Constable & Robinson Ltd

5556 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Constable

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2007

Translated from the French: Frres des Tranches, published by

Edition Perrin in 2005.

Copyright Marc Ferro, Malcolm Brown, Rmy Cazals,

Olaf Mueller, 2007

The right of Malcolm Brown, Rmy Cazals, Olaf Mueller and Marc Ferro to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act, 1988.

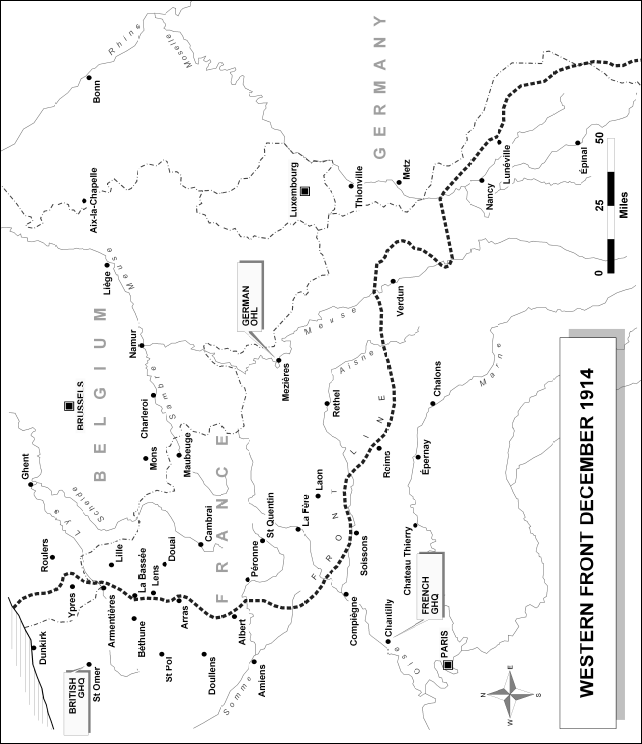

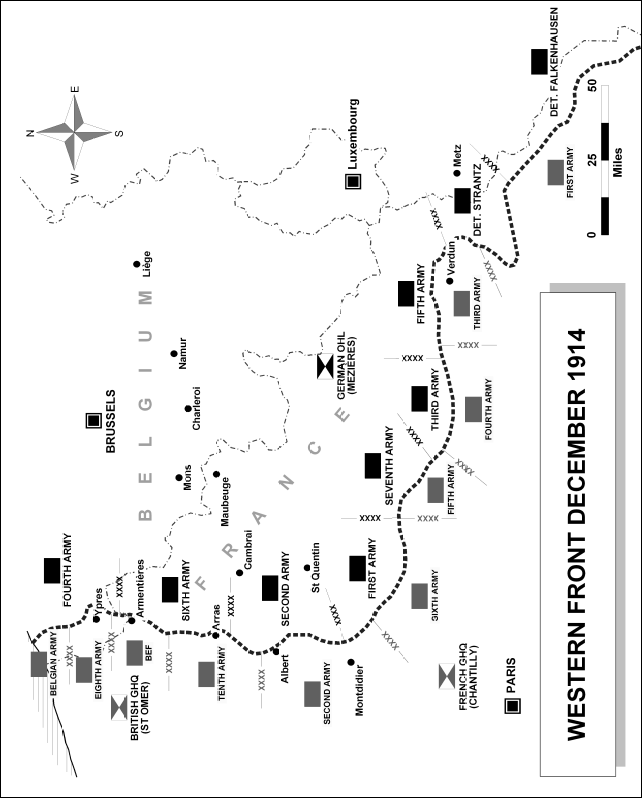

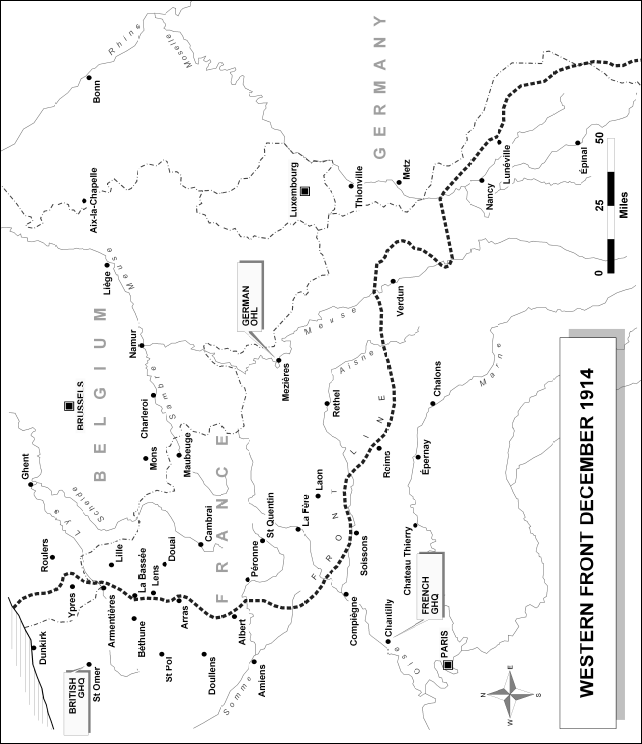

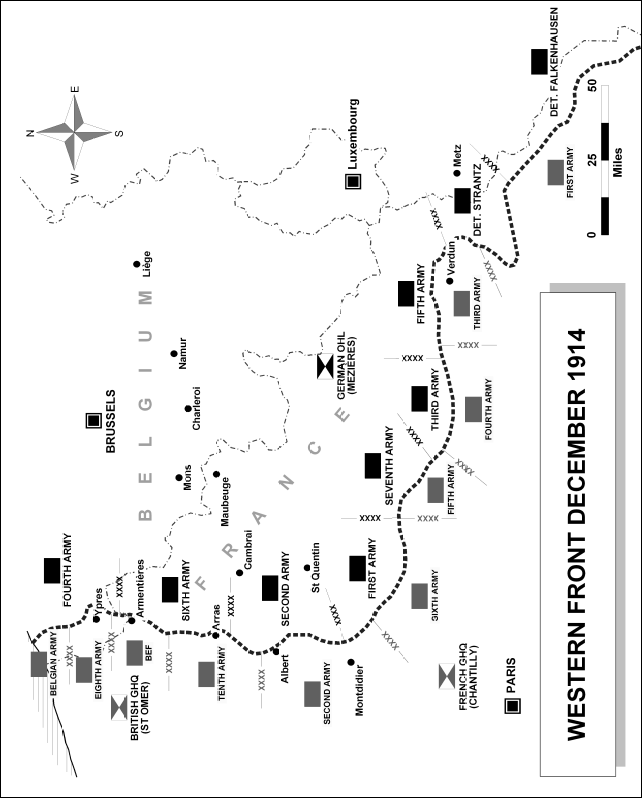

Maps by Christopher Summerville

Translations Helen McPhail, 2007

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is

available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84529-513-4

eISBN: 978-1-47211-280-4

Printed and bound in the EU

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Jacket image: Illustrated London News Picture Library; Design: Bob Eames

Contents

Introduction to French Edition:

The Realities of Fraternization in the First World War |

Translators Note

M ilitary hierarchy is important in the incidents and relationships narrated in these chapters and French military ranks are therefore translated into their British Army equivalents. French army units are shown under their normal number or abbreviation; the initials RI indicate Regiment dInfanterie, or Infantry Regiment, while BCP refers to a battalion of Chasseurs Pied, the equivalent of the British Armys Light Infantry. The Tirailleurs Sngalais were African troops from various French colonies, the Zouaves came from Algeria and the Chasseurs dAfrique were light cavalry units formed to serve in Africa. The Gnie were the French Armys Engineers.

Introduction

T hat there was a truce at Christmas on the Western Front in the first winter of the First World War has become increasingly accepted in Great Britain as a historical fact. The episode was given honourable mention in the ground-breaking BBC series The Great War shown in the mid-1960s. It was featured briefly but memorably in both the stage and the film versions of Oh! What a Lovely War. Subsequently whether through radio and television programmes, newspaper and magazine articles or longer works, the story has slipped across the divide between myth and reality, seizing the imagination of many people in the process. I myself have played a part in putting a shoulder to this wheel, through the BBC Television programme Peace in No Mans Land, first transmitted in 1981, which I wrote and directed, and which included the filmed testimony of three former participants, and the book Christmas Truce, first published in 1984, of which I was co-author with Shirley Seaton.

Over time, indeed, the subject has aroused such interest that when in December 2006 a four-page anonymous letter describing the truce was put up for sale in a leading London showroom, it was given substantial coverage in the media, provoked a fierce contest at the auction and was finally knocked down for the almost incredible sum of 14,500.

There has been no parallel process, however, in France or Germany. When the original of this present volume was published by Editions Perrin of Paris in 2005, under the title Frres de Tranches (literally Brothers of the Trenches), each copy carried a striking wrap bearing the message Le Dernier Tabou de 1914: i.e. 1914s last taboo. The implication was clear; at last the story could be told or, in Frances case, it could now be admitted, the subtext being that there had been something shameful about French soldiers fraternizing with their German opposites while the latter were holding territory not their own, territory constituting part of la patrie, the sacred soil of France. But with the admission there was a sense of confidence that the event could now be interpreted in a new light. No longer forgotten, or unacknowledged, as in the old world of bitter national hostility, it could be revealed to a new generation in a new Europe as evidence of a step forward in terms of international understanding and reconciliation.

In Germany, the subject also remained dark for many decades, until a distinguished journalist and author, Michael Jrgs, raised the curtain on it with the publication of a book on the subject in 2003. Issued under the imprint of Bertelsmann of Munich and entitled Der Kleine Frieden im Grossen Krieg perhaps best translated as The Little Peace in a Big War the book produced an amazing response. Jrgs, whose researches I had the privilege of assisting in respect of the British participation in the truce, reported on its impact in glowing terms: The reception in Germany was just overwhelming. The book received wonderful reviews in Die Zeit, the Faz and the Tagespiegel and was featured in numerous TV programmes. However, the most moving reactions came when the author went on a ten-day lecture tour during which he found himself facing, as he put it: mixed audiences of young and very old people. The young ones asked question after question because their grandfathers and great-grandfathers never talked about the Great War and of course not about the Christmas Truce (which everybody thought to be UN-GERMAN behaviour), and the old ones could not hide their tears when I was reading because they had in their minds the memories of the Second World War and now, old enough, got the message from my book; that all wars are against humanity, against dreams, against hope, against the human race no matter which nation.

In the wake of such developments, it could be said that the subject was ripe for further exploitation. This present book, however, owes its existence not to a spread of interest among journalists, historians or the media, but to the intuition and vision of a young French film director, Christian Carion, a native of northern France, who somehow stumbled across the story which had taken place more or less on his own doorstep and saw the possibility of making a major film about it.

), but not as here where we had a German tenor and a Swedish soprano, symbolically singing between the lines in the cause of peace, having earlier been shown making love behind the lines presumably in the cause of humanity. The world might be bent on self-destruction but life must go on.

Despite its bold inaccuracies and certain other liberties that had been taken with the story, I admired and approved of the film, though I have to admit it was not a great success in Great Britain; somehow we dont do war in this way. The French, however, were sufficiently proud of it to make it an official entry for an Academy Award. It won no prizes but it was a worthy, honourable and brave production which I shall long remember.