About the Book

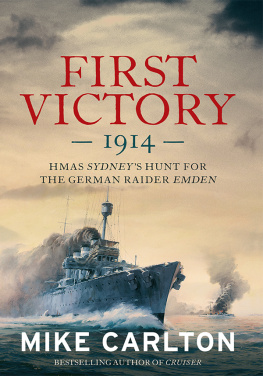

When the ships of the new Royal Australian Navy made their first grand entry into Sydney Harbour in October 1913, a young nation was at peace.

Less than a year later Australia had gone to war in what was seen as a noble fight for king, country and Empire. Thousands of young men joined up for the adventure of having a crack at the Kaiser. And indeed the German threat to Australia was real, and very near in the Pacific islands to our north, and in the Indian Ocean.

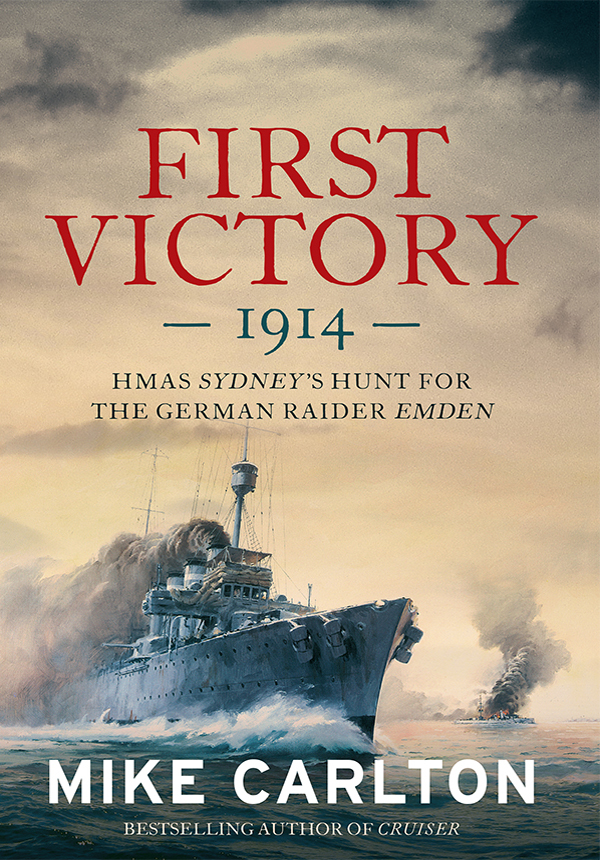

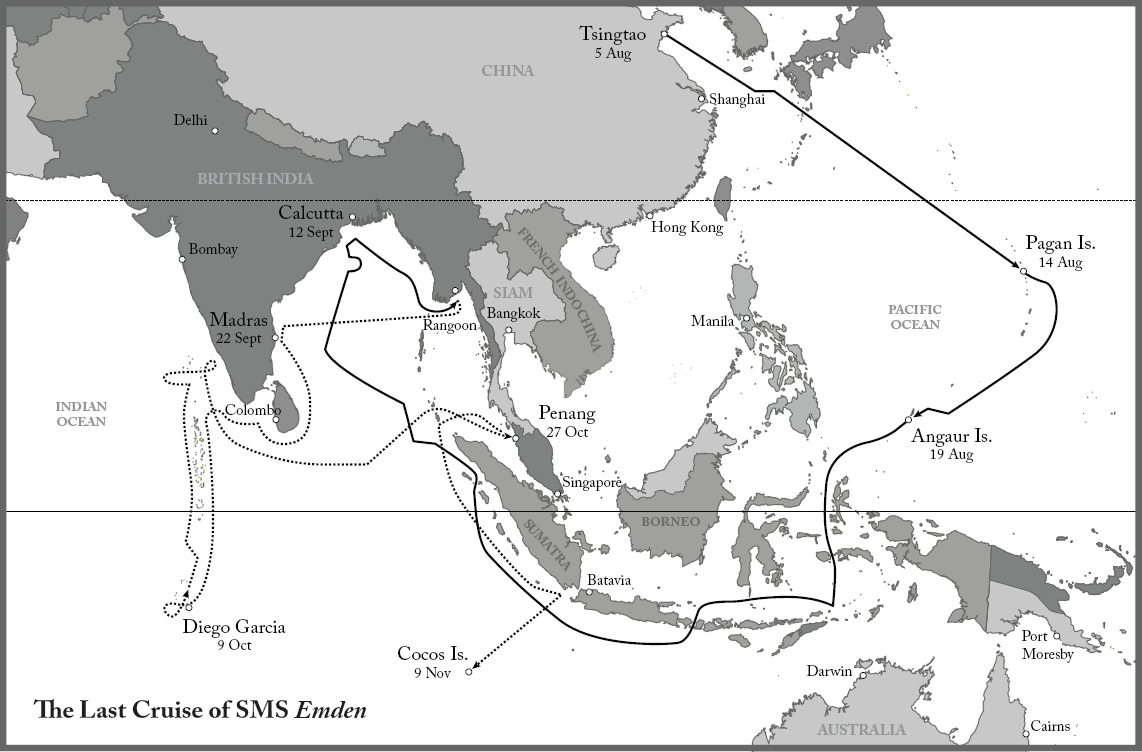

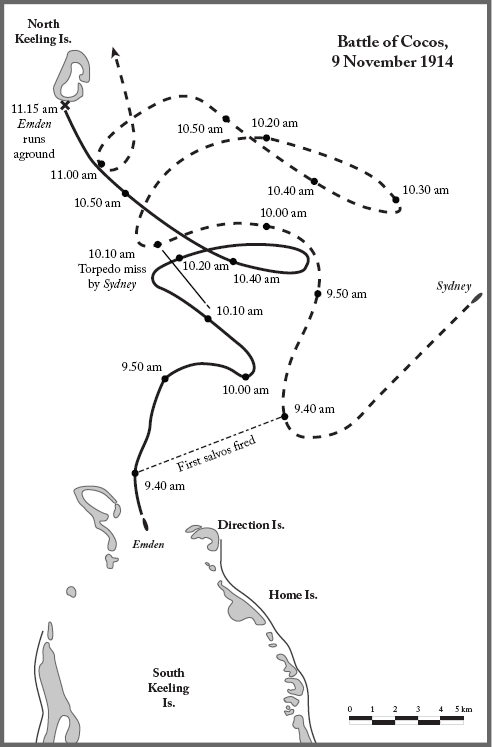

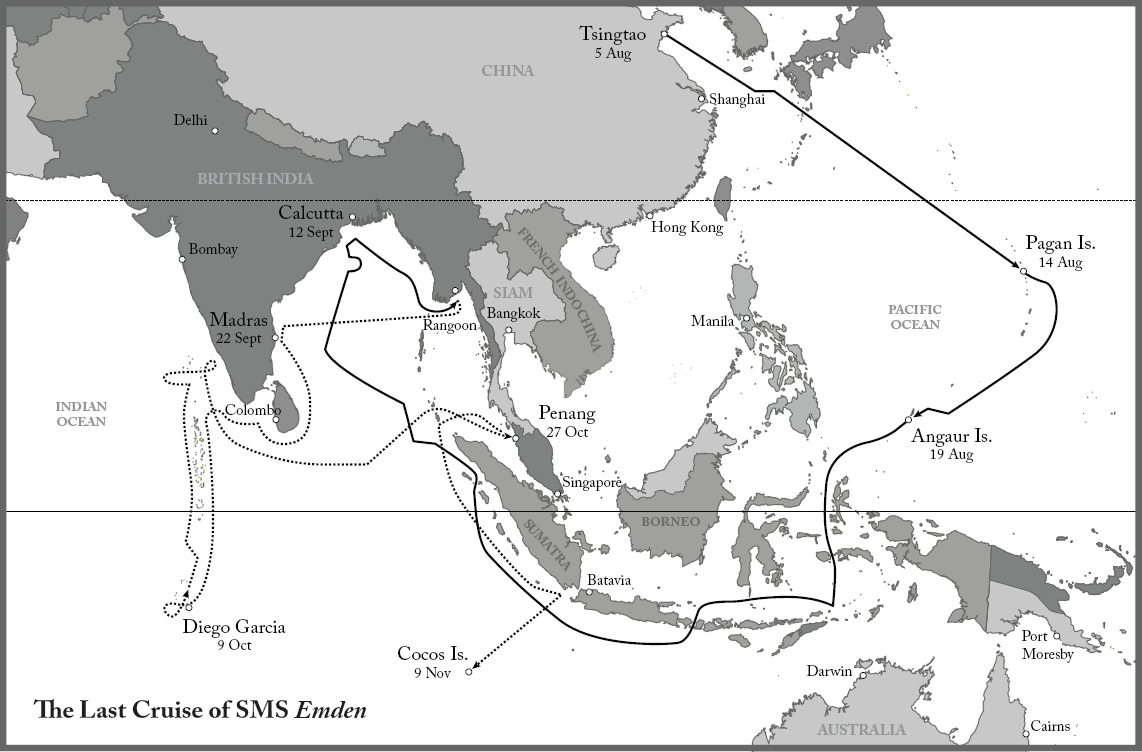

In the opening months of the war, a German raider, Emden, wreaked havoc on the maritime trade of the British Empire. Its battle against the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney, when it finally came, was short and bloody an emphatic first victory at sea for the fledgling Royal Australian Navy.

This is the stirring story of the perilous opening months of the Great War and the deadly sea battle that destroyed the Emden in a triumph for Australia that resounded around the world.

Also by Mike Carlton

Cruiser: the life and loss of HMASPerth and her crew

CONTENTS

To Lachlan Michael McInnes Carlton

FOREWORD

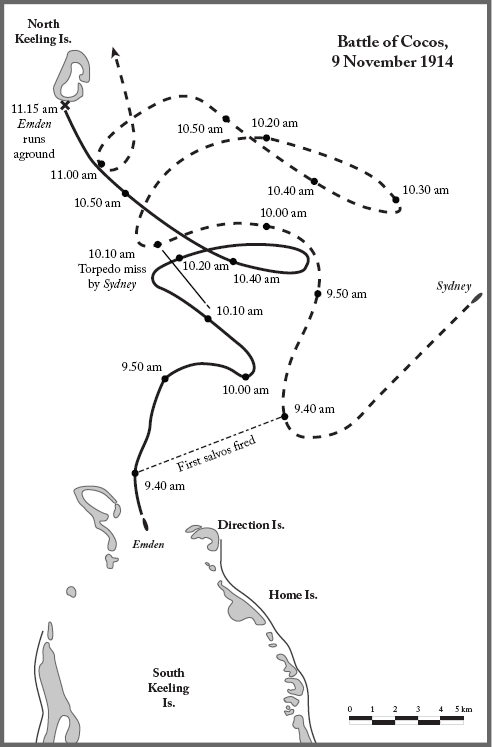

At first, I had planned to write solely an account of the sea battle between the German commerce raider SMS Emden and the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney, fought at the Cocos Islands, in the Indian Ocean, on 9 November 1914. It is an extraordinary story.

In the opening months of the First World War, Emdens trail of destruction was tremendous. This one small ship and her skilled and gallant captain wreaked havoc on the maritime trade of the British Empire, capturing and sinking ships at will. Australia, sending wool, wheat and gold across the Indian Ocean to sustain the Mother Country and despatching tens of thousands of young men to join the fight, had a vital interest in bringing Emden to her end. The battle, when it came, was short and bloody, an emphatic first victory at sea for the newborn Royal Australian Navy. It remains to this day a celebrated epic of naval warfare.

In the century since, many writers have been there before me. Most were German, some of them survivors of the battle, others later historians, and they have generally told the story well. British accounts vary in quality, from good to nonsense, and there have been some patchwork American attempts as well. Curiously, there has been very little written from an Australian point of view. This book is in part an attempt to remedy that, with new facts and perspectives brought into the light of day.

But, as I began my research in early 2012, I was struck by how ignorant I was of how and why Australia went to war in 1914. The legend of Gallipoli and the horrors of trench warfare in Europe are familiar to us all, but few Australians understand how we got there. A lot had been lost in the passage of time, I thought.

To test this theory, I began asking friends and acquaintances to name the Australian Prime Minister when war was declared, and to say what was happening in politics and parliament. Almost nobody knew the answers, including two senior Labor cabinet ministers and some prominent figures in the coalition. Even an account on the website of the Australian War Memorial gets the Prime Minister wrong. Yet this was by far the most devastating of all our wars, with 61,720 Australians killed from a population of about five million. A century on, the ignorance is lamentable.

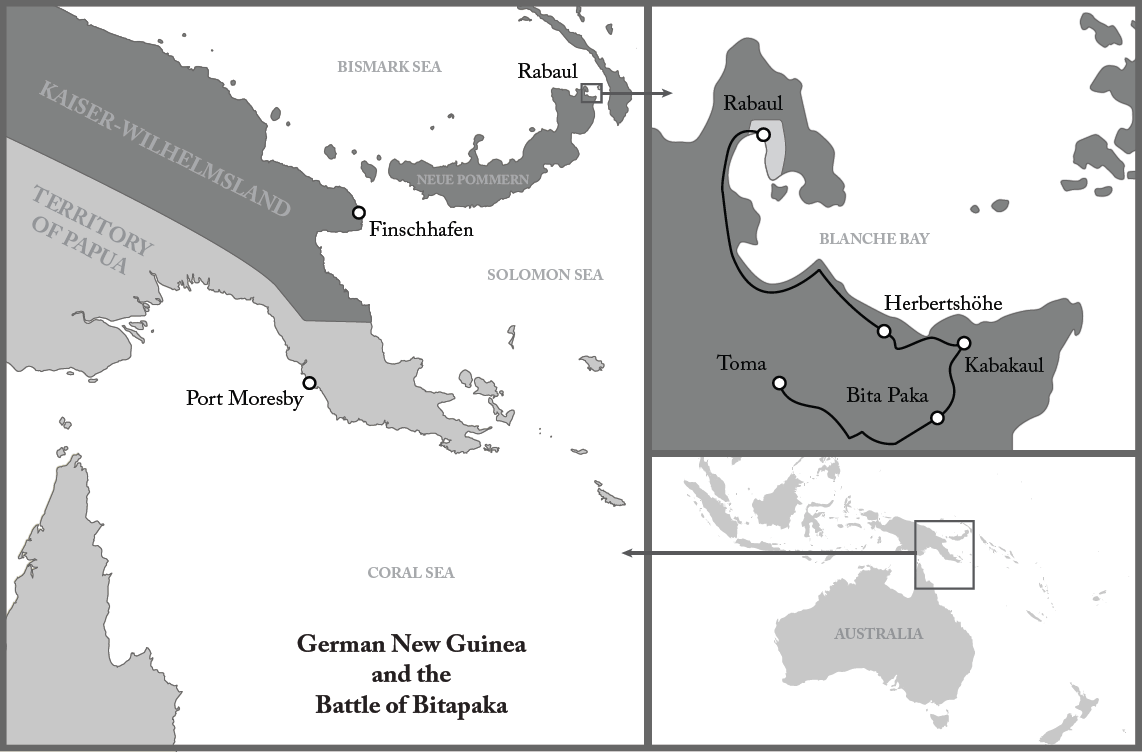

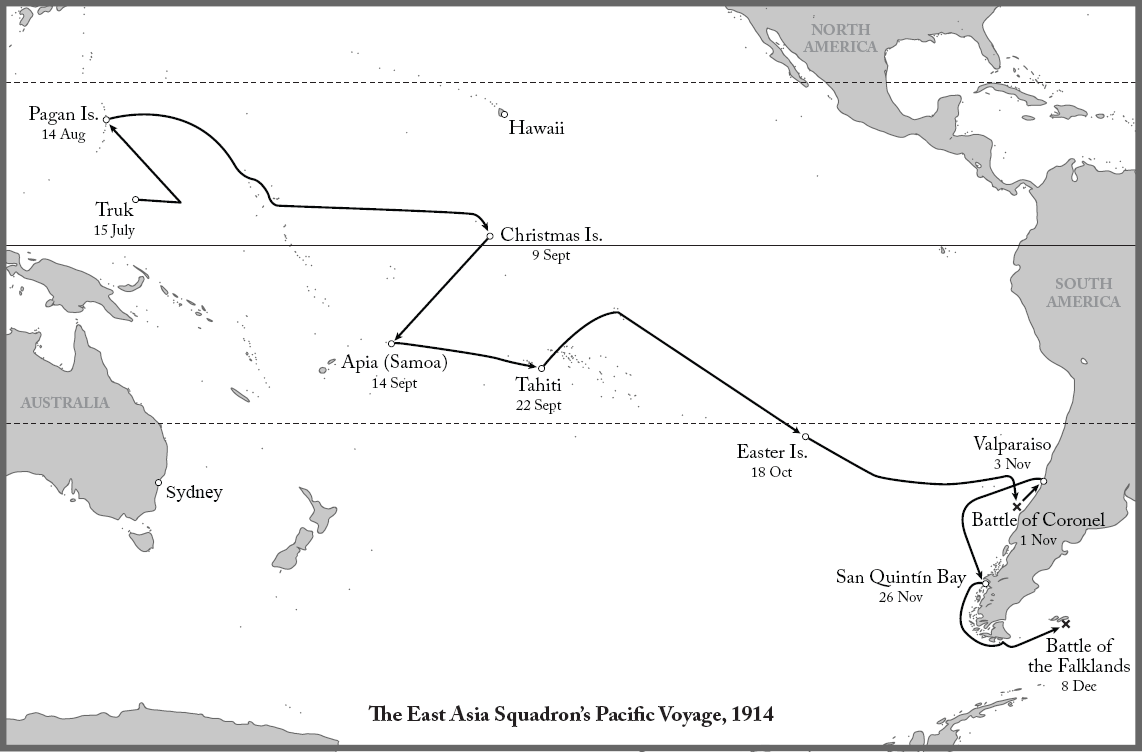

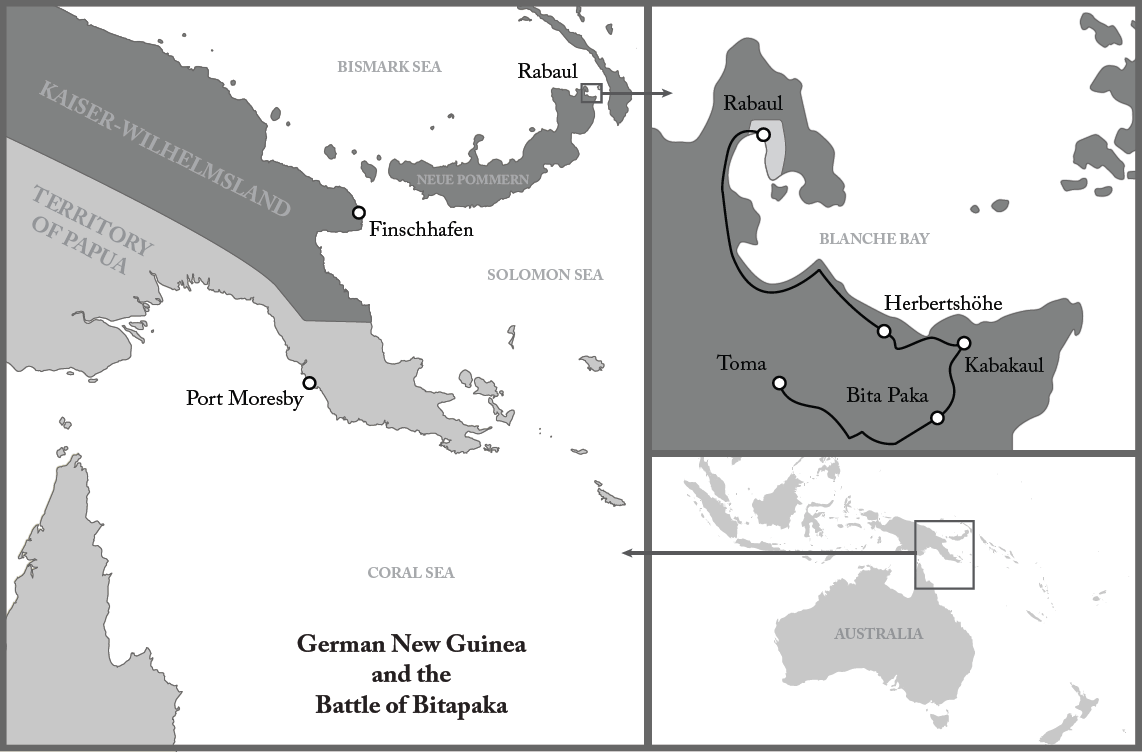

Soon enough, another theme emerged. There is a modern view that the First World War was a quarrel between the crowned heads of Europe and their arms makers, and, therefore, that distant Australia had no reason to enter the fight. There is enough truth to the first part of that argument to provide a flimsy platform for the second. But it ignores the facts. In 1914, the Kaisers Germany had a flourishing colonial empire in China, East Asia and the Pacific Ocean. German New Guinea, Deutsch-Neuguinea, stood at our very doorstep. The Kaisers navy had laid detailed plans to attack our seaborne trade, to sever the links of commerce and communication between Britain and Australia (and New Zealand as well) and to send powerful warships to bombard Sydney and Melbourne and other port cities. Our country was directly menaced by Imperial Germany, lying just over the horizon a threat that our forebears, save for a few pacifists, very well understood and took precautions to meet and counter. It was a time when Australians, of overwhelmingly Anglo-Celtic origin, thought of themselves as far-flung standard-bearers for a British race and Empire. To stand aside from the scrap was unthinkable, impossible. But offering support was not enough. Men of foresight had campaigned for the newly federated nation to have its own navy, the first for any of the Kings dominions. They succeeded in building that navy against great odds, and, in doing so, they saved their country. The first Australian victories in the war to end all wars were won by sailors.

So it seemed that the book was worth expanding beyond the SydneyEmden fight, to examine the spirit of the times, the things that were done or not done to prepare us for war, and to write about how we, the people, carried ourselves when the great guns began firing.

It does not pretend to be a complete history. But I hope it is an absorbing tale.

NOTES ON THE TEXT

Many place names have changed since the end of the war in 1918. For example, Madras in India is now Chennai; the Chinese port of Tsingtao is Qingdao; the Netherlands East Indies have become modern Indonesia; and the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires are extinct. But, for the sake of clarity and consistency, I have used the names that were familiar at the time, with an explanation or annotation where it might help.

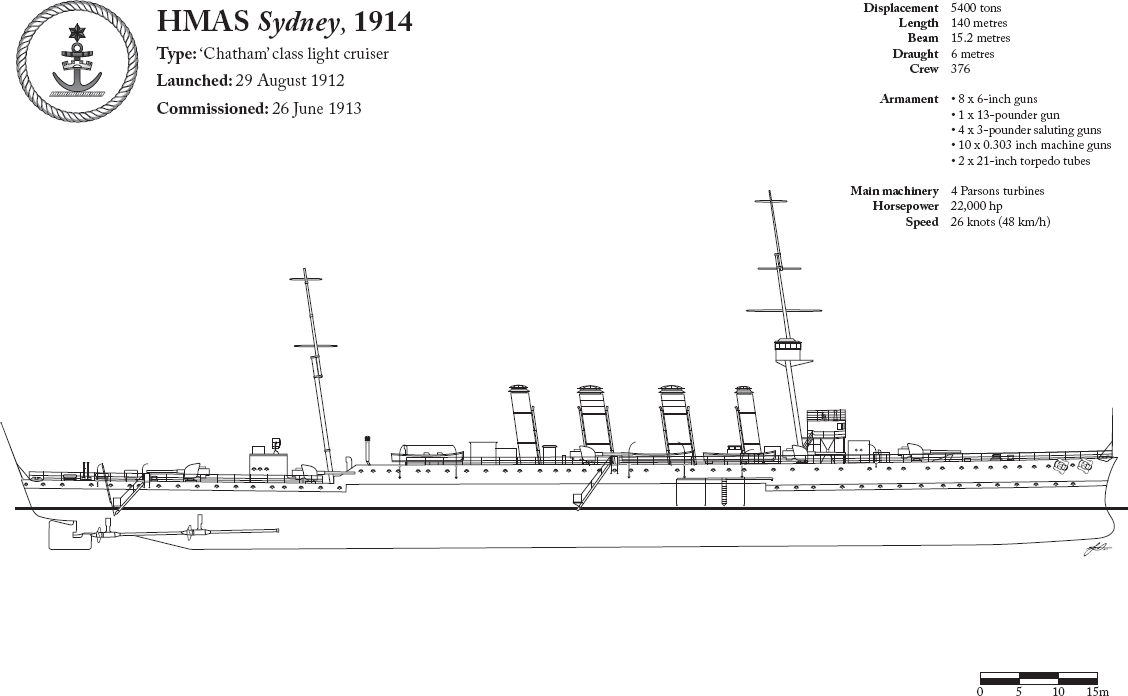

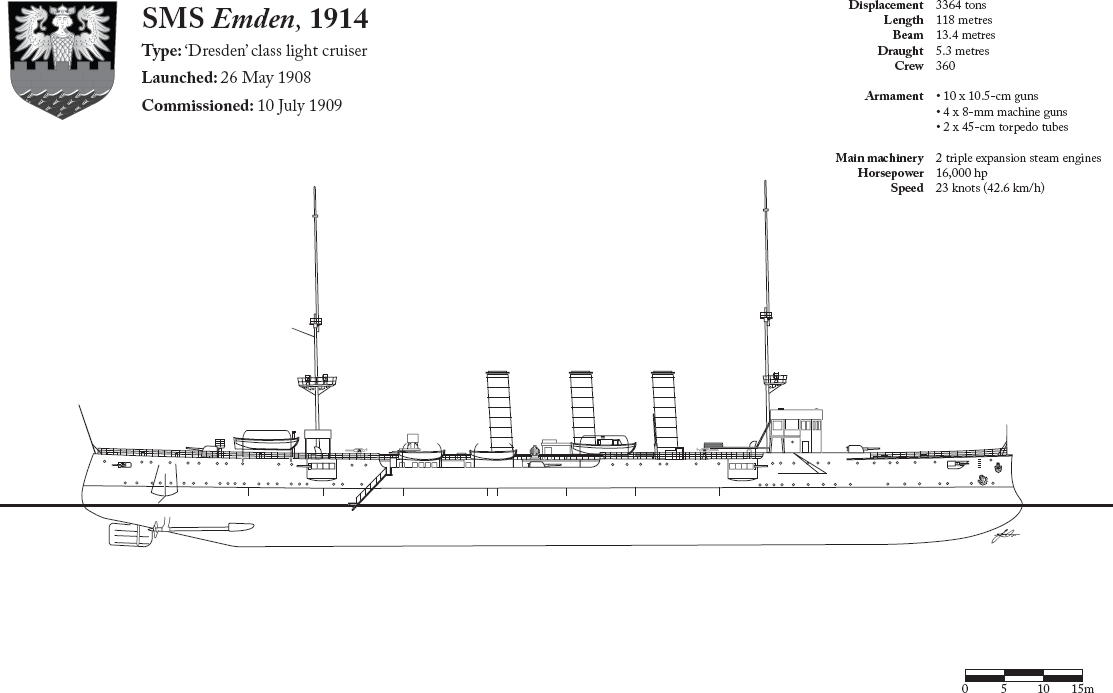

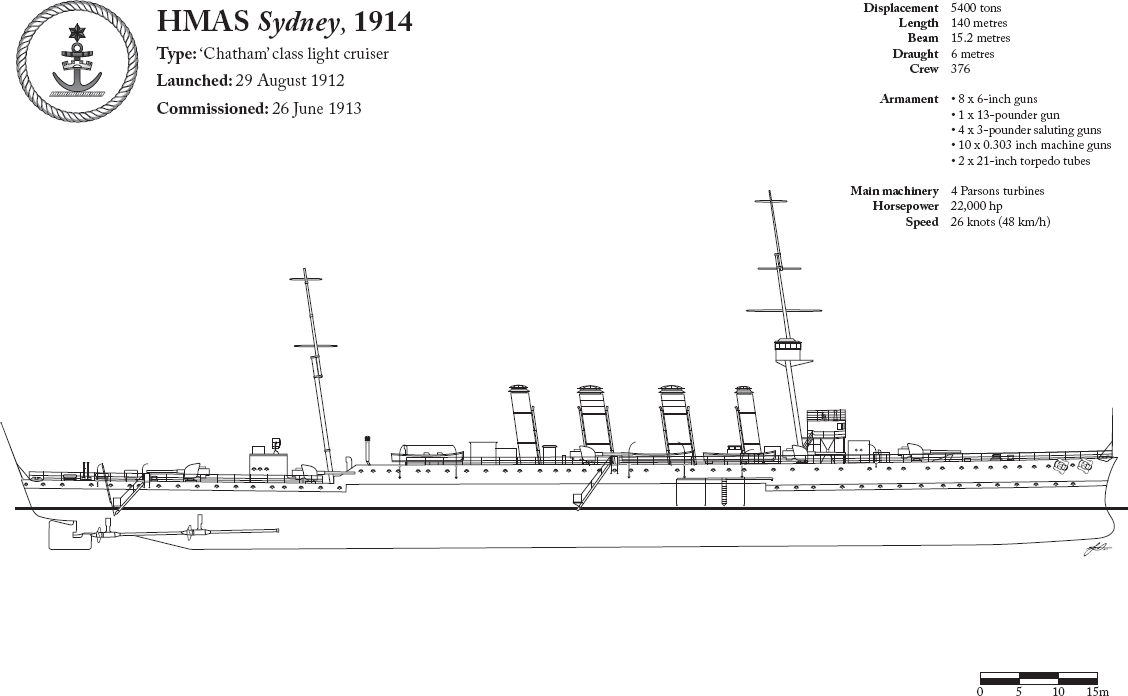

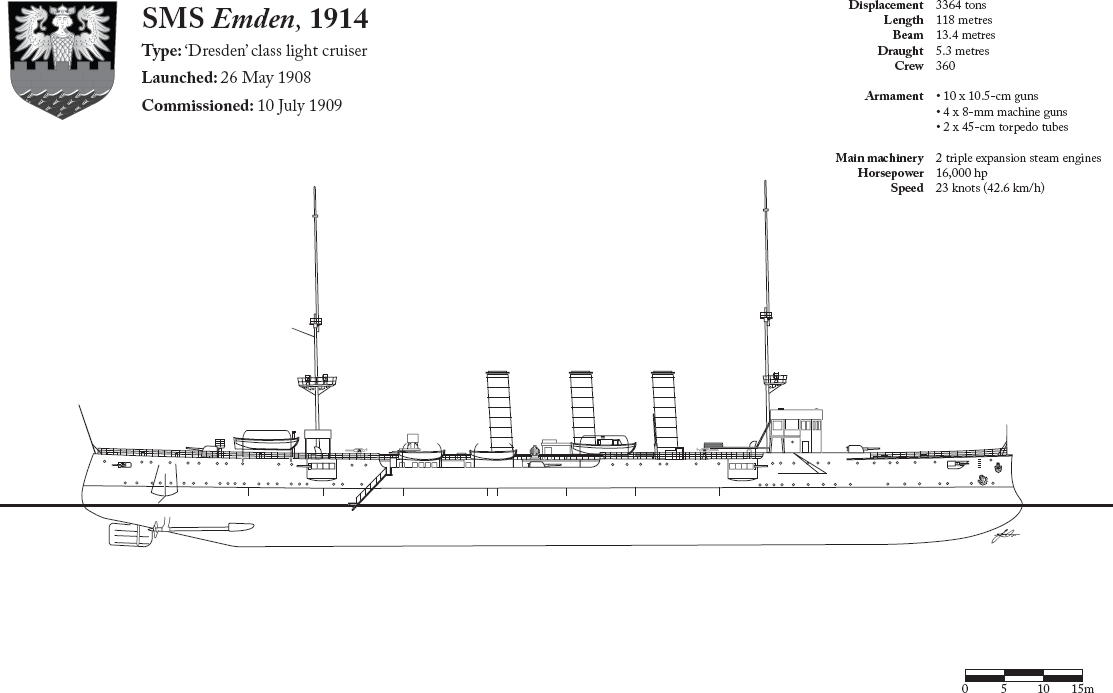

Most measurements have been converted to metrics. One hundred nautical miles is 185.2 kilometres. But I have kept speed at sea in knots, the way it is still measured. One knot is one nautical mile per hour. Do the sums, and 20 knots is just over 37 kilometres per hour.

Another exception is the size of guns, which I have also kept in their original units. The British and Australian navies measured the calibre of their guns in inches. A 6-inch gun fired a shell that was six inches in diameter. The Germans counted theirs in centimetres. Emdens heavy guns had a calibre of 10.5 centimetres, or just over four inches.

The value of money was another difficult area, saved by a helpful calculator on the website of the Reserve Bank of Australia. A basket of goods or services costing AU10 in 1914 would cost around $AU1050 today.