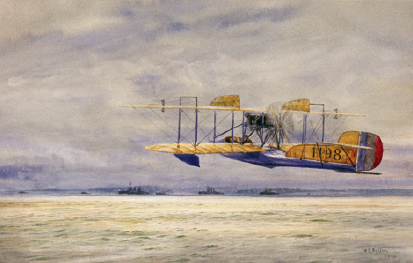

Royal Naval Air Service flying boat, watercolour by W. L. Wyllie, 1916. (PAF1860)

V Beach, Cape Helles, 25 April 1915, watercolour depicting the terrible casualties suffered during the Gallipoli landings, by W. L. Wyllie, c. 1915. (PAE0974)

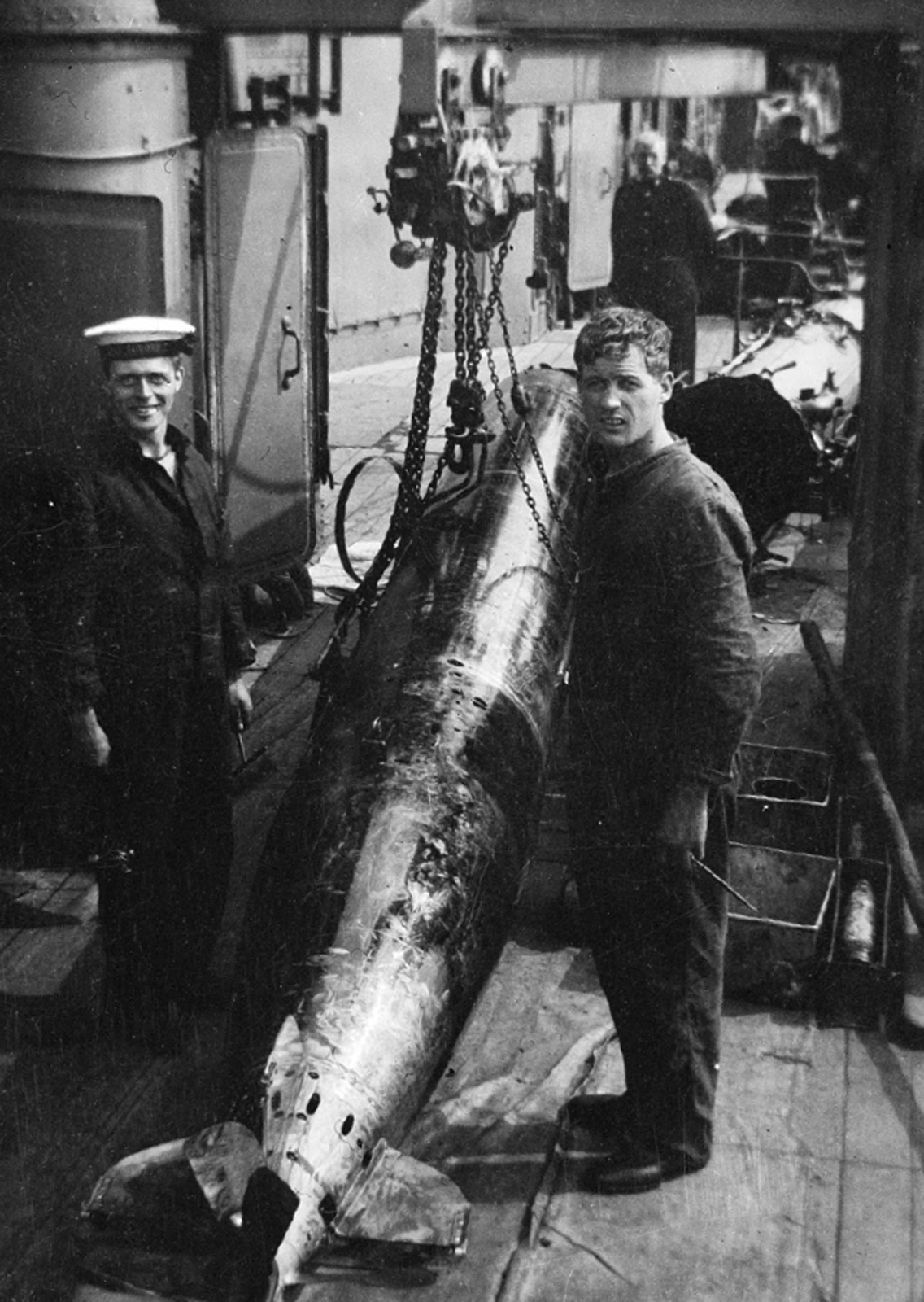

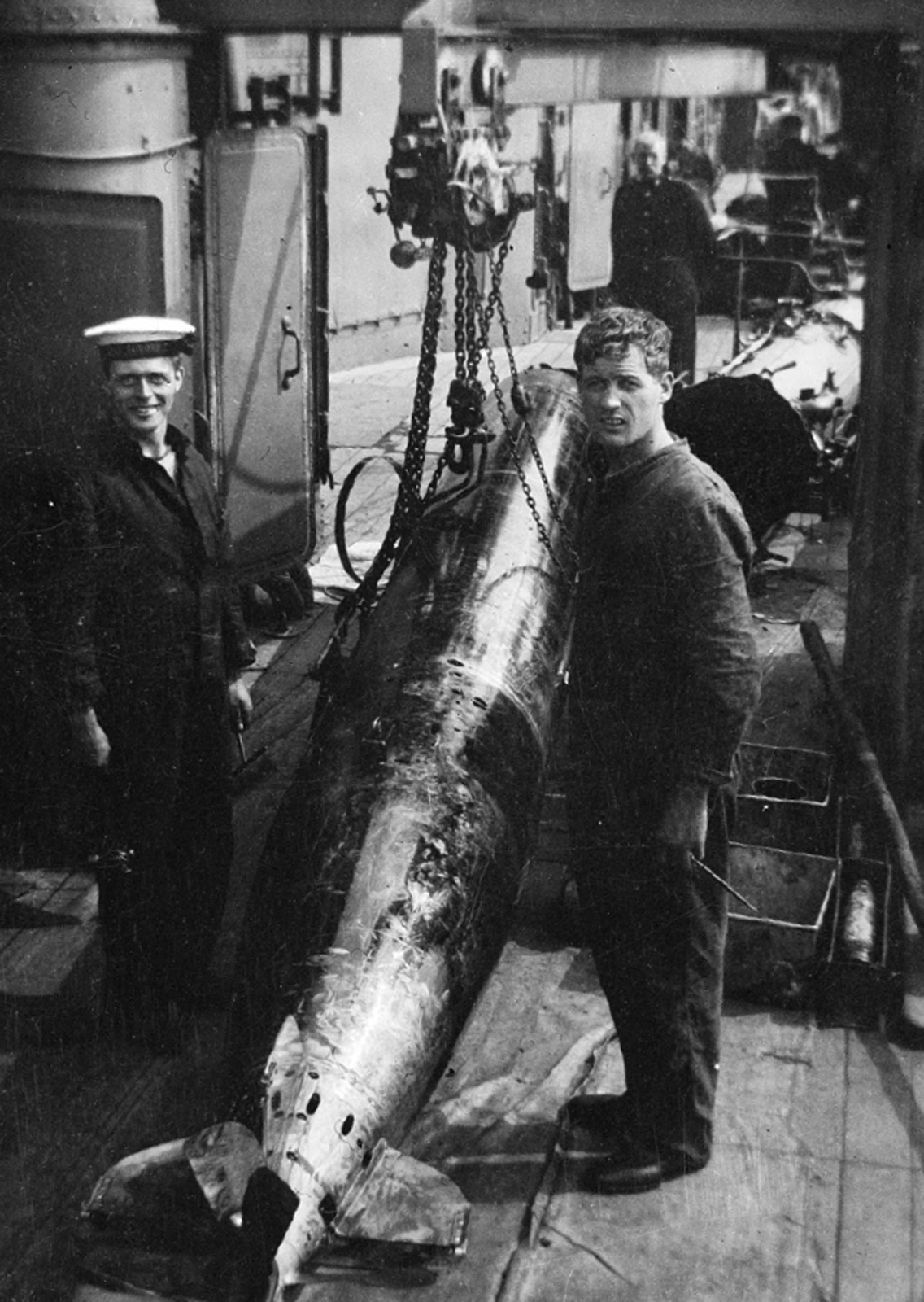

A torpedo slung from a hoist on board the cruiser Aurora, 1915. (N22862: Captain Gunn Collection)

1914: THE ROYAL NAVY AND ITS SAILORS

T HE R OYAL N AVY was a vast and intricate tool designed to further British interests in peace and war. At the same time, it was home to the men who worked, ate, slept and took their recreation within the environments it created. The living conditions that the Navy offered were as varied as the institutional tasks it faced. Sailors in the tropics sweated in airless messes with condensation dripping from the cork-lined deckheads, while their comrades in a North Atlantic gale froze in sodden clothing with a foot of icy seawater surging back and forth beneath their hammocks. Equally, the punctilious routines of a stately battleship were quite different from the more casual atmosphere of a destroyer or submarine. Even on board the same vessel, every gradation of rank and role from boy seaman to admiral represented a separate microcosm of identity, behaviour and responsibility.

However, notwithstanding this complexity, some broad generalisations can be made about the Royal Navys personnel. The first is that this was an organisation profoundly shaped by the class divisions of wider British society. From the later Victorian era to the middle of the twentieth century and beyond, the great majority of naval officers were the sons of upper-middle-class civil servants, doctors, lawyers, clergy, bankers and businessmen. To their parents, a career in the senior service promised some financial security, a clearly defined ladder of promotion, and above all membership of a solidly respectable and gentlemanly profession. Moreover, it was a commonly held view of the time that only boys from this end of the social spectrum were likely to possess the discipline, self-control and command ability that the Navy required in its leaders. These realities were laid bare in the training the Navy provided for its youthful officer material. Opened in 1905, and built in splendour on the heights above Dartmouth, Britannia Royal Naval College was essentially a naval public school, charging fees that no working-class family could possibly afford.

Next page