Richard Woodman - The Merchant Navy

Here you can read online Richard Woodman - The Merchant Navy full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Shire, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Merchant Navy

- Author:

- Publisher:Shire

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Merchant Navy: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Merchant Navy" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Merchant Navy — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Merchant Navy" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Richard Woodman

A British poster of the Second World War expressing the nations gratitude to the Merchant Navy for delivering food and vital supplies. Two merchant seamen fire an anti-aircraft gun during the Battle of the Atlantic. In the background flies the red ensign the flag of the Merchant Navy.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

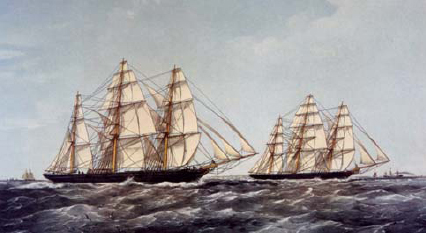

The famous clipper race, between the Ariel and Taeping in 1866, bringing back tea from China to London. Clippers were built for speed and before the opening of the Suez Canal there was an annual clipper race. The winners earned a bonus for the first tea cargo delivered.

Tudor sailors like this, most likely civilian crewmen for merchant vessels, often found themselves involved in sea battles as England and Spain fought for control of the great Atlantic sea routes.

M ARITIME NATIONS are defined by their possession of a navy and a mercantile marine, the first consisting of their armed ships of war, the second of privately owned vessels that carry cargoes for profit either in the national interest, as imports and exports, or on behalf of others. Such national commercial fleets are commonly referred to as a mercantile marine, but in Britain it is known as the Merchant Navy as a result of its importance and extraordinary sacrifice in the First World War. This was repeated between 1939 and 1945 when the integration of merchant shipping with the armed forces was so close that it did, in fact, become a second navy, all ships being armed. The ships of national mercantile marines wear the maritime ensign of the country in which they are registered and by which they are regulated; the ships of the British Merchant Navy wear the red ensign. Although initially also a naval ensign, an Act of Parliament in 1864 had made this the exclusive flag of privately owned British vessels.

Historically, the private ownership of vessels has been vested in a wide range of commercial entities. Some possessed no more than perhaps one or two vessels of a single type; others comprised huge and complex conglomerates with scores of ships designed with different purposes in mind and trading all over the globe under a variety of company names. Today the British Merchant Navy includes not only ships owned by British citizens, but also those placed by their owners under British regulation under the Tonnage Tax regime. This entitles them to wear the red ensign of Great Britain and, in exchange for certain undertakings (chief of which is the training of young seafarers) to receive tax breaks. British registry implies their owners sign-up to certain audited practices, which range from safety and maintenance standards to the protection of the environment through on-board regulation. This assurance of quality allows an owner of a British registered ship to be placed on the so-called white list of national registers, making his vessels more attractive to those seeking safe and profitable delivery of their cargoes. Owning a British-registered vessel also guarantees the protection of the Royal Navy in troubled times.

The origins of both the British Merchant and Royal Navies lie in the first half of the sixteenth century when, under Henry VIII, England in particular began to flex her muscles as a potential maritime power. There had been an early medieval trade with western France (then mostly fiefdoms of the Norman kings of England), wine being the most important import. It was loaded in Bordeaux in large casks, or tuns, from which we derive the expression for describing a ships capacity, or burthen. This system of measurement facilitated both the levying of the kings customs duties and the value of a vessel when requisitioned for war. Growing exports of English wool for manufacture into cloth in Flanders encouraged trade on the east coast of England, but much commerce at the time was borne not in English ships but in those of the Hanseatic League a confederation of the mercantile associations of port-states in what is now modern Germany which established commercial bases in places as far apart as Bergen (in Norway) and London. These easterlings became renowned for their straight-dealing, from which is derived the word sterling as a mark of the soundness of the British national currency. With much of our trade in the hands of foreigners, there was little call for any major home-grown enterprise until the reign of Richard II (137799), when this became a political issue. In 1381 the first Navigation Act forbade the export of cargo in anything other than an English vessel, encouraging the growth of small ship-owning syndicates of English merchants.

Merchant ships during the reign of Edward IV in the late fifteenth century. The first Navigation Act of 1381 had already forbidden the export of cargo in anything other than an English vessel, encouraging the growth of privately owned merchant ships.

Besides the wine and wool trades, English, Irish, Welsh and Scottish coastal communities had begun to extend their fishing further offshore. Meanwhile, coal began to be mined in the north-east of England, which answered a demand being created in the slow but steady expansion of London; this created a coastal coal trade that would last until the second half of the twentieth century. Despite all this, English commercial shipping remained limited in its ambitions, largely coastal or cross-Channel, extended further only by overseas military adventures. The English and Scots remained island peoples, their kings fighting each other and feuding with their nobles, their respective homelands being regarded by much of Europe as ultima Thule.

It was not until the dynastic Wars of the Roses finally ended in 1485 that the incoming Tudors offered England the conditions under which the initiative of its merchants might truly prosper. By this time there were rumours of far-off countries of fabulous wealth. Hearing of Columbuss discoveries in 1492, and encouraged by Londons merchants, Henry VII employed the Genoese navigator Giovanni Caboto (John Cabotto) to discover a territory in this New World for England. In 1486 Cabot laid claim to what he called Newfoundland and, on their homeward voyage, Cabot and his crew aboard the Matthew came across the cod-rich waters of the Grand Bank. From this point Englishmen began to look to seaward to make their fortunes while simultaneously competing with the Portuguese, who also fished the Grand Bank.

Yorkshire-born Sir Martin Frobisher was a merchant venturer who explored the possibility of a north-west passage for trade to China for the Company of Cathay in 1577. Here, he encounters hostile Inuit.

Henry VIII succeeded his father in 1509; he was young and ambitious. His break with Rome over his divorce from Catherine of Aragon brought England into conflict with a Catholic Europe, itself riven by the new Protestantism. Fired by an energetic zeal purporting to be Protestant but not unmixed with envy and opportunism, an increasing number of young men went to sea in search of plunder. They actively defied the Papal decree that divided the world between the dominant maritime nations of Spain and Portugal. Riches poured into the coffers of Madrid and Lisbon, largely from the import of silver from Peru and the highly prized spices from islands in the distant east. To an aggressive Protestant state the Papal ruling was a challenge and English mariners and their backers sought to break this cartel. These merchant venturers came chiefly from the emerging middle class but were joined by a small number of aristocrats. Chiefly based in Bristol and London, these syndicates sent out speculative trading expeditions financed by joint stock companies, which avoided direct confrontation with the predominating maritime powers by attempting to out-flank them. One tried to find a route to the Spice Islands to take advantage of the high prices commanded by nutmeg in particular, but the chosen route to the Orient, north of Russia and through the north-east passage, was barred by ice. The first voyage commanded by Sir Hugh Willoughby ended in disaster in 1554, notwithstanding which the Muscovy Company opened a profitable trade with Russia. Joined by the Levant Company, which concentrated on trade with the eastern Mediterranean, these two joint stock companies laid the foundation of regular English overseas commerce in English ships, the latter founding overseas consulates. Attempts to reach the east by way of the north-west passage, though preoccupying explorers for far too long, also ended in disaster but, in the final years of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (who secretly invested in the enterprise), a group of London merchants and investors were granted a royal charter incorporating them as the East India Company. It was thi commercial venture, led by James Lancaster, which laid the foundations of the British Raj in India.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Merchant Navy»

Look at similar books to The Merchant Navy. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Merchant Navy and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.