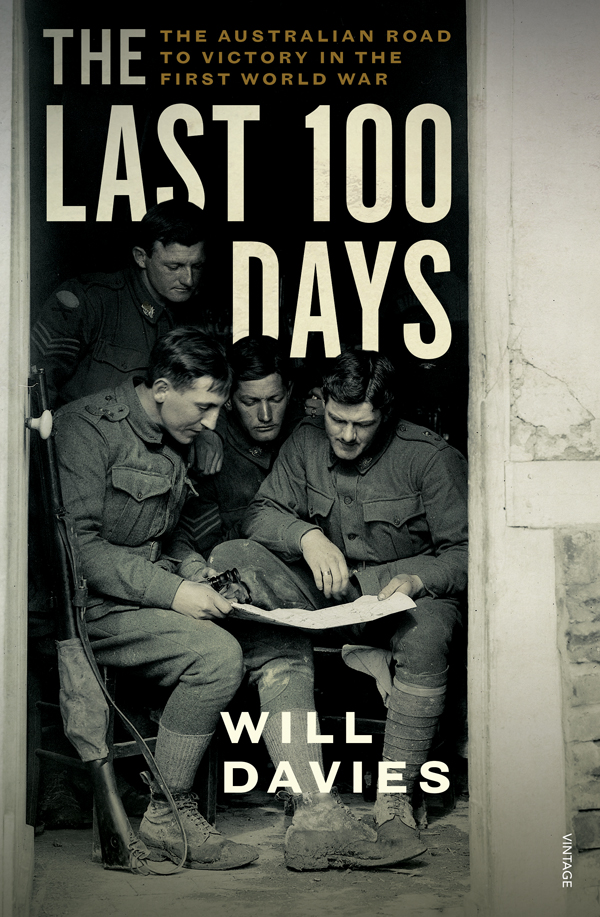

About the Book

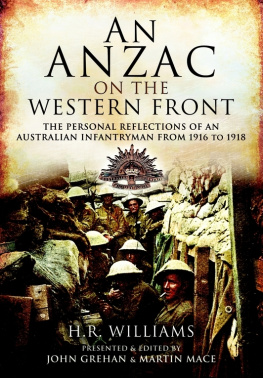

Much has been written about the Great War, and a great deal on the Australian Imperial Force and its operations. Now Will Davies, bestselling author of Beneath Hill 60 and Somme Mud , is the first to explore, in vivid detail, the last 100 days and the Australian contribution to final victory in November 1918.

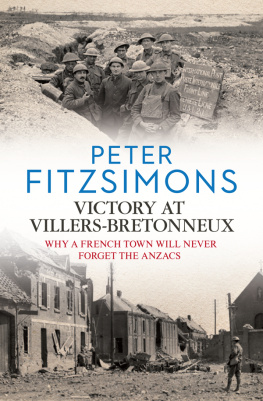

In March 1918, with the fear of a one-million-man American army landing in France, the Germans attacked. In response, Australian soldiers were involved in a number of engagements, culminating in the Second Battle of Villers-Bretonneux and the saving of Amiens, and Paris, from German occupation.

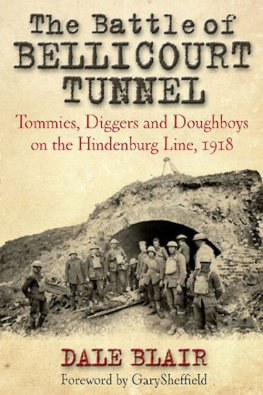

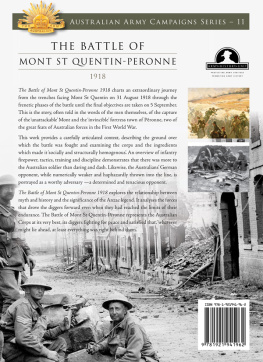

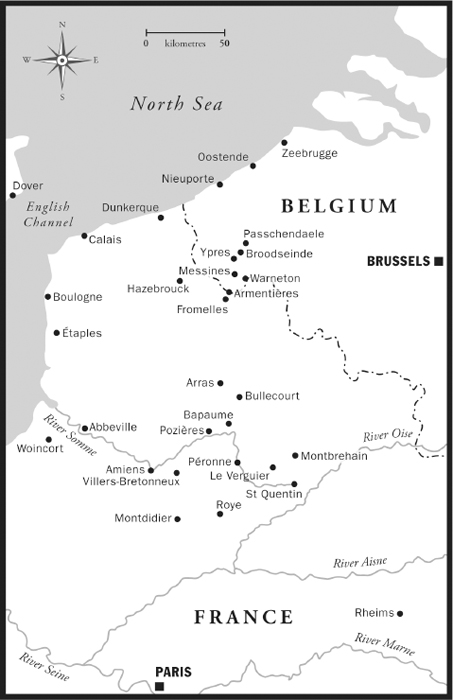

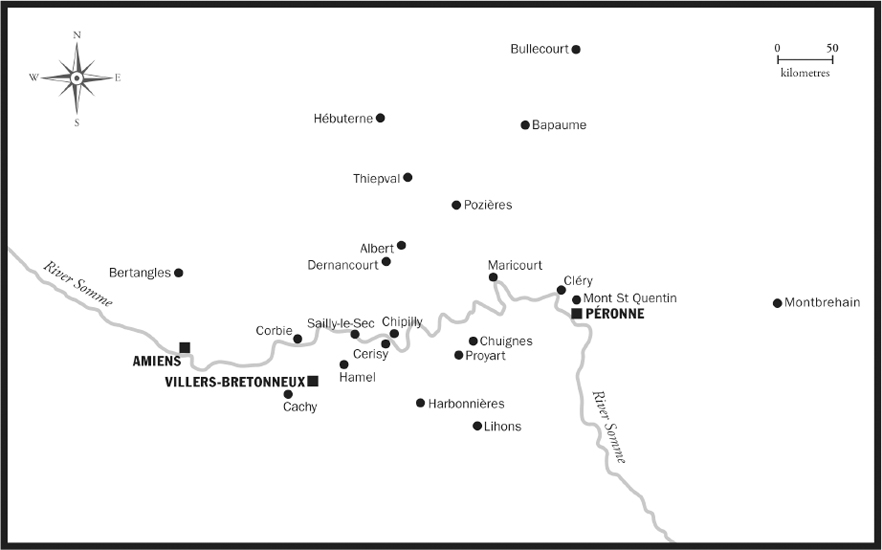

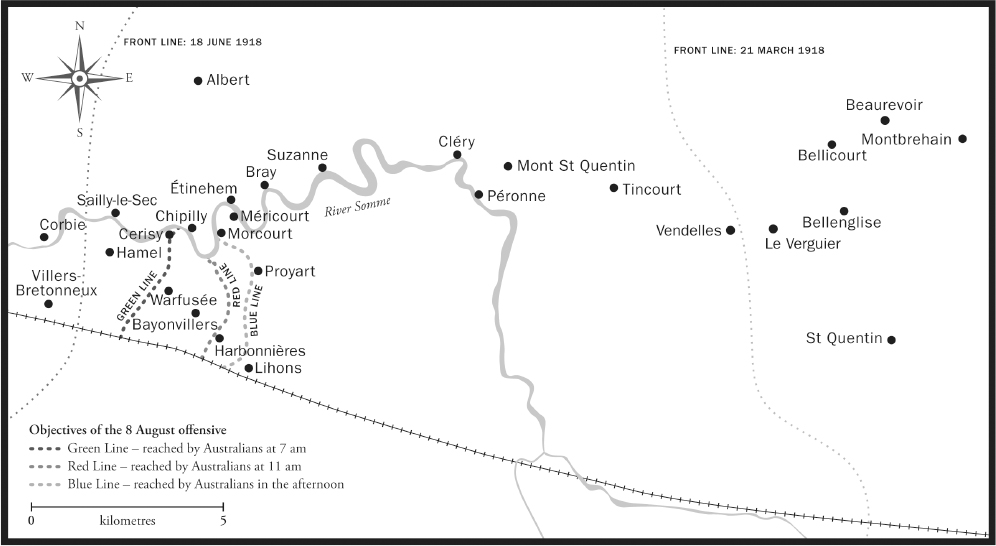

Then came General John Monashs first victory as the Commanding Officer of the newly formed Australian Corps at Hamel. This victory, and the tactics it tested, became crucial to the Allied victory after 8 August, the black day of the German Army. On this day the major Allied counteroffensive began, with the AIF in the vanguard of the attack. The Australians, with the Canadians to the south and the British across the Somme to the north, drove the Germans back, first along the line of the Somme and then across the river to Mont St Quentin, Pronne and on to the formidable Hindenburg Line, before the last Australian infantry action at Montbrehain in early October.

Fast-paced and tense, the story of The Last 100 Days is animated by the voices of Australian soldiers as they endured the wars closing stages with humour and stoicism; and as they fought a series of battles in which they played a pivotal role in securing Allied victory.

Will Davies is more than a historian: he has the rare gift of being a story weaver. His bestseller Somme Mud remains etched in my memory, and I can assure you The Last 100 Days is no less moving MAJOR GENERAL GORDON MAITLAND, AO, OBE, RFD, ED (RETD)

To Major General Gordon Maitland, AO, OBE, RFD, ED (Retd), and Mrs Dorothy Maitland.

Wonderful Australians.

Introduction

In 1994, with an inquisitive mind and a heavy heart, I wandered the battlefields of the Great War, particularly the Australian operational areas along the Somme, and the Ypres Salient to the north, for the first time. I had been motivated to go after I had felt deeply affected by the interment of the body of an unknown Australian, taken from Adelaide Cemetery at Villers-Bretonneux and placed in the Hall of Memory at the Australian War Memorial, in November of the previous year.

Since that first trip in 1994, I have continued to go back to the battlefields of the Western Front to better understand Australias sacrifice and contribution to the war effort. After 2004 I returned regularly to walk the battlefields and research a series of books on the Great War, starting with the edit of the now classic story Somme Mud .

The battlefields still draw me back. Even now, 100 years on from the destruction and death of the Great War, the battlefields of France and Belgium continue to reveal so much about the men who fought and died there. While the tortured earth, the vast fields of mud and shell holes, upturned wagons and remnants of dead horses and men have long gone, the landscape still tells a vivid story.

A few years ago the Australian publics attention turned from the Gallipoli campaign to the Western Front. The Great War centenary celebrations, starting with Fromelles and Pozires in 2016, increased this public interest in the areas history and saw a rise in the number of visitors to the Australian operational areas of the Western Front.

Yet there remains little understanding of the very last battles, indeed the last 100 days, that saw the Australian Imperial Force at its fighting best Australians at last controlling and planning their own battles and their own destiny with an Australian, General John Monash, in command. In the lead-up to victory, the men of the AIF were more enthusiastic, energised and confident than they had been for years. The AIF, they knew, was a formidable fighting machine, feared by the enemy, respected by the British High Command, and celebrated by the people of their new nation.

Recently I visited the areas from Corbie to Montbrehain, tracing the Australians advance in those last 100 days: first with the attack in early July at Hamel, up the Somme valley, across the river to Mont St Quentin and Pronne, and then east following the advance towards the Hindenburg Outpost Line and finally the Hindenburg Line itself. This is an area rarely visited by Australians, particularly the area around the lonely 4th Division Memorial above the St Quentin Canal near Bellicourt. While I had previously been east of Pronne, this was the first time I had studied the area and the Australian actions in any detail.

In the same way these important battlefields, stretching from Villers-Bretonneux to Montbrehain, had lacked visitors, it seemed very little had been written about them, or about the last 100 days of the war.

These battles of 1918 raged across beautiful country, particularly the Somme villages, and then out into the rolling green hills to the east. Even in August and September 1918 this area was not the shattered, desolate mud-fields of the Somme, but working farmland with fields of wheat, rapeseed and sugar beet, the terrain free of fence lines.

It is from these battlefield wanderings, and due to the absence of popular writing on this period of history, that my desire to tell this story began. I have always believed that to understand history, truly understand it, you must visit the areas where it took place. Though this wont always be possible, I hope this book will help to bring those places to life to tell the soldiers stories.

In writing this history, I have relied on two main sources: the daily war diary entries from the fifteen AIF brigades and sixty battalions; and the battalion histories written after the war, including more recent work, particularly of the prolific researcher and writer Neville Browning. In this regard, I hope to capture the voice of the time. I have aimed to tell these soldiers stories not as a simple rewriting of details and events, but as an echo from the time; of these soldiers matter-of-fact recounts of life on the ground, of their attitude to the enemy, and their varied responses to death and loss even as they marched to victory.

Will Davies

February 2018

At the beginning of 1918, the war had been fought for nearly three and a half years. By this point, few of the men who had left Australia for Gallipoli in late 1914 were still alive and, if so, were unwounded and sound of mind. The Australian Imperial Forces introduction to the Western Front was at the butchers picnics at Fromelles and Pozires in 1916. Within the first two months on the Western Front, the AIF had seen nearly fifty per cent of its ranks decimated. Then the frightful battles of Bullecourt, Messines and Passchendaele in 1917 had dramatically thinned their ranks even further, leaving the AIF desperately short of men. In 1917 alone, the AIF sustained nearly 77,000 casualties, twice the casualties of the 1916 battles and three times the casualties of the Gallipoli campaign. To compound these losses, recruitment numbers were low in Australia, and two referenda had failed to indicate the publics support for conscription. Further, unlike their British allies or their German enemy, the men could not return home, see their family and loved ones, or breathe in the gum-scented air or the salty sea breeze. Australia was a distant memory. The Australians were exhausted, and death seemed inevitable.