Acknowledgements

Ian Buxtons book Big Gun Monitors gives an excellent detailed account of the construction and deployment of the monitors, and particularly of their main armament.

Severns Saga by E. Keble Chatterton is a most interesting account of operations in East Africa.

The Dover Patrol (Two Volumes) by Sir Reginald Bacon, The Keyes Papers (Two Volumes), and Roger Keyess Naval Memoirs give a good insight into the bombardment of the Belgian Coast. Keyes also gives an interesting if rather one sided account of the Dardanelles campaign.

Castles of Steel by Robert Massie is an excellent general account of naval affairs during the First World War and Engage the Enemy More Closely by Correlli Barnet is an excellent history of the Royal Navy in the Second World War.

D-Day by Anthony Beevor is a first class account of the Normandy landings.

Walcheren 1944 by Richard Brooks is an excellent source of information on this action.

Battleship by H.P. Wilmott is an excellent exposition of the evolution and use of battleships.

There are many other useful source books including Corbett, Madden and Jellicoe on the First World War and Roskill on the Second World War.

Photographs by permission of the Imperial War Museum.

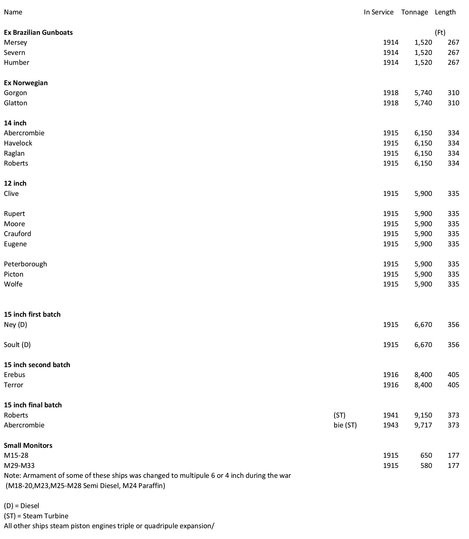

Appendix

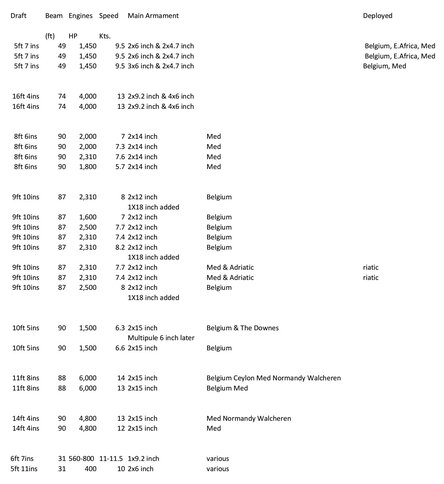

List of British Monitors 1914 - 1945

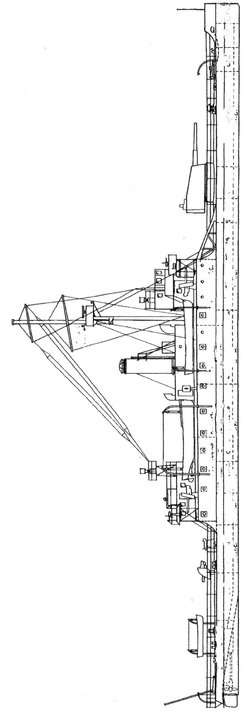

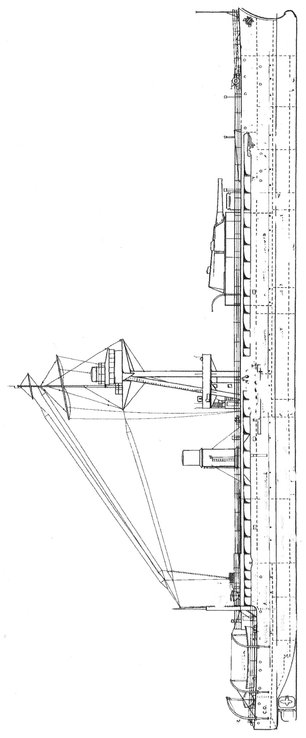

1 Severn

When she was launched Severn had the twin 6 inch turret shown here, it was replaced by two single turrets when the first set of guns were worn out after the Belgian Coast operation. Note the very low profile of the hull and the propellers mounted in a tunnel so as to reduce draft.

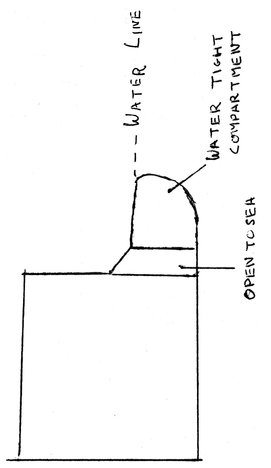

2 Section of Monitor Hull

The bulges protruded well outside the hulls making boat handling extremely difficult. They did afford good protection from underwater weapons and made the ships very stable but slow.

3 A 14 inch Monitor

These ships had U.S. made turrets which were electrically operated where as all Royal Navy experience was with hydraulic operation.

4 A 12 inch Monitor.

These ships proved to have insufficient range to operate against German batteries on the Belgian coast but did good work in net defence and as guard-ships.

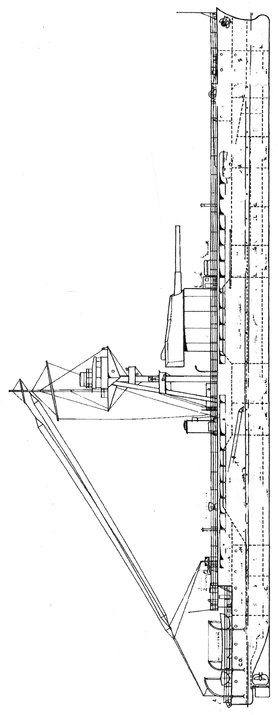

5 Ney

Ney was the least satisfactory of all the monitors as she was so unreliable and slow. The 15 inch turret had to be mounted on top of a column because of the height of the diesel engine beneath it. Her sister ship Soult did some good service. Note the short funnel required by the diesel engine.

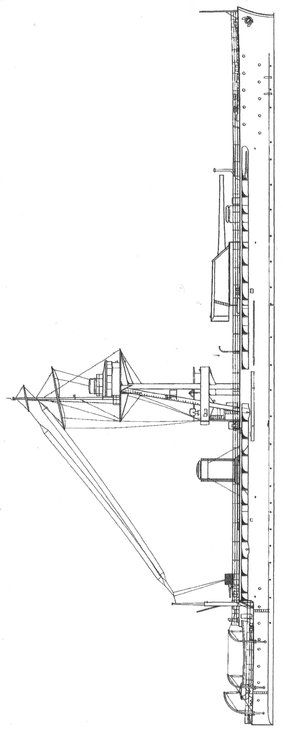

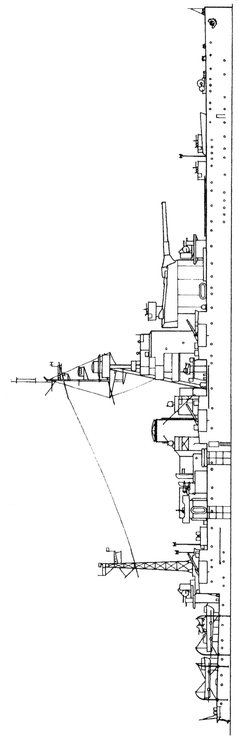

6 Erebus in 1944

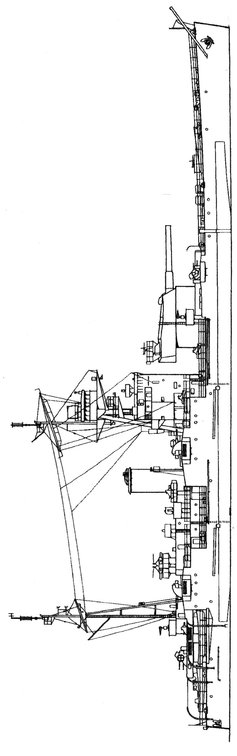

Compare the line drawing to photograph no. 6 showing Erebus before radar and extra anti-aircraft guns were added. All the extra "clutter" aft made her even more difficult to steer than when she was new. Bacon suugested that she should be fitted with a rudder at the bow so that she could back away from the Belgian coast whilst still using her main armament, but this was never fitted. Note that she has a proper bridge instead of the conning tower fitted to earlier monitors. In a following wind the smoke from the funnel would envelop the bridge to the great annoyance of the watchkeepers.

7 A 9.2 inch Small Monitor

These were most useful little ships, cheap to build and operate and moderately sea worthy. They gave excellent service in many theatres.

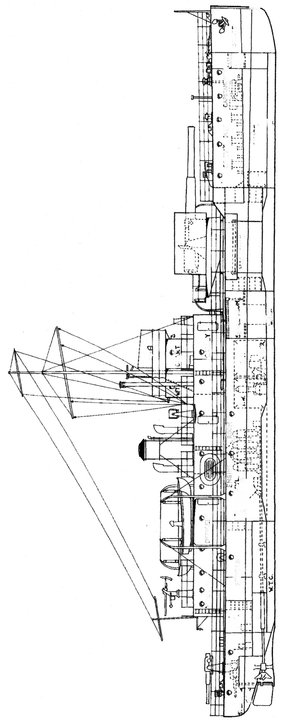

8 Abercrombie

Abercombie was the last monitor to be built, she spent most of her active life supporting American troops who nicknamed her "Little Dumbo". Note that her bulge now protrudes above the water line which made boat handling much easier. She was fitted with the most up to date radar and fire control equipment as can be seen from the drawing.

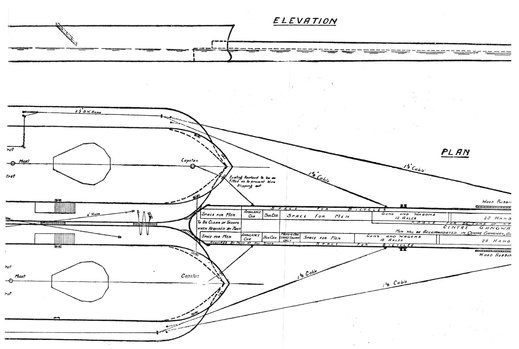

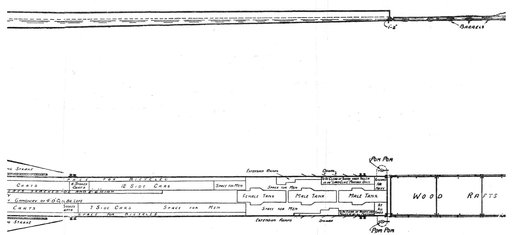

10 Diagram of Monitors and Pontoons for the Great Landing Two 12 inch monitors would push each of the three pontoons fully loaded with men, tanks and equipment. The raft in the bows would run onto the beach against the sea wall to allow men and tanks to get ashore, covered by fire from the monitors.

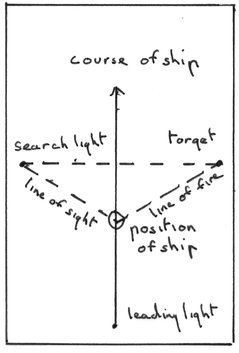

9 System for Night Firing

A ship steaming on a known course at a known range from the target would train its director on a searchlight in a position roughly opposite to the target and fire in the reverse direction to that indicated by the director.

Chapter 1

Origins

I n the 1690s an entirely new class of warship caused consternation and a crisis of conscience to the English ruling classes. The offender was the bomb ketch, a vessel copied from the French. Bomb ketches were small, shallow draft ships, able to get close inshore. They were armed with a dastardly weapon, a large bore mortar, which threw an explosive bomb far up in the air so that it cleared the walls of waterside cities or harbours and exploded when it struck the ground, damaging property and killing soldiers and civilians alike. The British used them thus to bombard St Malo, Le Havre, Dieppe and Dunkirk. John Evelyn, the diarist, wrote that the Navy should be employed to protect British shipping not Spending their time bombing and ruining a few paltry little towns... a hostility totally averse to humanity and especially to Christianity, however the bomb vessels, Christian or otherwise, continued to be developed and used. They fought the French off Gibraltar, where in a flat calm they engaged and severely damaged some French ships of the line, and at Toulon, where the fire from English and Dutch bombs destroyed several ships in harbour and caused the French to panic and scuttle the remains of their battle fleet at its moorings. This was a particularly significant action in that the Allies had landed observers ashore to watch the fall of shot and signal corrections to the gun layers afloat. This practice became frequently used when bomb vessels were employed, and a special force of observers were trained and retained by the Ordinance Board to undertake these duties. They would go to sea in tenders, one of which was attached to each bomb vessel to accommodate them and to carry spare ammunition.