CASTLES OF CONQUEST

W hen Duke William of Normandy and his invasion fleet, perhaps consisting of 7,000 men, a third of them knights, with their horses, equipment and supplies, landed at Pevensey Bay in Sussex on 28 September 1066 he found a land already richly provided with fortifications, even if many of these were archaic. By the bay was the late third-century AD Roman fort of Anderida, part of a line of similar fortifications along the countrys south-eastern and eastern seaboard. A corner of the fort, cut off by a ditch and bank, provided the basis for a temporary camp for William. He then moved to Hastings where, again, a fortified camp secured his base (its precise nature remains unclear). This pattern would be repeated as the invasion force moved along the coast and inland, the Normans using ingenuity in making use of the walls of roman forts and cities, Anglo-Saxon burhs (part of a national system of defended towns), prehistoric hillforts and even neolithic mounds used as cores for Norman castle mounds. The defeat of King Harold the following month left the country leaderless and with its army destroyed. Thus began a process that would see England and South Wales covered in Norman castles both great and small.

Old Sarum, one of many ancient fortified sites utilised by the Normans: a ringwork has been raised in the centre of the prehistoric hillfort. A town and cathedral would later occupy the rest of the forts summit.

William and his knights, who excelled in the art of war, were part of an expansionist Norman elite that had already colonised southern Italy and Sicily. England would undergo a revolution, tying it more closely to the European mainland. The followers of William, soon to be bound to him by grants of land, would hold the land by ruthless means, their power bases being in the castles they built, many inserted into existing burhs to control and tax the lo cal population.

Subsequently, a number of Williams first conquests passed into the control of trusted and powerful knights and bishops. The means of securing a hold over the conquered country would be the castle: initially many of these would have been quickly erected circular earth and timber enclosures known as ringworks, often later replaced by the ubiquitous motte and bailey castle. Such castles, consisting of a mound (motte) topped by a palisade and tower together with a similarly palisaded bailey, had appeared in northern France before the Conquest and are depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry. In time many would develop into great fortresses and residences, some of which still remain in the hands of the original families, while others would be claimed back by the king or be passed on to his male offspring.

William the Conquerors White Tower at the Tower of London, so called because its surface was once rendered and limewashed. A modern wooden staircase replaces the vanished forebuilding.

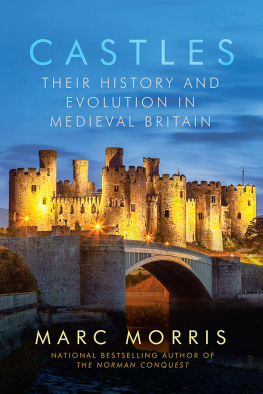

After securing his seaward bases at Pevensey, Hastings and Dover (at the latter using a prehistoric hillfort and Roman signal station site) and defeating Harold and his army, William moved inland towards London. Here he fortified a corner of the Roman city wall, later to be occupied by his great White Tower, and built two additional castles to secure his hold on the capital: Baynards and Montfichet. From London he moved to Norwich (1067), then Exeter (1068) and he subsequently moved northwards to Warwick, Nottingham, Lincoln, Huntingdon and Cambridge. By the end of his reign in 1087, besides the county town castles, many smaller castles had been built to secure his hold over the rest of England and parts of Wales. During his reign great, strong towers and halls of stone were beginning to appear, influenced by French examples such as the great tower at Loches; at Chepstow, the White Tower, Richmond and Colchester (using the massive foundations of the Roman temple of Claudius, destroyed during the Boudican revolt of AD 6061, and utilising the temples surrounding wall as the basis for its bailey), as well as new masonry walled enclosures such as those at Ludlow and Richmond in Yorkshire where river ravines provided additional protection. In addition to these began to appear the motte and bailey castle.

William fitzOsberns eleventh-century great tower at Chepstow; the remains of the additional storey are of a later date.

The massive great tower of Colchester, missing its uppermost storey, built on the foundations of a Roman temple and, with its chapel apse, resembling the plan of the White Tower.

These great stone towers and enclosures were atypical: most castles were of wood and earth resembling those portrayed in the Bayeux Tapestry. We have seen that the earliest new-build campaign castles were probably ringworks: deep circular ditches with the spoil formed into banks topped by palisades. Within, accessed by a gate, would be simple living accommodation and stabling. Where topography permitted it, a ditch and palisaded bank across a ridge could form the simplest of fortifications. The excavated Penmaen Castle Tower, Glamorganshire, is such an example: a small promontory ringwork by the sea with a gate tower and hall, of timber and drystone walling. Unlike masonry work, timber defences could be built rapidly and all year round (mortar could not be used in times of frost) and wood in lowland England and Wales was freely available. The disadvantages were that it was inflammable (the Bayeux Tapestry shows Williams soldiers attacking the rebel castle at Dinan with fire) and was subject to rot. Despite this, the substitution of masonry for timber was slow: for example, the keep on the motte at the major castle of Shrewsbury remained a wooden one until the latter part of the thirteenth century.

The wooden church at Greensted in Essex, a remarkable survival from the time of the Conquest.

The unique Greensted timber church in Essex, built at the time of the Conquest, gives an impression of how the timber walls of a Norman castle might have looked. To make the walls of the church tree trunks were split in half and trimmed to shape with an adze (a type of axe). All bark and perishable sapwood was removed. The original trees must have been of a considerable size. The half cylinders of heartwood were then set upright with their flat faces inward, morticed together to make a sturdy wall set in the ground.

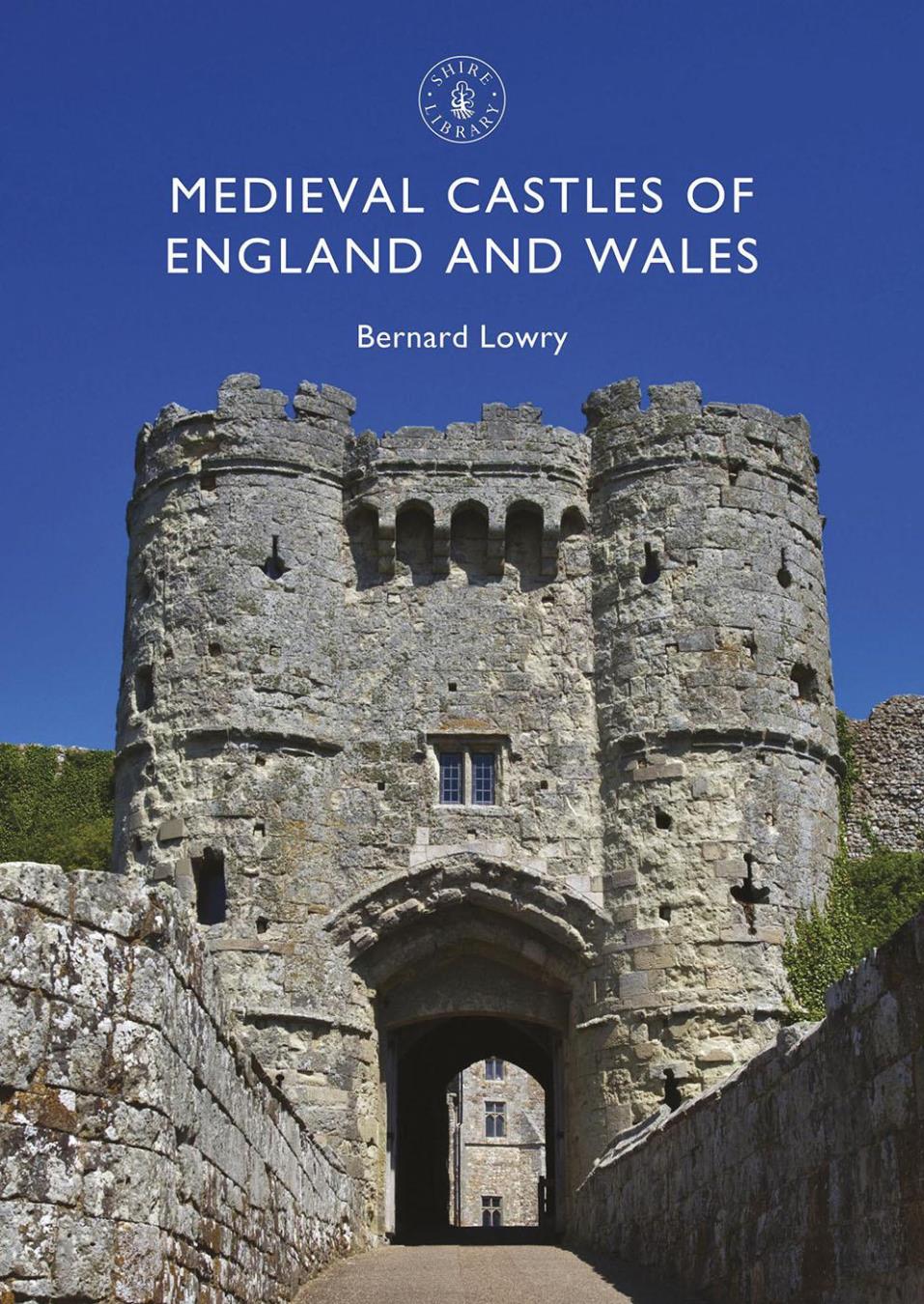

Ludlow, built as a stone castle in the late eleventh century, its (blocked) gatehouse later converted into a great tower. An original hollow wall tower can be seen on the far left.