Copyright 2015 by Edd Morris

Photographs copyright by Edd Morris unless otherwise noted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Jane Sheppard

Cover photo credit: ThinkStock

Print ISBN: 978-1-63220-348-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63450-009-8

Printed in China

Table of Contents

Introduction: A Note for Castle Explorers

A misty morning breaks over the ruins of Corfe Castle.

Like many of the greatest elements of modern-day Englandfrom loose-leaf tea to chicken tikka masala currycastles were a foreign import. The first of their kind arrived in England in 1051 and was built in rural Herefordshirea sleepy place thats, strangely enough, the county where I was born.

A beautiful tower within the Norman castle of Lewes, in East Sussex.

T his founding fortification was a design sensationimported directly from France, always a place of cutting-edge fashion. To our modern eyes, it certainly wouldnt have looked like muchit was likely just a mound of earth with scattered wooden fortifications across the top. Despite this, there would have been nothing comparable in Medieval England. As a result, its presence would have felt like an alien spaceship landing in the countryside. The contemporary chroniclers had no word for this new-fangled monstrosity, so they just plumped for the French term: they christened it a castle .

This castle was to be the first of many. Come 1066some fifteen years laterthe Normans would invade England from the continent and would build hundreds more of the things. Some would be built with care; others would be thrown together in haste. Either way, the Normans used castles to hold power over their conquered nation. These modern fortifications, in combination with devastating military skill and political cunning, meant that a force of just two thousand disciplined invaders commanded a nation of two million rowdy Anglo-Saxons, all in a matter of months.

Quite obviously, these first castles dont look at all like the castles of our imaginations. Indeed, if I asked you now to visualize a castle, I doubt youd dream of a muddy hillock topped with a timber fence. Over time, this fortification evolved, and the word castle began to mean something quite different. The 1100s and 1200s signified a special species of gray stone monster: a structure bristling with grand towers, great keeps, curtain walls, jagged crenellations, fortified gatehouses, and swinging drawbridges.

The alluring path through Coltons Gate, in Dover Castle. Just beyond lies the Great Tower.

The central question, then, is what makes a castle a castle? After all, the earthen mound and gray stone enclosure are superficially very different beasts, yet we use the same word for each. Essentiallyand Id be quick to emphasize that this is my opinion from my own explorations, rather than the result of a lengthy academic endeavorI believe a castle is an intriguing mix of high-status accommodation and hard-wrought defense. Those first Norman castles were called motte and bailey , where the motte was the defensive earth mound and the bailey was an enclosed courtyard for domestic use. Late medieval castles evolved to feature all those castle-y accoutrements we love so much (towers, arrow-slits, moats, and the like), but also housed grand tapestried rooms and gilded chambers fit for a king or queen.

The thick wooden door of Stokesay Castle in Shropshire.

Essentially, then, theres a tantalizing tension at the heart of a true castle. A castle isnt a fortress, and its not a stately home. Its somewhere on the spectrum between the two, combining military prowess with unimaginable luxury. To put it another way, its a place where you could sleep in a decadent four-poster one night and have your head chopped off and placed upon a spike the next (an eventful weekend, by any count). A true castle has a heady mix of violence and decadence, bloodshed and splendor, which is why, almost by definition, no real castle can ever be boring.

I should note, though, that many castles do carry an air of pretension. Building or refurbishing a castle would have been a devastatingly expensive exercise, suitable only for the grandees of early modern England. In return, an individual would have been blessed with a truly formidable status symbol; no one could doubt the societal standing of a man with a castle. In fact, the sheer appearance of a castle would have conveyed a great deal about its owner, his perceived self-worth, and his future aspirations.

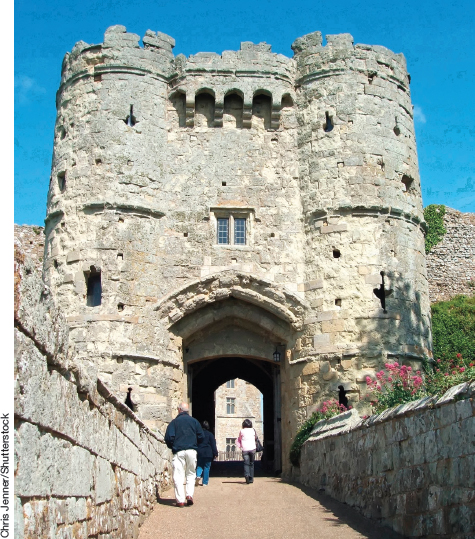

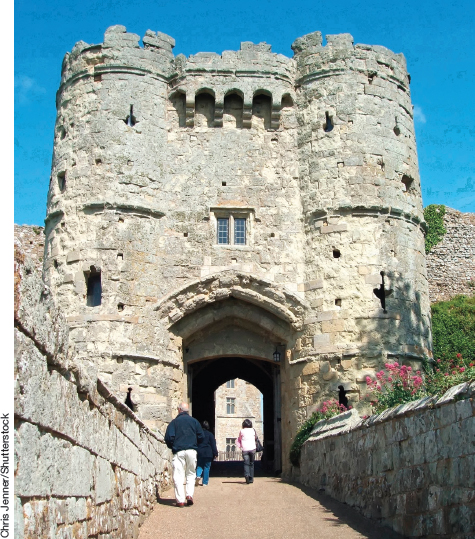

The gatehouse of Carisbrooke Castle, upon the Isle of Wight. The castle was founded in about 1100, but this gatehouse was built in the 1300s. The castle is most famous for being the prison of King Charles I after his defeat in the English Civil War.

As a result, do be warned: some English buildings that look distinctly castle-y can be a bit of a trick. Quite often, a social aspirant built what was really a grand house, and, with pretentions of greatness, disguised the outside with a few features of castle architecture to add a touch of ill-gotten grandeur. Consequently, Ive been somewhat selective about the castles featured in this book. Everything within these pages is authentically medieval and truly fit to be called a castle.

Ive also tried to approach writing about castles in a slightly different way. Many books about castles include a selection of fortresses and valiantly attempt to cover the thousand-year history of each one. Ive taken a different approach: rather than cover a swathe of history for each, Ive tried to take a snapshot of one of the most notable moments in the past: the Great Siege of Rochester Castle, for example, or when Queen Elizabeth visited Kenilworth. Hopefully this helps to bring some of the characters to life and also makes some of the underlying chronology a bit easier to understand.