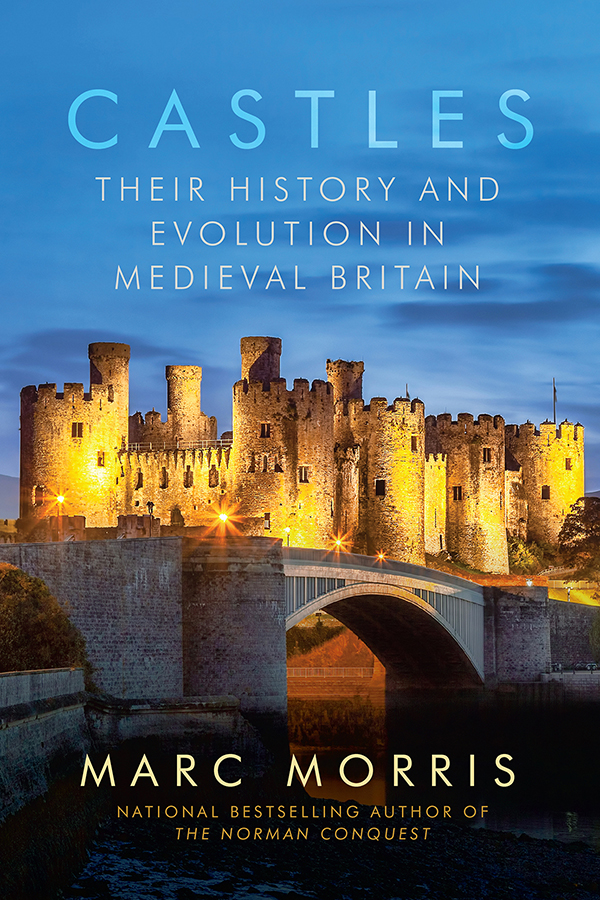

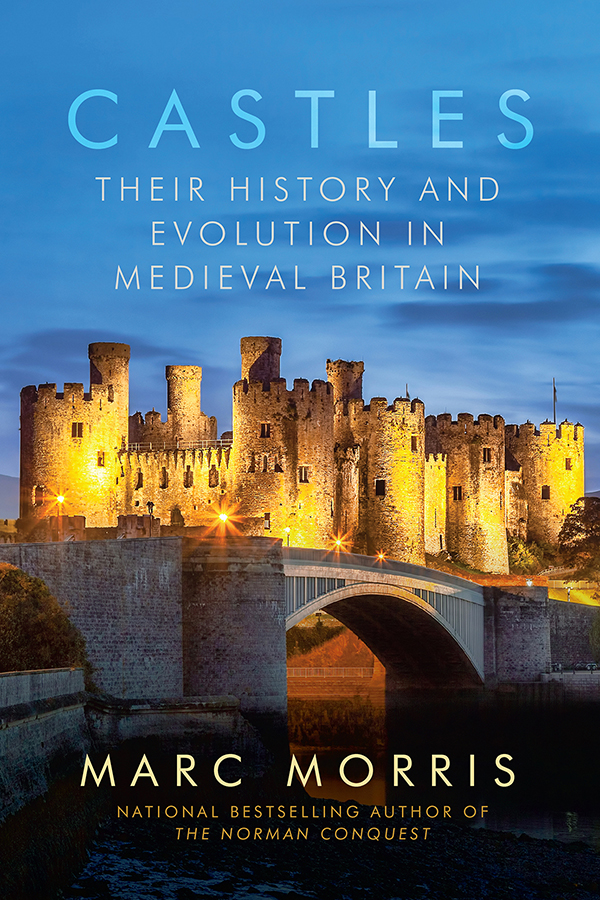

CASTLES

THEIR HISTORY AND EVOLUTION IN MEDIEVAL BRITAIN

MARC MORRIS

CASTLES

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2017 Marc Morris

First Pegasus Books cloth edition April 2017

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-359-9

ISBN: 978-1-68177-395-7 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

To my parents

who took me to a lot of castles

CONTENTS

T he county of Kent has more than its fair share of castles, and my parents and schoolteachers conspired to ensure that I was familiar with most of them from a young age. Not, you understand, that I needed much encouragementtrips to castles were always my favorite. Around every corner, through every doorway, there was the promise of fresh excitement. An over-imaginative little boy could easily picture knights in shining armor, damsels in distress, sieges, feasts and tournaments. Whether ruinous or restored, castles were magical places.

Or at least, most of them were. Some of them, Im sorry to say, I found a bit boring. Certain castles, I noticed, had lots of cannon, but nowhere for the king to eat his dinner. Others, by contrast, had plenty of fancy bedrooms, but nowhere for the soldiers to sleep. Either way, one or two of the castles I visited as a child seemed to lack certain important things, and I would return home a little disappointed, though for reasons I couldnt quite fathom. Clearly these buildings didnt measure up to my idea of what a castle should be.

So what is a castle? Is there a good definition? The Oxford English Dictionary helpfully tells us that the word itself derives from the medieval Latin word castellum , and ultimately from the classical Latin word castrum , meaning camp. A castle, it goes on to say, is a large building, or set of buildings, fortified for defense against an enemy; a fortress, stronghold. Many people, I think, would find nothing to disagree with in this statement. The word castle tends to conjure up images of boiling oil, bows and arrows, catapults and battering rams.

But is that all there is to it? Are castles just about fighting, or even self-defense? Havent the dictionary compilers missed an important point? On the outside of a castle, we expect to see drawbridges and battlements, portcullises and arrow-loops; but what about on the inside? There, surely, we expect to see evidence of luxury and creature comforts. There are great halls for banqueting, and huge kitchens to prepare lavish feasts; bedrooms, chambers, and chapels, all once sumptuously decorated; stables, granaries, bakeries, brewerieseverything, in short, that was necessary to make them perfect residences for their owners.

So a castle might be a fortress, but it is also, crucially, a home. This was the definition famously offered by Professor R. Allen Brown in his groundbreaking book, English Castles . From the moment it was first published in 1954, the book established itself as the most influential work on castles, and it is still required reading today for anyone even remotely interested in the subject. A castle, to quote Professor Brown, is basically a fortified residence, or a residential fortress. Castles were not simply buildings into which people retreated when the going got tough; they were places where people spent time willingly. When I read the book for the first time, I realized why certain castles had bored me as a boy; the less interesting ones had been either entirely military in purpose, or else they had no defensive capability at all. These so-called castles, it turned out, were really nothing more than forts, and mere stately homes. According to Browns definition, a real castle was a fortress and a stately home rolled into one.

For many medieval historiansmyself includedthis textbook definition of a castle seemed to fit the picture perfectly. It also explained why we love castles so much. For how can a building be warlike and homely at the same time? Luxury demands more space, thinner walls, bigger windows. Security, on the other hand, says keep everything crammed inside thick walls, and make the windows small. For castle designers, the major challenge was reconciling these two apparently contradictory imperatives. For castle enthusiasts, the ingenious ways in which they did so is part of what makes castles so endlessly fascinating.

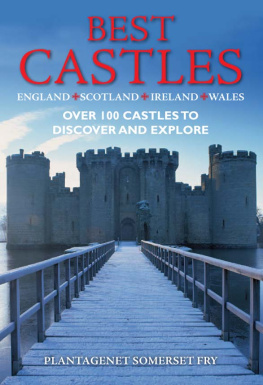

Recently, however, castle experts have begun to question this definition. The problem with deciding that a castle is a fortress and a home, they say, is that this excludes a lot of castles from the club. Take, for example, the subject of Chapter Fourthe gorgeous Bodiam Castle in Sussex. There is no doubt at all that this was once a classy home for a rich aristocrat. But did its owner ever intend to use it as a fortress? Most of the exterior features (as we shall see) seem to be just stuck on for effect. The moat, the battlements, and the portcullises, all of which might suggest we are dealing with a formidable stronghold, are in actual fact all highly suspect. If Bodiam had ever ended up in a really serious fight, chances are it would have been quickly clobbered into submission.

So does this mean that Bodiam, and other similarly weedy castles, are not really castles at all? The answer must surely be no. We can call Bodiam a castle because... well, because it plainly looks like a castle. And, more importantly, the people who were around when Bodiam was built also called it a castle: it would be very arrogant of us in the twenty-first century to disqualify Bodiam on the grounds that we knew better than they did. Clearly it is not Bodiam Castle that is the problemit is our definition. None of the castles Ive visited recently seem to be having an identity crisis, but some of the experts Ive encountered have grave doubts. Professor Matthew Johnson has just concluded his new book by confessing that he is less certain than ever about what castles really are.

And yet, in spite of the uncertainty among historians, there still seems to be a general consensus about which buildings are castles, and which ones are not. What we no longer have is an easy, no-nonsense, one-size-fits-all definition. This, of course, makes it tough if you find yourself writing a book on castles, because, as R. Allen Brown rightly said, Any book about castles should begin by saying what they are.

So, with this advice in mind, heres what I think. A castle was first and foremost a home to its aristocratic owner and his or her household. That, I believe, must be our starting point. Down to the end of the thirteenth century in England, and slightly later in Wales and Scotland, these noble residences were also strong, defensible buildings that we can reasonably describe as fortresses. Some of the castles in this book wereindeed, aretremendously tough buildings, designed to withstand the most deadly assault weapons of the Middle Ages. From 1300 onward, they could afford to be less effective at keeping people out, even to the point of not being defensible at all. But, as with Bodiam, what made a castle was not how tough it was, but whether or not it looked like one. In order to be considered a castle, a building had to have at least some of the physical attributes that contemporaries associated with castles, such as battlements, portcullises, arrow-loops, and drawbridges. Whether they actually worked or not was irrelevant. They were still essential, because they had come to symbolize somethingthat the people inside were important, that they had a right to rule others, and that they expected deference, obedience, and respect.

Next page