THE VICTORIA CROSS AT SEA

The Sailors, Marines and Airmen awarded Britains Highest Honour

This edition published in 2016 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

First published by Michael Joseph Ltd., London, 1978.

Copyright John Winton, 1978

The right of John Winton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-47387-612-5

PDF ISBN: 978-1-47387-615-6

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-47387-614-9

PRC ISBN: 978-1-47387-613-2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please visit

or write to us at the above address.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in 10.5/12.5 point Palatino

For more information on our books, please email: ,

write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

Introduction

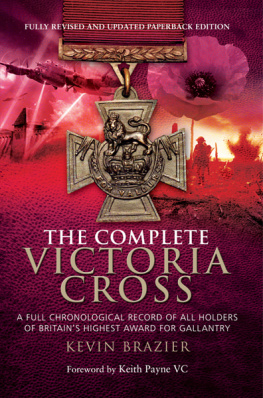

M ost of this book is true. Some of it is very probably true, and part of it is possibly myth. The Victoria Cross is still so emotive, romantic and controversial a subject that it is often difficult to separate fact from fiction. The Victoria Cross still arouses fierce national, county, local and family pride, generates frantic newspaper correspondence, sets regiment against regiment, unit against unit. Everybody is an expert on the Victoria Cross. Everybody has met a winner, or is related to, or has served with, or lived next door to, a winner, or has been to a school, won a prize, drunk beer in a pub, named after a winner. In such a heated atmosphere, hearsay can quickly become received fact, speculation can become tradition, and gossip become gospel. An unchecked newspaper cutting, with wholly imaginary information, can become accepted research material for generations afterwards. The awards themselves depended in the first place upon eyewitness accounts, notoriously subjective sources, especially when clouded by the fog of war. Some citations, especially the earlier ones, are so laconic as to be almost meaningless. No citation can be taken as entirely reliable, and one at least (Hallidays) was actually challenged later by the winner himself! Any writer on the Victoria Cross has ultimately to strike his own balance of truth.

The Victoria Cross was Queen Victorias own idea. She realised, as the preamble to the original Royal Warrant of 29th January 1856 stated, that there was no way of adequately rewarding the individual gallant services either of officers of the lower grades in Our naval and military service, or of warrant and petty officers, seaman and marines in Our navy, and non-commissioned officers and soldiers in Our army. In other words, from its inception the Victoria Cross was a medal for everyman. All persons were on a perfectly equal footing neither rank, nor long service, nor wounds, nor any other circumstance or condition whatsoever, save the merit of conspicuous bravery would qualify a man for the VC. It was not an Order of Chivalry like the Garter or the Bath. It was open to any officer or man who served the Queen in the presence of the enemy and then performed some signal act of valour or devotion to his country. The Queen desired that the medal should be highly prized and eagerly sought after.

Victoria took a keen interest in every aspect of the Cross and personally supervised the design, the wording, the size and the material of which it was made. On 5th January 1856, a communication from Windsor Castle to the then Secretary of State for War said: The Queen returns the drawings for the Victoria Cross. She has marked the one she approves of with an X; she thinks, however, that it might be a trifle smaller. The motto would be better For Valour than For the Brave, as this would lead to the inference that only those are deemed brave who have got the Victoria Cross. The design the Queen chose was a cross patt, very similar to and often called a Maltese Cross, attached by a V to a bar on which is a sprig of laurel. Obverse, a Royal Crown surmounted by a lion with a scroll underneath bearing the words For Valour. Reverse, plain, with an indented circle in the centre, with the date or dates of the act of valour inscribed in it. The name of the winner is engraved along the back of the bar.

The cross itself was not of silver or gold, or encrusted with precious stones, but intrinsically almost worthless, being cast in bronze cut from the cascables (the round pieces at the end of the barrels) of Russian cannons captured at Sebastopol in the Crimean War. The medals, traditionally always made by the same firm, Hancocks, hung on ribbon 1 inches wide, red for Army winners, blue for the Navy. When the RAF became a separate organisation on 1st April 1918 it was realised there was no really suitable colour for RAF VCs, and, as the two colours had always been somewhat unnecessary, it was decided by King George V that thenceforth all VCs would have the red ribbon. The last naval VC to have a blue ribbon was Prowse (gazetted on 30th October 1918) and the first to have a red ribbon was Beak (gazetted 15th November 1918). When the ribbon only was worn on a tunic, a miniature cross was set in its centre. For a bar, a second miniature was worn. No naval VC has won a Bar.

VC winners, except those of commissioned rank, received a pension of 10 a year, with 5 extra for a Bar. This sum remained unchanged for over a century until 1959, when Mr Harold Macmillan, replying to a question from Sir John Smyth VC, MP, announced that all VC winners, of whatever rank or rating, would receive a pension of 100 a year, tax free.

The first awards, made retrospective to cover the Russian War just ended, appeared in The London Gazette of 24th February 1857. There were 85 names in that first list, 27 of them from the Navy and the Marines. The Queen herself held the first Investiture of VCs, in Hyde Park on Friday, 26th June 1857. Of the 62 VCs invested that day, Commanders Raby, Bythesea and Burgoyne, Lieutenants Lucas and Hewett, Warrant Officers Mr Robarts, Mr Kellaway, and Mr Cooper, and Trewavas, Reeves, Curtis and Ingouville, represented the Navy. Lieutenant Dare and Bombardier Wilkinson represented the Marines. The Admiralty sent off the VCs for those naval winners serving abroad so that they could be invested on their foreign stations.

A total of 1,352 VCs have been awarded, including three Bars, to date. Of those, 124 are described in this book. They include all the Royal and Commonwealth Navy and Marine VCs won on sea, land or in the air, with four Coastal Command VCs.

The first act of gallantry to win a VC was by Mate Lucas, of HMS Hecla, in the Baltic on 21st June 1854. The first man to be gazetted was Buckley, because his name was the first alphabetically of the naval officers, who came first because they were in the Senior Service. Likewise, the first man ever to wear a VC was Commander Raby, the senior officer of the Senior Service present at the Hyde Park Investiture. The first VC awarded to a member of the lower deck was won by William Johnstone, who was not a seaman but a stoker and almost certainly not a British citizen, being very probably one of the many Scandinavians recruited into Napiers undermanned Baltic Fleet. His VC was, presumably, sent abroad.