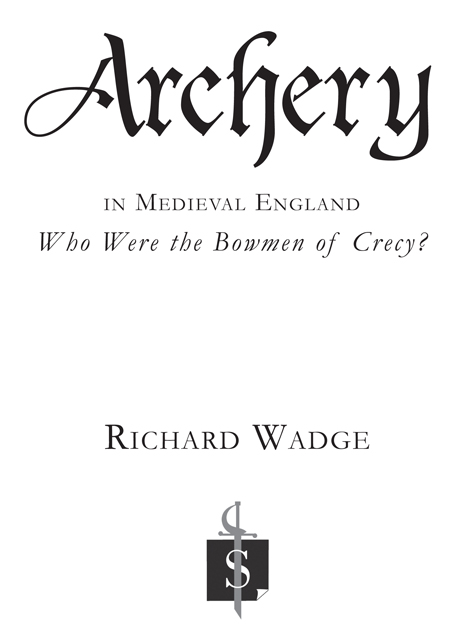

Richard Wadge - Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy?

Here you can read online Richard Wadge - Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy? full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: The History Press, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy?

- Author:

- Publisher:The History Press

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy?: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy?" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Richard Wadge: author's other books

Who wrote Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy?? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy? — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy?" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

M any people help an author towards the completion of the particular pet project in hand. What virtues this book has are made greater by the generous assistance I have received from many people. All the members of the English Warbow Society (EWBS) have helped through their commitment to English traditional archery. Steve Stratton, Mark Stretton and Glennan Carnie have been particularly generous with their time and thoughts.

While researching the book the staff of the Bodleian Library in Oxford have been particularly supportive through their cheerful professionalism. Anne Marshall of www.paintedchurch.org generously supplied photographs of church wall paintings. This website will be of interest to anyone who loves medieval history. Dr Mark Redknap and Sian Iles of the National Museum of Wales willingly gave of their time to allow me to look at arrowheads in the museums collection. The volunteer staff of Gloucester Cathedral particularly Patrick ODonovan were very supportive. Sarah Walter at the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne, Christine Reynolds, Assistant Keeper of Muniments at Westminster Abbey and Catherine Turner and the library staff at Durham Cathedral have been very helpful.

Finally my thanks go to my son Edmund for asking very pertinent questions about the scope of the book one night in Australia and to Eleanor for her patience and support.

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

VIII |

IX |

X |

T he basic unit of currency in medieval England was the silver penny. There were twelve pennies to a shilling, and twenty shillings to 1 sterling. In addition, the mark was an official unit of currency used in fines and accounts worth 13/-4 d or 160 silver pennies. No mark or half-mark coins were issued in England in the medieval period.

The penny could be divided into fractions: half-pennies and quarter-pennies, known as farthings, were made by clipping pennies. Officially issued silver half-pennies exist, the earliest found dates to Henry Is reign, and silver farthings have also been found, with the earliest dating from Edward Is reign. The cut coins remained in use besides the officially issued small coins because silver half-pennies and farthings seem to have been too rare to be effective small change.

What was the silver penny worth? It is meaningless to convert it to its modern decimal equivalent, but it is very useful to give some idea of what it meant to men and women of the time. In the middle of Edward Is reign, archers and labourers could earn 2 d per day in the kings service. This was twice what an agricultural labourer might get paid, although the agricultural labourer would probably get a daily meal as well. A carpenters wage at the same time was about 3 d per day. Many other craftsmen earned a similar amount. A labourer would struggle to support a family on his wages, whereas a carpenter would not.

Most rural people expected to grow some or all of their food, whereas town dwellers often had less chance to do so. It is, however, difficult to get an idea of food prices at the level of individual loaves or weights of meat. Bread and ale prices were controlled by law from Henry IIIs reign onwards, in an attempt to ensure the staples of the medieval diet were affordable. At the end of the thirteenth century a hen seems to have been valued at about 1 d at the most more valuable for its eggs than as a meal.

B etween the Norman Conquest in 1066 and the ravages of the Black Death in 134850 the practice of archery among the ordinary people of England and Wales produced archers and bows of such power and capability that they became a significant factor in European history, to the amazement of contemporary chroniclers. This has been much discussed by historians, but no clear picture of popular archery in medieval England and Wales has emerged to explain how this came about. Archery is an activity that developed in nearly all cultures and peoples for millennia. The Australian Aborigines are the most significant exception to this. Examples of the traditional use of self bows of different lengths are widespread, and can be found throughout history in four continents until the last quarter of the previous millennium.

Archery had been practised in the British Isles for something like four millennia before 1066. Perhaps the earliest evidence of the significant use of archery in war was found during the excavations at the Neolithic fort at Carn Brea near Redruth in Cornwall. About 700 flint arrowheads were found, many of them Neolithic leaf-shaped heads, and the largest concentration was around the probable site of one of the gateways into the fort. While the excavator observed that it is impossible to guess the nature of the warfare evidenced by the arrowheads, he felt that it was almost certainly fighting among the various Neolithic communities of the area and that the assault on the fort took place at some point in the mid third millennium BC .

Despite this long history of popular archery in the British Isles, its use in warfare ebbed and flowed as various cultures arrived or developed. In general, although archery was used in hunting throughout the long period starting with the Neolithic period, it remained peripheral to the development of military practice. But some combination of circumstances after the irruption of the Normans into British history led to the development of both the skills and the equipment necessary for longbow archery to become a revolutionary change in Western European military practice. The three most commonly quoted reasons for this development are: the importance of archery in the Norman victory at Hastings, albeit using bows less than man height in length; the unpleasant experiences of Welsh archery suffered by both English armies in the decades before the Conquest and the Norman armies after it; and the Norse tradition of longbow archery in those parts of England and Scotland heavily influenced by the Vikings. But these factors alone arent enough of an explanation. All three applied in Ireland: Norse settlements; experience of the effectiveness of the Welsh archers; and military leaders who understood the usefulness of military archery. Yet the Irish themselves did not develop a military practice exploiting powerful hand bows despite their experiences on the receiving end of it. The Anglo Norman community in Ireland continued to develop military archery to the extent that there are records of companies of archers from Ireland being included in English royal armies in the fourteenth century. It most certainly was not for want of good bow wood in Ireland since yew bowstaves were imported from Ireland to England between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. One reason for the lack of development of archery in medieval Ireland was because the population of England at large seem to have practised archery for sport and hunting more commonly than was the case in Ireland in the Middle Ages.

But the evidence of what was going on in Ireland is very important, because Ireland has provided that rarest of archery-related archaeological finds, a medieval yew bow from before the Tudor period. One complete bow has been found that dates to the period of the Anglo Norman invasions of that island in the twelfth century.

An understanding of the development of popular archery in England of the twelfth, thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries can be built up by looking at the eclectic collection of records mentioning archery that have survived. These include court records of criminal activities; wills and inventories that show men owning bows; records of sports and pastimes; accounts of hunting, most of it illegal, and military archery. Archaeological finds are important because they show actual practice unfiltered by legal scribes, chroniclers or any other observer. But these are a bit one sided consisting almost entirely of arrowheads; finds of bows, arrowshafts and bone or leather archery accessories are very rare, as are finds of artefacts made of organic material in general. As yet there have been no finds of anything that might be archery butts confirmed for the period 1066 c .1350. Then there are all the statutes and orders that both encourage the ownership of bows and arrows and restrict their use. Artistic representations showing archers with their bows and arrows include manuscript illustrations, church wall paintings and a few carvings, but these come from a time before rigid representational art. Finally there are any records or events that give an insight into the value that was put upon archery skills. Taken together the activities described in these records and a study of the various artefacts make up a patchwork picture of popular archery before the successes of Edward IIIs reign made the practice of archery part of the nations self image.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy?»

Look at similar books to Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy?. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Archery in Medieval England: Who Were the Bowmen of Crecy? and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.