First published in France in 1971

This translation first published in Great Britain 1975

by the Elmfield Press

This edition published in 2014 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street

Barnsley

S. Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright 1975 The Elmfield Press

ISBN 978 1 47382 298 6

eISBN: 978 1 47384 125 3

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England by CPI Group (UK) Ltd., Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, and Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact:

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England.

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

List of Plates

Introduction

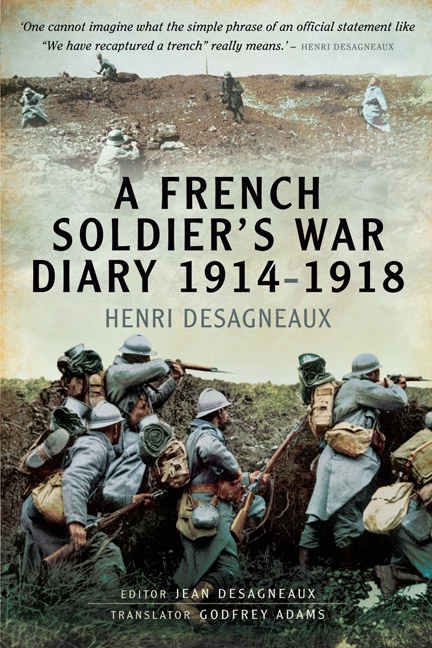

It may appear unwise to publish a new work retelling the story of the First World War when almost everything seems to have been said about it and the event has become distant in our minds. However, Captain Desagneaux writes, one cannot imagine what the simple phrase of an official statement like, We have recaptured a trench really means. It is precisely so that these words should no longer hide reality but show it in all its force, that this diary should be read. At the same time, the reader will discover that the First World War is not only that terrible holocaust with symbolic names like Verdun and the Chemin des Dames, etc., but a pattern of events which might seem comical, if they were not heartbreaking and too often tragic, due to the pettiness of military life, to the cowardice or blindness of certain leaders, to the bitterness which led to the mutinous revolts of 1917 throughout France. Like the Private, the reader sometimes desires to get back to the trenches and often ends up wondering what is the most deadly, the Front or the Rear?

Finally, fifty years after the event, these pages are the testimony of a man, of a race of men, who, because society and its moral principles, consciously or unconsciously, have changed, will scarcely be met with again.

It is not our intention to sit in judgement or to establish comparisons which are, after all, a matter of individual conscience. But it is obvious that a sense of patriotic duty pushed to such a degree of sacrifice, so much courage allied with so much modesty, so much honesty and uprightness even when confronted by stupidity and absurdity cannot but be remarkable. One can see in this diary as events proceed the birth of a new mentality which is not that of the author. This may appear justified, perhaps even necessary, but it certainly does not possess either its nobility or its grandeur. For two reasons, however, we do not desire to sing further the praises of a man whom you will discover in spite of his discretion and natural modesty: firstly, because this account, by its words and its silences, is a sufficient testimony for him; lastly, because I would not wish to be seen lacking in tact about a man who had so much himself, whom I deeply admire, who was my father.

JEAN DESAGNEAUX

1914

1 August , Saturday

From the early hours, Paris is in turmoil, people still have a glimmer of hope, but nothing suggests that matters can now be settled peacefully. The banks are besieged; one has to queue for two or three hours before getting inside. At midday the doors are closed leaving outside large numbers of people who will have to leave on the following day.

In front of the Gare de LEst, the conscripts throng the yard ready for departure. Emotion is at its peak; relations and friends accompany those being called up individually. The women are crying, the men too. They have to say good-bye without knowing whether they will ever return.

At last at 4.15 in the afternoon, the news spreads like wild-fire, posters are being put up with the order for mobilization on them! Its every man for himself, you scarcely have the time to shake a few hands before having to go home to make preparations for departure.

Its 5 oclock, my mobilization order states: first day of mobilizationwithout delay. The first day is 2 August!

2 August , Sunday

Mobilized as a reserve lieutenant in the Railway Transport Service, I am posted to Gray. At 6 in the morning, after some painful good-byes, I go to Nogent-le-Perreux station. The train service is not yet organized. There are no more passenger or goods trains. The mobilization timetable is now operative but nobody at the station has any idea when a train is due.

Sad day, sad journey. At 7 a.m. a train comes, it arrives at its terminusTroyesat 2 p.m. I didnt bring anything to eat, the refreshment room has already sold out. The rush of troops is beginning and consuming everything in its path. Already you find yourself cut off from the world, the newspapers dont come here any more. But, on the other hand, how much news there is! Everyone has his bit of information to telland its true! A squadron of Uhlans has been made prisoner; the 20th Corps is already in Alsace. Everyones talking about a Turpin Powder the effects of which are supposed to be devastating.

At last in the afternoon I catch the first train which comes along: a magnificent row of first-class carriages (a ParisVienna de-luxe; all stock is mobilized) which is going no one knows precisely where, except that it is in the direction of the Front. The compartments and corridors are bursting at the seams with people from all classes of society. The atmosphere is friendly, enthusiastic, but the train is already clearly suffering from this influx from every stratum of society! The blinds are torn down, luggage-racks and mirrors broken, and the toilets emptied of their fittings; its (typical) French destruction.

At midnight, I am at Vesoul; nothing to eat there either; no train for Gray. I go to sleep on a bench in the refreshment room.

The most fantastic rumours are going around; everyone is seeing spies unbolting railway track or trying to blow up bridges.

3 August , Monday

At 4.28 I leave Vesoul and arrive at last at Gray at 6.30 a.m. where I put myself at the disposal of the commander called Mennetrier. I am sent to Thaon station to see to the detraining of the troops.

The Eastern Railway Company is a source of admiration to everyone, but we are not used to such slow speeds. (The average for a military train is 25 kilometres an hour.)

Morale is excellent, everyone is extraordinarily quiet and calm. Along the track at level-crossings, in the towns, crowds singing La Marseillaise gather to greet the troops.

The French women have set to it. They are handing out drinks, writing paper, and cigarettes. The general impression is the following: its Kaiser Bill who wanted war, it had to happen, we shall never have such a fine opportunity again.

I dont stay long at Gray. At midday I catch the train again, am at Vesoul at 2.30, at Epinal at midnight. The area is already full of soldiers and there are no provisions to be found.