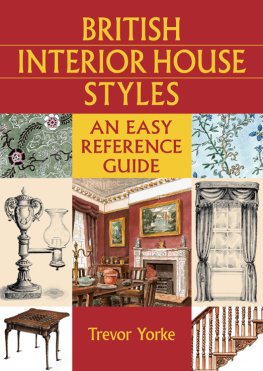

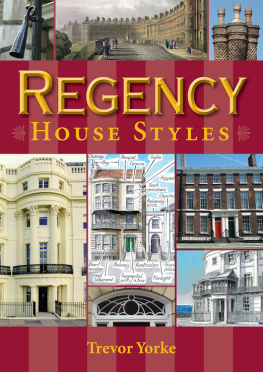

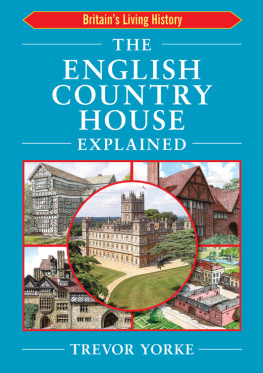

BRITISH

INTERIOR HOUSE

STYLES

Trevor Yorke

COUNTRYSIDE BOOKS

NEWBURY BERKSHIRE

First published 2012

Trevor Yorke 2012

All rights reserved. No reproduction permitted without the prior permission of the publisher:

COUNTRYSIDE BOOKS

3 Catherine Road

Newbury, Berkshire

To view our complete range of books, please visit us at

www.countrysidebooks.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 84674 300 9

Illustrations by the author

Designed by Peter Davies, Nautilus Design

Produced through MRM Associates Ltd., Reading

Typeset by CJWT Solutions, St Helens

Printed by Information Press, Oxford

C ONTENTS

Introduction

T he interior of a period house can reflect more than the style of its last make over. The richly figured oak panels of a timber-framed hall, the graceful and delicate plasterwork of a Georgian drawing room or the intense colour and clutter of a Victorian terrace have, in their fixtures and fittings, clues to the character, ambition and taste of previous occupants. The form of the room, its position within the house and the shape of its finer details can help to unravel the development and original date of interior spaces. Unlike the exterior of the house, where the huge expense of major changes limited drastic updating, the interior was prone to regular redecoration and fitting out with fashion able new furnishings, sometimes creating an eclectic mix of old and new, or completely covering up earlier details.

Underlying the bewildering range of styles and the whims of individual householders are some general changes in form, materials and fashions which can help the untrained eye to recognise the age and period of a room and some of its furnishings and fittings. It might be the type of wood used, the profile of a cornice or the colours in a wallpaper that give a clue to when that piece was first fitted. There are also small details which can help identify original parts from the wealth of imitation and reinserted furnishings and fittings which our predecessors especially in the 19th century were all too keen to use. For instance, old oak wall panelling was often removed and fitted into new properties but with little attention paid to the finer details of its construction. So, the flat chamfer which was always along the bottom edge of original pieces to make dusting easier can be found up the side or along the top where it has been moved. In this book, it is these general themes and characteristic details which are focused upon to empower the reader to recognise the popular styles and the period in which they were applied.

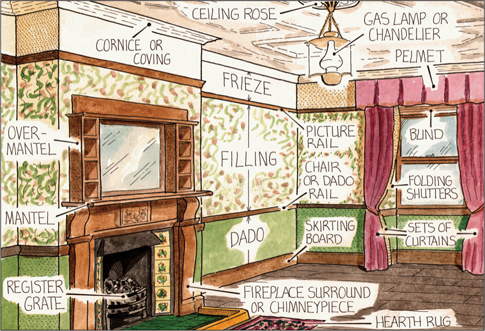

By using over 200 individual colour drawings and black and white sketches, the book illustrates the changing face of domestic interiors and introduces the key styles of fixtures and fittings over the past 500 years. Each chapter covers a consecutive period and works from examples of complete rooms down to details like furniture and lighting, with the accompanying captions highlighting the details and giving additional clues to look out for. Whether you would just like to know the background to the period houses you visit, want to know more about an old house you own or are trying to recreate or restore an historic interior, this book will provide an easy-to-follow introduction to the subject.

Before we race back 500 years, it is worth noting the limits of cramming so much history into such a short space. For simplicity, the dates of each chapter have been rounded up; therefore they do not mark the exact date of a change of monarch or style. Illustrations are used to include numerous important aspects of a style; as a result only a few of the drawings are of actual rooms but are rather suggestions of what they may have looked like. With the earlier periods, most of what we know comes from pattern books, illustrations and writings, less so from actual discoveries, so the colours and designs used show how an interior may have appeared rather than a definite scheme.

It is also important to remember when looking through this book or visiting a house over a couple of hundred years old that, on the whole, what you are looking at are the homes of the better-off members of a community, who even at the beginning of the 20th century represented less than a quarter of the population. What we regard today as a narrow terrace or Tudor timber-framed cottage was in its day an imposing house of a successful merchant or yeoman farmer. Few of the single storey houses which the majority of the working population lived in before the Industrial Age have survived, and most of the poor quality terraces which housed them during the Victorian period were swept away during 20th-century redevelopments. Their interiors would have been quite Spartan, with very few possessions, and it was not until mass production and cheaper materials from the late 19th century that style would have become an issue in their homes.

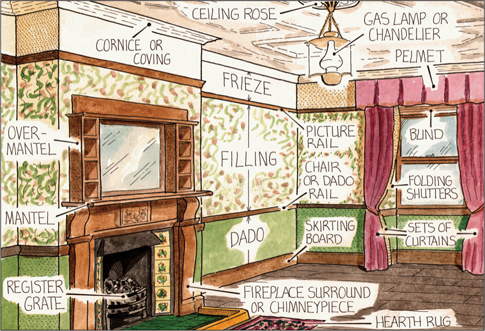

FIG 0.1:A living room with labels of key elements of the interior.

It was the gentry who were the trendsetters of their day, with a class below of professionals, merchants and farmers who emulated the latest fashions, those in cosmopolitan areas in the following years, others in more remote parts in the following decades. As this book focuses upon the buildings which you can visit or own, the earliest interiors which are featured will be from houses of the wealthy; by the second half of the 18th century it will include those of middle-class professionals; but only when it reaches the late Victorian period will it be representative of a wider proportion of the population.

Trevor Yorke

Chapter

Tudor and Jacobean Styles

15001660

FIG 1.1:An Elizabethan interior from a luxurious urban house, with the owners wealth displayed in the oak wall panelling, elaborate fireplace and decorative plastered ceiling. Furniture was limited but wall hangings, bold fabrics and splashes of paint made the finest rooms colourful places.

O ur journey through the history of English house interiors begins some 500 years ago when Henry VIII had recently ascended the throne. Over the following century and a half, up to the end of the Commonwealth in 1660, our domestic surroundings had begun a transformation from one based around a communal open hall to an arrangement of private rooms separated from the owners household. This key change was already underway at gentry level when we join the story and was still taking place lower down the social scale at the end of this period. A key element was the adoption of the fireplace and chimney set in a side wall, as opposed to the previous variety of arrangements where the hearth was within the body of the room. This change enabled a floor to be inserted above the old open hall, usually forming a great chamber in the largest houses where the family could take their meals and entertain guests; while the household who had formerly shared this daily routine were now relegated to the old hall below. In the smaller homes of the merchant or yeoman farmer this two-storey plan, with bedrooms above a living room and parlour, was widely adopted; in some wealthy areas like the wool rich Suffolk towns, this happened from the beginning of this period, whilst elsewhere it became common from the later 1500s as rising incomes sparked a Great Rebuilding of houses.