Hadrians Wall was built by the Romans across a 70-mile stretch of northern Britain in the second century AD

What, then, is a castle? And how did this type of building come to exist and to play such an important role for centuries? To some extent, of course, castles speak of a universal human desire for security. Like other animals, humans have always sought to protect themselves. Even today we use bricks and mortar, wood, metal and stone to give ourselves some measure of protection from both the elements and other people. The earliest humans used the natural defences of the landscape: caves, mountain passes, rivers and swamps. Nearly 12,000 years ago Neolithic man built a massive stone wall to protect Jericho. Iron Age defensive structures ramparts and ditches remain clearly visible, particularly from the air. The Romans built walls, forts and camps right across their vast domain: an attempt to secure themselves against the incursions of barbarian tribes like the Saxons and the Franks.

In Britain it was the Anglo-Saxons who were the principal successors to the Romans, but they in turn came under pressure from without. Their response to the seafaring, warlike Vikings was to put their faith in fortifications. They built walls round important towns, creating defended settlements called Burhs (Wareham and Wallingford are well-preserved examples). In France, meanwhile, the Viking onslaught prompted people to build subtly different defences. It was here that a new kind of fortress appeared on the scene: the castle.

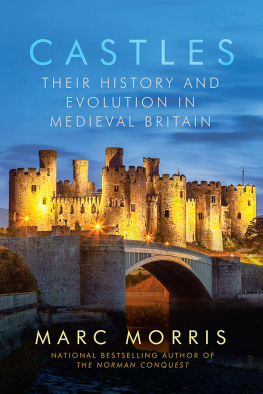

The word castle came from the Latin castellum, a term which simply meant any kind of fortified building or town. In English the word has come to describe the grand fortified residences of kings and lords. Most people agree that a castle was a combination of a fort, the residence of a lord and a centre of authority. However, in his excellent recent history book, The English Castle, John Goodall remarks that, a castle is the residence of a lord made imposing through the architectural trappings of fortifications. This gets round the tricky problem that many buildings that look like massive castles are actually lavish palaces; they look imposing, but are in fact militarily indefensible and not really forts at all.

Castles spread fast through a fragmented, violent Europe. In the 840s, Charles the Bald had just succeeded as King of the West Franks (a kingdom that was to morph roughly into modern France). He and his brothers were at each others throats as they wrestled with the problem of governing their grandfather Charlemagnes vast legacy, which stretched from the north of modern Spain through France, Germany and Northern Italy. They faced external threats: the spread of Islam in the Iberian Peninsula; the Vikings who raided deep inland, as far as Paris several times in the ninth century. Within, they faced the perpetual aggravation of a restless and independent-minded aristocracy, eager to bolster their position by building. It was in the midst of all this, in 846, that King Charles issued a historic order: We will and expressly command that whoever at this time has made castles and fortifications and enclosures without our permission shall have them demolished.

Neuschwanstein is a nineteenth-century palace in southern Germany with a castle-like appearance, built by King Ludwig II of Bavaria

Ingmar Wesemann / Getty Images

Charles was referring to strongly-fortified residences of the aristocracy. Initially they were simply strong houses, such as Doue-la-Fontaine in Anjou which was given much thicker walls and an easily defensible entrance on the first floor. In the region which would become the kingdom of England, homes of lords were not designed to withstand a determined onslaught the main fortifications were the burhs, communal defensive structures built by royal command. In France, by contrast, the local magnates responded to collapsing central authority by taking matters into their own hands. Government came to be exercized by the local lords. They issued coins, collected the taxes, defined and enforced the law. Every local warlord became a king, and kings needed grand fortified residences. Political authority was becoming fragmented and the architecture of the castle was the physical manifestation. The Italian word describing this breakdown of authority is