Bismarck

the Epic Chase

Bismarck

the Epic Chase

by

Jim Crossley

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by

Pen & Sword Maritime

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Jim Crossley 2010

ISBN: 978-1-84884-250-2

The right of Jim Crossley to be identified as Author of this Work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13pt Palatino by

Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire

Printed and bound in England by

the MPG Books Group

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe

Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and

Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Strategic Situation May 1941

Britain Stands Alone

Just after 11 a.m. on 18 May 1941 two massive grey shapes slipped out of the harbour of Gotenhafen (now called Gdynia) and dropped anchor in the outer roads. They were the battleship Bismarck, the most formidable warship in the world, and a powerful heavy cruiser, Prinz Eugen. They were embarking on an enterprise which was to be endowed with all the foreboding, tragedy and suspense of the most melodramatic of Wagnerian operas, leaving two of the biggest warships in the world at the bottom of the sea, with over 4,000 seamen alongside them. All this action was compressed into a period of less than ten days. It was to be a contest in which technology, luck, seamanship, airmanship and old-fashioned human grit all played a part. To understand it fully we must start by reviewing briefly the strategic situation as it existed in May 1941.

Germany had crushed the Polish forces in 1939, and Hitlers cynical pact with Stalin had allowed the division of that unfortunate country between two ruthless regimes of unparalleled savagery. Holland, Belgium and Denmark had been subdued without too much difficulty, and Norway, with its rich mineral resources, vital to the German war effort, had fallen to a brilliantly planned and executed naval and military campaign. The countries of central Europe had been recruited or dragooned onto the Axis side. Last of all, in summer 1940 France had fallen to a devastating armoured and airborne assault, destroying her own army and sending the British forces in France scrambling desperately home, leaving their arms and many of their colleagues behind them. Germany was checked at the Channel, where the Luftwaffe was unable to establish the air superiority needed to allow German armies to force a crossing, so for the time being the land war in the West was suspended. For Germany this was not a significant check. Hitler himself was not really committed to an invasion of Britain at this point. He had other fish to fry. As the onset of autumn weather and the valour of the RAF aircrews brought a halt to the intense daytime bombing raids on southern England, his air fleets and Panzer armies redeployed in readiness for a devastating assault planned for summer 1941. This was to be against his erstwhile partner in crime the Soviet Union.

A more active theatre of conflict for Britain now emerged in the Mediterranean. It was vital for her to retain control of the Suez Canal and of Egypt. Italian forces in Libya and Ethiopia threatened both. The Italians had at first been fairly easily defeated, but in 1941 Rommel arrived on the scene with his superb Afrika Korps, supported by modern aircraft. Before long, British forces were pushed back and the desperate siege of Tobruk commenced, tying down a large part of the British army, and the ships and aircraft required to supply them. The Germans also pulled Italys chestnuts out of the fire in Greece, where local fighters had held up and indeed reversed Italian advances. The appearance of German forces in support of the Italians rapidly turned the tables. Churchill unwisely diverted the efforts of the forces facing Rommel in Egypt to support the Greek cause, and the result was a crushing defeat for Britain and the Greek patriots. In May, at the same time that Bismarcks voyage was in progress, German forces had thrown the British out of mainland Greece altogether and were overrunning Crete, forcing a British withdrawal from the island, which was accomplished a few days later with heavy losses of men and material. In particular, total lack of air cover for the ships evacuating the troops resulted in disastrous losses for the British Mediterranean Fleet. Here, as everywhere, it seemed, Hitlers forces were triumphant.

It was not in Greece or in north Africa, however, that Germany presented the most deadly threat to Britain. Depending on international trade routes to supply her with arms, raw material, food and troops from her Empire, Britain was at the mercy of any enemy who could challenge her navy and close her vital, sea lanes. This had very nearly happened in 1917, when U-boats had brought the country to within a few weeks of running out of food. Then only the diversion of the bulk of the destroyer force from guarding the Grand Fleet and the deployment of the little ships as escorts for convoys saved the country from being forced to sue for an ignoble peace. In 1941 it seemed that in spite of the convoy system there might be no way of averting a similar disaster.

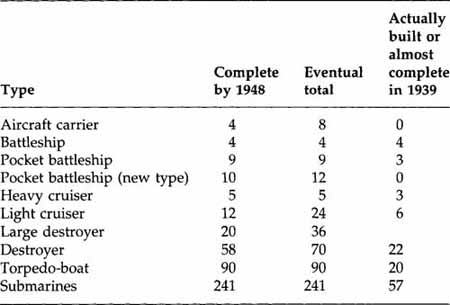

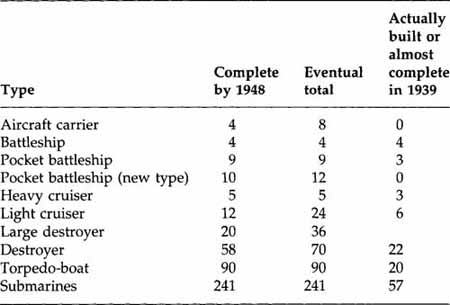

It was not that Germany had been getting all her own way at sea. In the years leading up to the war, Germany had begun to develop a powerful surface navy, intended to be strong enough to take on that part of the Royal Navy likely to be stationed in home waters during hostilities. The naval building programme was set out in Plan Z. It called for the following fleet to be built:

As shown in the third column, the number of ships actually built fell far short of the plan, and left Germany with an unbalanced fleet. There were two reasons for this. Firstly Hitler had completely miscalculated the reaction of Britain and France to his invasion of Poland. He had actually promised Admiral Raeder, the chief of his navy, that there was no question of a war with Britain until 1945 at the earliest. Indeed he actually apologised to the admiral for the fact that his plans had gone wrong soon after the outbreak of the war. Secondly, as soon as war broke out the whole warship-building programme was suspended, and the labour and materials that had been allocated to surface ships were diverted to other projects. Only the U-boat programme remained intact. This left numerous half-built hulls on the stocks, notably the carrier Graf Zeppelin and the cruisers Seydlitz and Lutzow (which was later sold to Russia). Raeder, who had a difficult relationship with Hitler, had to make do with what ships he had. (A brief description of the organisation of the

Next page