Pagebreaks of the print version

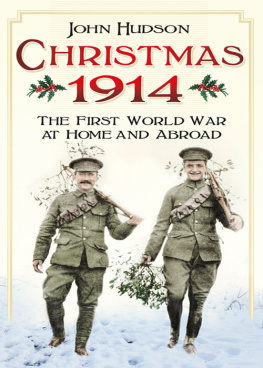

THE TRUE STORY OF THE CHRISTMAS TRUCE

THE TRUE STORY OF THE CHRISTMAS TRUCE

British and German Eyewitness Accounts from the First World War

Anthony Richards

Introduction by Hew Strachan

The True Story of the Christmas Truce:

British and German Eyewitness Accounts from the First World War

Greenhill Books

First published by Greenhill Books, 2021

Greenhill Books, c/o Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

For more information on our books, please visit

or write to us at the above address.

Copyright Anthony Richards, 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78438-614-6

eISBN 978-1-78438-615-3

Mobi ISBN 978-1-78438-615-3

for Malcolm

Illustrations

Pope Benedict XV (18541922)

Field Marshal Sir John French (18521925), commander of the British Expeditionary Force.

General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien (18581930), commander of the British II Corps and, from 26 December 1914, Second Army.

General Sir Douglas Haig (18611928), commander of the British I Corps and, from 26 December 1914, First Army.

Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria (18691955), commander of the German Sixth Army.

German soldiers singing carols in their trench, alongside a lit Christmas tree.

A typical German Christmas card from 1914.

This British Christmas card from 1914 stresses the partnership of the Allied nations.

Soldiers at the front would use whatever means they could to get a message home to their loved ones. This soldier chose to send home an annotated luggage label as a novel souvenir.

Around 400,000 gift boxes such as this were distributed to the British troops at Christmas 1914 on behalf of Princess Mary.

The Illustrated London News of 9 January 1915.

An internal illustration from the same journal gives an artists depiction of the fraternisation.

Press coverage of the truce featured many photographs taken at the front by the participants.

The Daily Mirror of 8 January 1915.

Many commemorative coins were struck to mark the First World War centenary in 2014, including this Christmas Truce example. It is unfortunately based upon an original photograph incorrectly attributed to the infamous football match!

This modern memorial to the truce, All Together Now by Andy Edwards, is located in the grounds of St Lukes Church, Liverpool.

Introduction

Itll all be over by Christmas.

S UCH WAS THE WIDELY shared hope held by many families in August 1914, at the very beginning of the First World War. Some kind of European conflict had been far from unexpected, with the increased militarisation of Imperial Germany threatening the fragile balance of power between European nations. The network of political and military alliances that existed between countries, built up over many years, meant that once a conflict broke out it would irrevocably draw in multiple combatants, along with their empires, ensuring that any war would become a truly global phenomenon. Yet few expected a war to last for so long. In the minds of many observers from both sides, it felt natural to expect a relatively short, sharp conflict, centred in Europe, in order to resolve the territorial disputes rather than anything longer term. Few if any would have predicted that the war would continue for another four years.

When Christmas arrived in 1914, barely four months after the outbreak of war, it proved to be an important moment for each nation to pause and process how the circumstances were affecting individual lives. As with any Christmas holiday, it was a time when everybody wanted to let off steam, to forget the difficulties they had been experiencing in everyday life and concentrate instead upon the need for selfish indulgence. The approach of the years end was also the traditional time for reflection on the previous twelve months, leading people to consider their priorities and hopes for the future. Yet this particular years Christmas celebrations would be affected by one very significant factor: the major European nations were fighting a brutal war. How could people really celebrate the season of goodwill during a time of hateful, bloody conflict? Christmas would no longer be the peaceful holiday that everybody expected, since world events had overtaken any individual concerns. But it gave people from both sides an opportunity to reflect on the reasons why they were fighting, and the likelihood of the war being resolved in the immediate future.

Some, including those not yet quite convinced of the likely prospect of an extended conflict, looked to Christmas as an excuse for accelerating peace. The First World War would see an unprecedented level of civilian debate which can be observed quite clearly in the newspapers and magazines of 1914 and remains crucial for understanding how people felt about the conflict at the end of that year. The expansion of war reportage brought the fighting directly into the living rooms of those back home, where people would debate the course of the war, offer praise to military heroes of the hour and circulate stories (often of dubious reliability) concerning enemy atrocities and their opponents overall beastliness. Everybody had an opinion and the all-encompassing nature of the war meant that there was an eager audience ready to listen. Thus by the end of the year a number of initiatives for peace had already appeared which, although ultimately unsuccessful, meant that the idea of a Christmas armistice was certainly in peoples minds as a possibility, albeit remote.

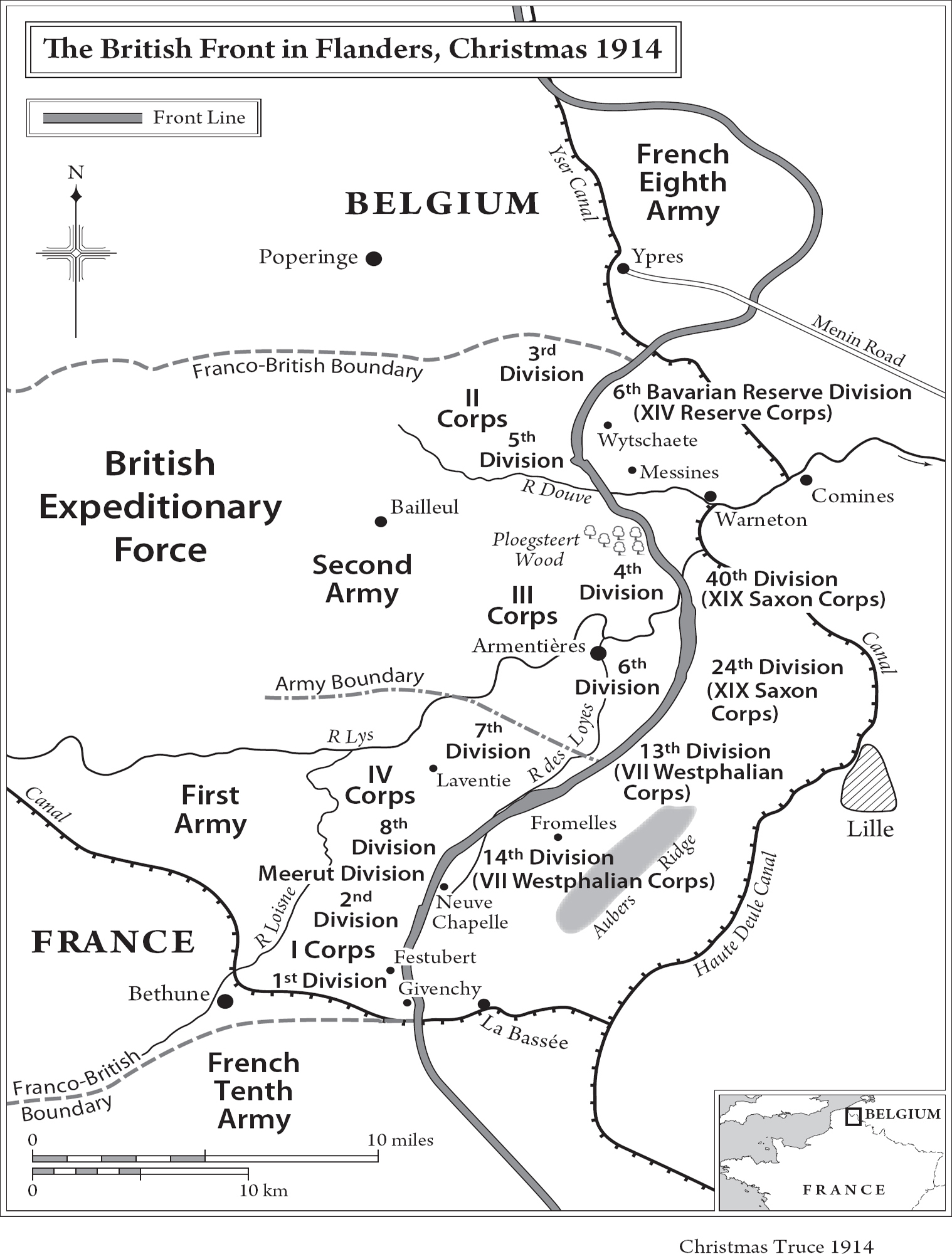

One of the most important factors which made that first Christmas of the war so different from Christmases of previous wars was the great number of men serving overseas. Earlier conflicts had largely been fought by professional armies, highly regimented and trained to obey orders, trusting in their military hierarchy to make the right winning decisions. But the need to expand the initial peacetime British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of 70,000 men to cope with the greater scale of the challenge on the Western Front meant that for the first time a significant number of soldiers serving overseas were from the Territorial Force: keen volunteers, known as weekend soldiers, who most likely had never suspected that they might be called to carry arms against an enemy in a foreign country.

Many families would therefore come together to share their Christmas dinner in 1914 with an empty place at their table for the first time; from Britain alone, by the end of the year some 270,000 men were serving overseas as part of the BEF while thousands more were already in the enemys hands as prisoners of war. In addition, almost 27,500 had made the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of their country and would never be returning home. This sense of separation either temporary or permanent would have been palpable in the last few months of 1914, and Christmas only made it worse. Those on the home fronts of both Britain and Germany would soon realise that the war was going to run and run, with no obvious end in sight.