Campaign 49

Mons 1914

The BEFs tactical triumph

David Lomas Illustrated by Ed Dovey

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

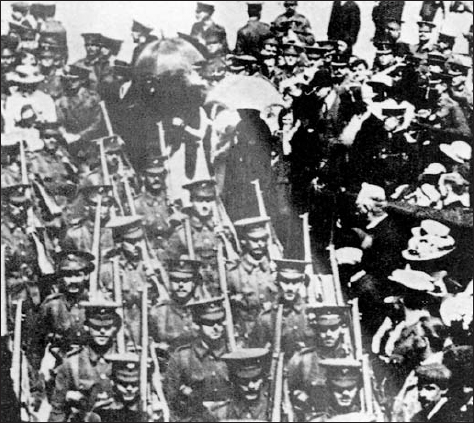

British troops, probably of the 8th Brigade, II Corps, resting on their way to Mons. Note the cobbled paved road surface which caused a good deal of discomfort to many soldiers. (Mons Museum)

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

W ere off to fight the bloody Belgians! an enthusiastic British soldier informed an astonished listener in the first, exciting days of August 1914. The European war, so long predicted, so long feared, had come at last, sparked by a handful of shots fired by a consumptive Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo.

The Entente Cordiale between Britain and France was little more than an understanding of mutual support should war come. The British had, though, given an assurance that the Royal Navy would not allow a foreign fleet into the English Channel and there was a further unspoken assumption that a British Expeditionary Force would help repel an invader from French soil.

Henry Wilson, who became Director of Military Operations in 1910, was an obsessive Francophile. Entirely on his own initiative, he promised the French that a British Expeditionary Force of six infantry divisions and one cavalry division would be sent to France. Under Wilsons guidance, mobilisation plans were produced with a single aim to get the BEF cross the Channel quickly enough to join a French offensive planned to start 15 days after mobilisation. The French courteously dubbed Wilsons scheme Plan W.

12 August 1914 The 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards march out from Chelsea Barracks. (Private Collection)

On the afternoon of 5 August 1914, Herbert Asquith, the British Prime Minister, presided over a hastily arranged Council of War and discovered that Plan W was the only one available and capable of implementation. One change was made: two divisions the 4th and the 6th were kept back against the threat of a German invasion of Britain.

A British Expeditionary Force of four infantry divisions and one cavalry division supported by an extra cavalry brigade would go to war. It would be commanded by Sir John French; the four infantry divisions would form I Corps, commanded by Sir Douglas Haig, and II Corps would be under Sir James Grierson. Major-General Allenby had command of the Cavalry Division.

German Guard Infantry in Berlin entraining for the front, August 1914. (Private Collection)

A few days later, Sir John French received his instructions from Lord Kitchener, the War Minister, and one of the few men who anticipated a long struggle. Kitchener had little faith in Sir John Frenchs abilities and distrusted Henry Wilson. His words reflected this concern. Sir John French was to support and co-operate with the French Army... in preventing or repelling the invasion by Germany of French and Belgian territory and eventually to restore the neutrality of Belgium. The instructions continued: It must be recognised from the outset that the numerical strength of the British Force... is strictly limited... the greatest care must be exercised towards a minimum of losses and wastage. Therefore, while every effort must be made to coincide most sympathetically with the plans and wishes of our Ally, the gravest consideration will devolve upon you as to participation in forward movements where large bodies of French troops are not engaged and where your Force may be unduly exposed to attack. In this connection I wish you distinctly to understand that your command is an entirely independent one, and that you will in no case come in any sense under the orders of any Allied General.

They were phrases to make anyone pause. The BEF was to help throw back one million Germans and restore Belgian independence, but to avoid heavy losses while doing so. It was to be part of French plans, yet remain independent despite the fact that it was only one-thirtieth the size of the French army, and was operating on French soil and relying on French goodwill for railways and rolling stock, accommodation, communication and supply lines, and myriad other requirements. It was hardly a promising start.

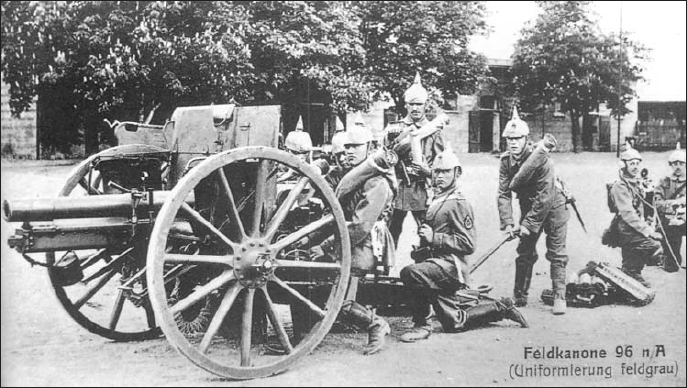

The German Model 96 field gun, seen here with a crew from the 4th Bavarian Royal Field Artillery Regiment, created severe problems for the BEF in the first months of the war. It was an ominous portent for what proved to be a war in which artillery caused the greatest casualties. (Authors Collection)

THE OPPOSING COMMANDERS

THE BRITISH COMMANDERS

F ield Marshal Sir John French was 62 years old in August 1914 and had an outstanding record of distinguished service, being one of the few senior officers who enhanced his reputation during the South African War.

Field Marshal Sir John French had resigned from his position as Chief of the Imperial General Staff in 1914 in protest over the Governments Irish Home Rule Bill. When war was declared, he was offered command of the BEF. Quick-tempered to the point of explosive, French was personally brave and much liked by his men. (Authors Collection)

French was a cavalryman, and not at heart a staff officer but a fighting soldier, a quality which endeared him to his troops and gained both their respect and affection. He went to France full of confidence, convinced that he could lead the BEF to a part in a swift and decisive victory. French had a hot temper and was quick to take offence; he harboured grudges. Worse, for a commander, he suffered from mercurial changes of mood, plunging from enormous optimism to deep pessimism in a matter of moments.

General Sir Douglas Haig, commanding I Corps, was another highly regarded officer. As a pre-war Director of Military Training, Haig was not only the architect of Field Service Regulations which essentially prepared the British Army for a European war, but he had also been responsible for the organisation and training of the Territorial Army. Naturally shy, Haig was not a fluent speaker and was often tongue-tied in debate, a drawback which was to cause him many problems. He was, nonetheless, a very capable soldier who believed firmly in total attention to detail, and close and constant co-operation between all arms. Haig had the respect and admiration of his officers and earned intense loyalty from those who served closely with him. He was one of the few who believed that a European war would be a long and difficult struggle.