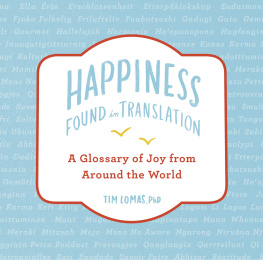

Lomas - Translating happiness: a cross-cultural lexicon of well-being

Here you can read online Lomas - Translating happiness: a cross-cultural lexicon of well-being full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London;Cambridge;Mass, year: 2018, publisher: MIT Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Translating happiness: a cross-cultural lexicon of well-being: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Translating happiness: a cross-cultural lexicon of well-being" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Translating happiness: a cross-cultural lexicon of well-being — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Translating happiness: a cross-cultural lexicon of well-being" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Tim Lomas

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2018 Tim Lomas

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in ITC Stone Sans Std and ITC Stone Serif Std by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lomas, Tim, 1979 author.

Title: Translating happiness : a cross-cultural lexicon of well-being / Tim Lomas.

Description: Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017029082 | ISBN 9780262037488 (hardcover : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780262344623

Subjects: LCSH: Language and emotions. | Well-beingPsychological aspects. | Interpersonal relations. | Happiness. | Psycholinguistics.

Classification: LCC BF582 .L66 2018 | DDC 158dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017029082

ePub Version 1.0

I can remember vividly the moment when I first had the notion to create a positive cross-cultural lexicography, the project on which this book is based. It was a summer day in 2015, and I was standing in my parents kitchen in London, chatting with my mum. In retrospect, though, its seeds were planted years before, way back in 1998.

I was nineteen and had gone to teach English in China for six months before starting university. The adventure was every bit as eye-opening and horizon-expanding as you might expect for a nave, unworldly young man like me. It was challenging at every turn, testing my skills and character to the limit. But at the same time, it was thrilling and intoxicating. My world was enriched daily as I encountered new and unfamiliar people, practices, experiences, sights, sounds, tastes, and, above all, ideas. I was especially intrigued by the Taoist and Buddhist monasteries, and I sought out books and people who might explain these traditions, unknown and mysterious to me.

I soon became bewitched by terms such as Tao and yn-yng, nirva, and sasra. The meanings of these concepts were opaque at best, in fact mostly unfathomable. But they seemed deeply significant. I was struck, unnerved even, by the realization that these words lacked an exact English equivalent. But they were not just untranslatable. They seemed beyond my linguistic and cognitive universe. I was radically challenged. I became aware, really for the first time, that some concepts and practices which belong to cultures not my own are veiled to me.

This realization stayed with me as I entered university in Edinburgh to study psychology. I found the field fascinating, and during my studies was introduced to a wealth of interesting ideas and theories. But I still felt that the concepts I had encountered in China remained outside my frame of reference, indeed beyond the ken of Western psychology. One would be unlikely to find even a passing reference to nirva in a textbook, let alone a serious analysis of it.

Why, I wondered? In numerous cultures, the state of nirva is considered the peak of human development. It couldnt be unimportant to psychology. However, academic psychology, as I was learning it, seemed at best incomplete. It is rootedunderstandably, given the context in which it emerged and developedin philosophies and epistemologies that are and have been dominant in Western cultures. This is fine, as far as it goes. But it does mean that psychology has largely overlooked the deep insights into the mind that other cultures have cultivated over the centuries.

(Following Edward Saids warnings about Orientalismhis critical term for the construction of the East in a way that homogenizes and moreover disparages Asians, Middle Easterners, and North Africans as OtherI hesitate to use the terms Eastern and Western, and moreover to ascribe particular concepts and attributes to these two hemispheres. That said, these labels have a ring of truth for me, capturing my initial unfamiliarity with ideas I experienced as culturally otherin an essentially positive way, I hasten to add.)

My impressions of psychologys cultural bias lingered. After some years working as a musician and a psychiatric nursing assistant, in 2008 I obtained a PhD scholarship to study the impact of meditation on mens mental health. It was a dream project, since after my return from China I had personally developed a meditation practice and a keen interest in Buddhism. Moreover, the PhD brought me into further contact with concepts and practices that were culturally unfamiliar to me but seemed relevant to psychology.

My study centered on a group of meditators in London. In a spirit of ethnography, I joined their Buddhist community. I found myself dwelling further on terms that could be regarded as untranslatable, and on the phenomena they signify. For instance, my study participants attested to the importance of the sagha, a Pli word for community, generally used within Buddhism to denote an established group of practitioners. Sagha provided the warmth of connection and friendship, but it was also a community of practice. Of particular fascination to me was that untranslatable terms such as mett were not merely intellectual curiosities. These men were engaged in a heartfelt effort to bring these concepts into the center of their lives, where they would be part of everyday discourse and influence their behavior.

The possibility of thoughtfully harnessing untranslatable words in this way would have a strong effect on my subsequent conception of the lexicography presented in this book. That project, however, would wait another few years. I wrapped up my PhD in 2012 and soon after gratefully took up a lectureship at the University of East London in the arena of positive psychology. I felt at home in this exciting and relatively new branch of academiadeveloped since the late 1990swhich can be regarded as the science and practice of improving well-being. I spent the next couple years immersing myself in the field, which proved a garden of delights. That brings me back to my parents kitchen.

I had just returned from the biennial International Positive Psychology Association conference, where I enjoyed a week of fascinating talks and inspiring conversations. Ideas were bubbling away in my mind. One presentation in particular made a mark on me. It was a talk by a Finnish researcher, Emilia Lahti, on the concept of sisu, which she described as a form of extraordinary inner courage and determination in the face of adversity. Sisu, she explained, was understood in Finland as a quality integral to its culture and people, enabling them not only to survive but also to thrive in the face of hardships encountered over their long history. But Lahti also suggested sisu was not only a strength manifested by, or available to, Finns. It was potentially within reach of all people, regardless of their background, even if their own language lacked a term to signify it.

When I got to my parents house, my mum asked about the conference. With much enthusiasm, I told her about sisuand its intriguing lack of a precise English equivalent, even as there are conceptually similar terms. The train of conversation led us to reflect that most languages may have similarly untranslatable words. I now know that there is a considerable academic literature on this topic. However, being a psychologist rather than a linguist, at the time I wasnt aware of the concept of untranslatability per se, notwithstanding my earlier experiences in China. As such, this conversation yielded something of an epiphany. My mum and I spent a while drumming up possible examples from among our own pool of languages: we both speak French, though my skill is sadly limited and fading fast; my mum is fluent in German, and has some knowledge of Arabic; and I have an abiding interest in Chinese, courtesy of my formative months there, as well as Sanskrit and Pli, thanks to my interest in Buddhism.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Translating happiness: a cross-cultural lexicon of well-being»

Look at similar books to Translating happiness: a cross-cultural lexicon of well-being. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Translating happiness: a cross-cultural lexicon of well-being and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.