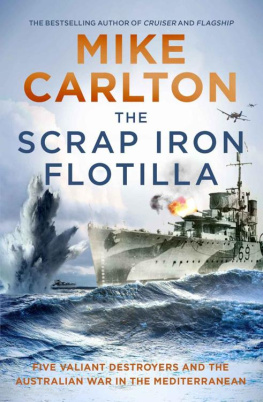

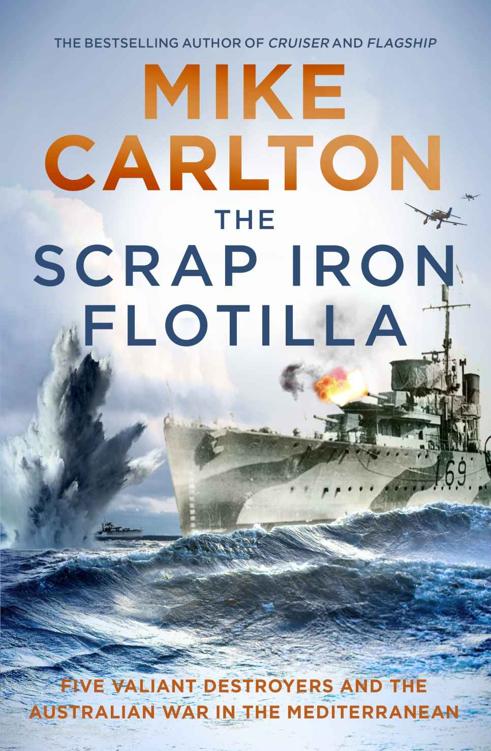

About the Book

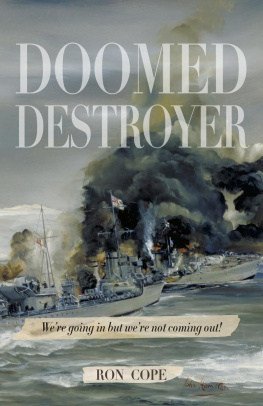

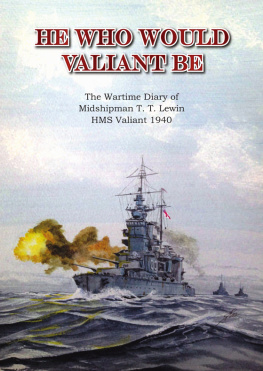

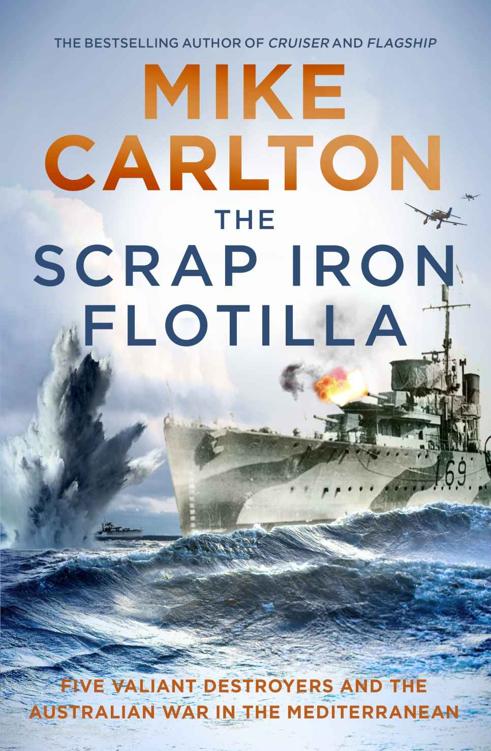

When the Second World War broke out in September 1939, Britain asked for help. With some misgivings, the Australian government sent five destroyers to beef up the British Royal Navy in the Mediterranean.

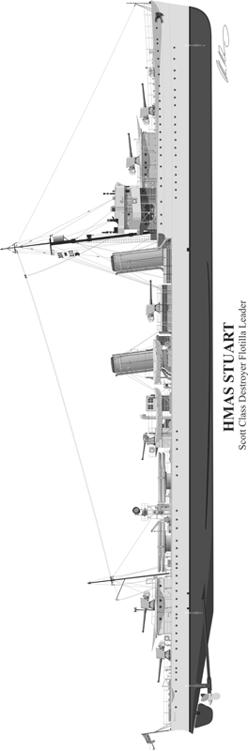

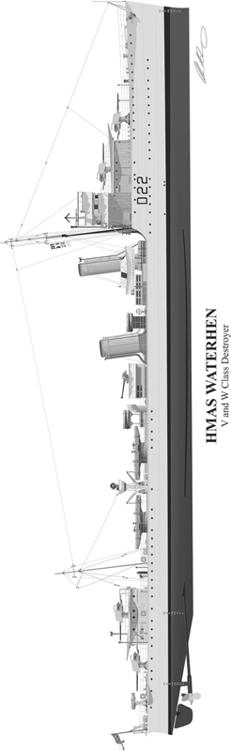

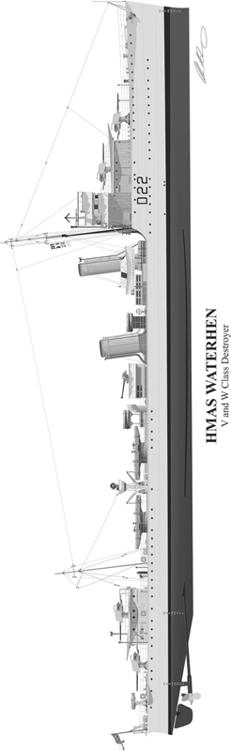

HMAS Vendetta , Vampire , Voyager , Stuart and Waterhen were old ships, small with worn-out engines held together by string and chewing gum, their crews liked to joke. The Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels sneered that they were a load of scrap iron.

Yet by the middle of 1940 they were valiantly escorting troop and supply convoys, hunting submarines and bombarding enemy coasts. Sometimes the weather was their worst enemy from filthy sandstorms blowing off North Africa to icy gales from Europe that whipped up vast seas and froze the guns. Life on board was hard: a bucket of water to wash; crowded, stinking sleeping quarters; monotonous meals of spam and tinned sausages. And always the bombing, the bombing. And the fear of submarines.

When Nazi Germany invaded Greece, the Allied armies including Australian divisions reeled in retreat. The Australian destroyers joined the rescue of thousands of soldiers. Then came the Siege of Tobruk Australian troops holding out in that small Libyan port. The destroyers ran the hazardous Tobruk Ferry bringing supplies of food, medicine and ammunition into the shattered port by night, and taking off wounded soldiers.

In late 1941 the ships were finally sent home. They adopted the Nazi insult as a badge of honour, and the Scrap Iron Flotilla is now an immortal part of Australian naval legend. This is its story.

CONTENTS

NOTES ON THE TEXT

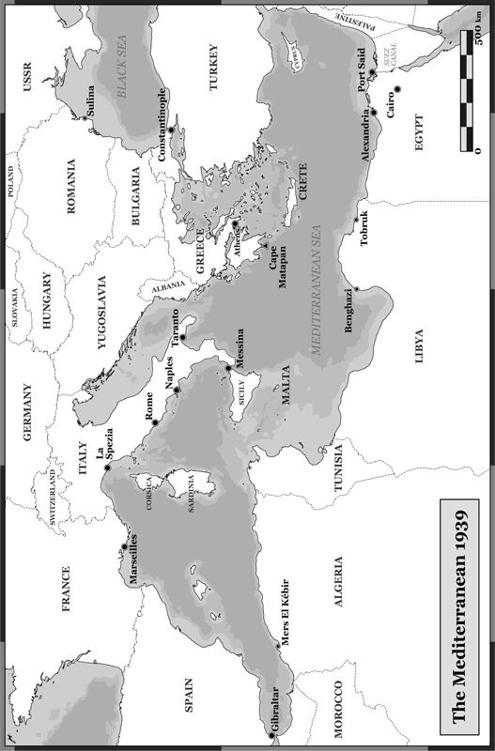

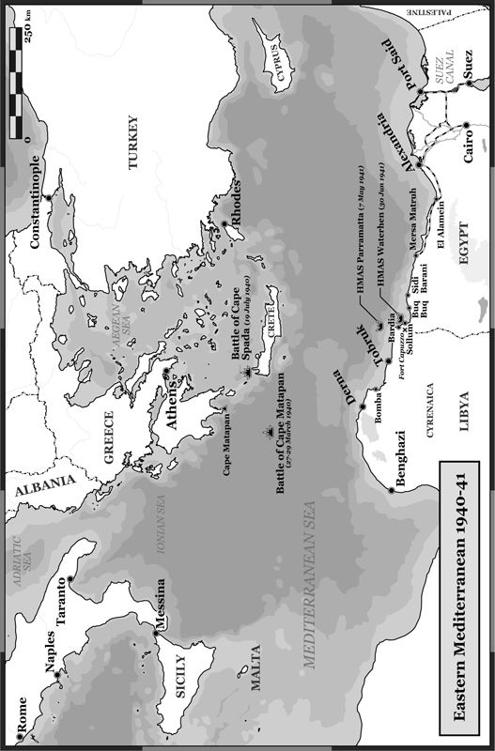

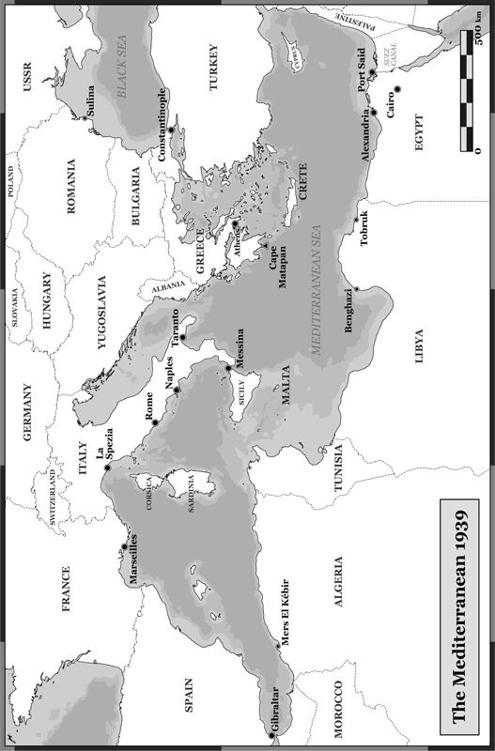

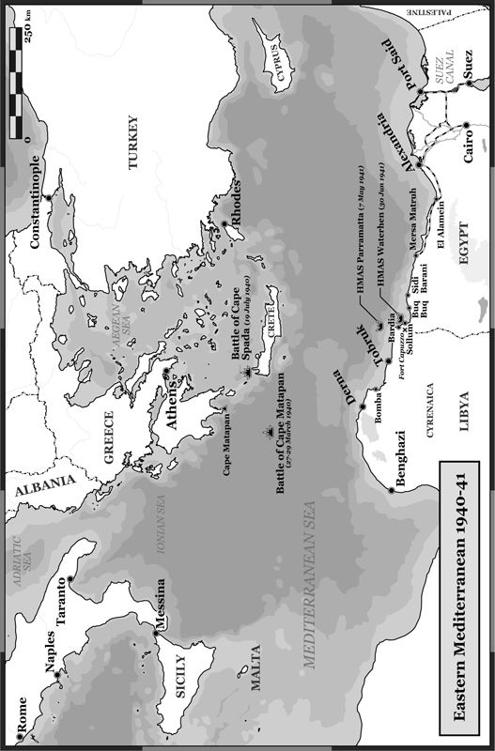

The map of the Mediterranean has changed radically since 1945. New countries have emerged Lebanon and Israel to name just two and many cities and ports now have different spellings or, in some cases, new names entirely.

For example, Sollum, on the Egyptian coast, is now Sallum or El Salloum, while Bardia, in modern-day Libya, is now Bardiyah. To keep it simple, I have mostly stuck with names, places and spellings as they were known during the Second World War. Then again, for clarity, I have sometimes done the reverse: Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were well enough known in 1940. Libya works better today.

Measurements of length and distance have been converted to metres and kilometres, except where they occur in direct quotations. Where it does crop up, a nautical mile is 1.8 kilometres. A knot is a measure of speed at sea, one nautical mile per hour. Thus a ship travelling at 30 knots is doing 30 nautical miles per hour or 55.5 kilometres per hour (km/h). This might not seem much to a car driver on land, but at sea especially in a big sea it is tearing along at a great pace.

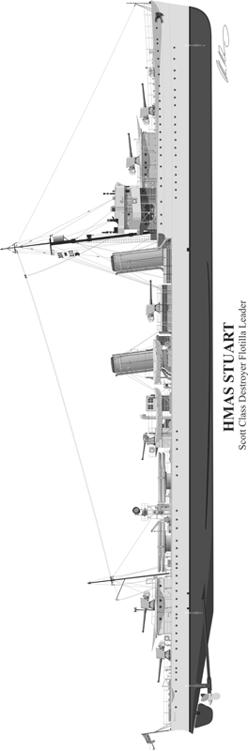

Gun calibres are also tricky. In the Allied navies they were measured in inches; in the Italian and German navies in centimetres. I have retained inches. HMAS Stuart s main armament of 4.7-inch calibre guns fired a shell of that diameter, or 11.9 centimetres. A 6-inch cruiser had main guns of that calibre, or 15.2 centimetres. The bigger the shell the more explosive it carried and the further it went.

Port is the left-hand side of a ship as you look forwards towards the bow. Starboard is the right-hand side. They remain the same, though, even if you turn to face the rear. Focsle, an abbreviation of the old forecastle, is the front section of a ship, including the upper deck there and decks immediately below. The quarterdeck is on a ships stern, the rearmost part. The head is a toilet, a name from the days of sail when seamen used the head of the bow (the front of the ship) as a latrine.

To be captain of a ship is a job description or an appointment, not a rank. Some ships captains might be commanders, lieutenant commanders or even lieutenants. The crew would refer to them as the captain even though they might not hold that captains rank of four gold stripes. Today, the second in command of a ship is usually known as the executive officer, or XO. In the destroyers of the Second World War he was the First Lieutenant. A flag officer is one who holds the rank of rear admiral or above. A kapitnleutnant in the German Kriegsmarine held the equivalent rank to a British or Australian lieutenant.

Not all warships are battleships, which is a specific term. A battleship was a large, heavily armoured warship carrying a navys biggest and most powerful guns. It had no means of detecting or fighting submarines, having to rely on a surrounding screen of destroyers and cruisers for that protection. Battleships were designed to fight other battleships or to bombard targets ashore. A battlecruiser was similar, about the same size as a battleship and also with big guns, but carrying less protective armour and designed for more speed. Neither of these exists today outside maritime museums, their place taken by aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines carrying ballistic missiles.

Finally, this is not a history of every Australian ship that served in the Mediterranean in the early years of the Second World War. That book would have to be twice as long as this one. I have focused on the five old destroyers of the Scrap Iron Flotilla Stuart , Vampire , Vendetta , Voyager and Waterhen because their stories are unique and magnificent, as I hope will become apparent. At the same time, a couple of other ships found their way in. The cruisers HMAS Sydney and Perth and the sloop Parramatta have an honoured place as well.

CHAPTER 1

THE THEATRE

Yea, and if some god shall wreck me in the wine-dark deep,Even so I will endure...For already have I suffered full much,And much have I toiled in perils of waves and war.Let this be added to the tale of those.Homer, The Odyssey

War at sea began in the Mediterranean, the centre of the earth. In myth and legend, Greek and Roman gods and heroes rowed and sailed its waters to fight their battles. Odysseus and Achilles, Ajax and Hermes, Aphrodite and Artemis, Jason and his Argonauts all furrowed its waves or strode its shores. Zeus, the God of War, and Poseidon, the wrathful God of the Sea, held the fate of men and women in their hands. Paris, son of Zeus, abducted the beautiful Helen of Troy, the face that launched a thousand ships of the Trojan Wars.

Down the centuries before and after Christ, great cities and nation states, republics and kingdoms and caliphates and empires rose and fell on the Mediterranean littoral of Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Minoans and Greeks, Romans and Carthaginians, Persians and Byzantines, Phoenicians and Ottomans, Genoese and Venetians hurled their fleets at each other in sea fights evermore violent as their ships and weapons and tactics grew more capable of slaughter. Triremes and galleys rowed by banks of slaves gave way to sailing galleons. The armoured ram on the prow of a warship was superseded by the catapult hurling mighty rocks at the enemy, to be supplanted in turn by gunpowder and cannon firing iron balls.

Next page