King John

TREACHERY and TYRANNY

in MEDIEVAL ENGLAND:

The Road to Magna Carta

MARC MORRIS

To William

my treasure

Contents

I n Johns day (and indeed until the currency was decimalized in 1971), money in England was measured in pounds, shillings and pence: twelve pennies made a shilling, and twenty shillings made a pound. The only type of coin in circulation was the silver penny, so a pound was a weighty bag of 240 coins. The average income for a baron was about 200 per annum, and even a man who took home 20 a year would have been considered quite well-off. Money was also counted in marks, which were equivalent to 160 pennies, or two-thirds of a pound.

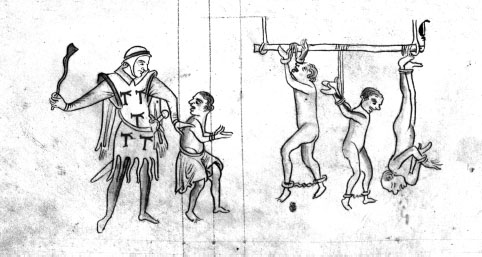

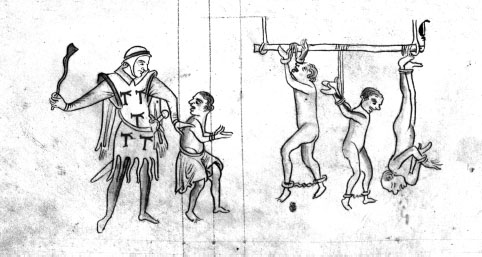

People being tortured during the reign of King John. A drawing by the thirteenth-century chronicler Matthew Paris.

1. Torture during the time of King John. Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. MS 16, f.48v.

2. Chteau Gaillard and the Isle of Andely today. Robert Harding Picture Library/John Miller.

5. Tomb effigy of Eleanor of Aquitaine. akg-images/Erich Lessing.

6. Tomb effigy of William Marshal. Temple Church, London, UK/Bridgeman Images.

17. King Johns tomb. JTB Photo/UIG/Getty Images.

I n the summer of 1797 a group of workmen in Worcester Cathedral caused a sensation, locally if not nationally, by discovering the body of King John.

Johns tomb had long stood in the middle of the cathedrals choir, but the consensus view in 1797 was that it was empty. Although the stone likeness (or effigy) on top dated from not long after the kings death in 1216, the tomb chest had been created in the sixteenth century in the style of more recent burials (most notably Henry VIIIs older brother, Arthur, who died in 1502). It was known from the testimony of ancient chronicles that John had been buried in the Lady Chapel, and so it was assumed that, although his effigy had been moved in Tudor times, his bones had been left undisturbed in their original resting place.

The cathedral clergy found Johns tomb a cause of much annoyance, because its central position obstructed the approach to the altar, and their plan was to move it to some more convenient part of the church. And so, on 17 July 1797, the workmen set about dismantling it. They removed the effigy and the cracked stone slab underneath, to discover that the chest had been partitioned by two brick walls, and the sections in between filled with builders rubble. But when they removed the sides of the tomb and cleared out the debris, the workmen, to their astonishment, found a stone coffin. Immediately the dean and chapter of the cathedral were convened, as well as some local worthies with relevant expertise (the antiquarian Mr James Ross, and Mr Sandford, an eminent surgeon of Worcester).

Inside the coffin they found the entire remains of King John. His corpse had obviously decomposed somewhat in the course of nearly six centuries. Despite being embalmed, some parts had putrefied, and so a vast quantity of the dry skins of maggots were dispersed over the body. Parts of the body had also been displaced, presumably when it was moved in the sixteenth century. A section of the left arm was found lying at an angle on the chest; the upper jaw was found near the elbow. But otherwise the king was arranged in exactly the same position as his effigy, and was similarly attired. He was dressed from head to foot in a robe of crimson damask (a rich fabric of wool woven with silk) and in his left hand as on the effigy he held a sword, in a scabbard, both badly decayed. Curiously, however, whereas on the effigy John wore a crown, his skull was wearing a coif, which the antiquarians took to be a monks cowl, placed on the kings head after his death to help reduce his time in Purgatory. Measuring the body they found that John had been five foot six-and-a-half inches tall.

The experts might have continued their investigations further, but were prevented from doing so by a large number of people who had crowded into the cathedral to see the dead monarch. It is much to be regretted, explained the antiquarian Valentine Green in his published account of the exhumation, that the impatience of the multitude to view the royal remains, so unexpectedly found, should have become so ungovernable, as to make it necessary to close up the object of their curiosity. He was not exaggerating. In the short time that the tomb was open, several bits of Johns body were removed by souvenir hunters. His thumb bone was later recovered and can now be seen in the cathedrals own archives, along with some fragments of sandals and stocking, obtained at auction by Edward Elgar. Two of the kings teeth, stolen by a stationers apprentice in 1797, were secretly treasured until 1923, when they were handed over to the Worcester County Museum.

* * *

It is easy to understand the excitement of the people of Worcester in 1797. King John is one of those characters from English history who has always exerted a hold on the publics imagination. Almost everyone, even if they know nothing else about the Middle Ages, must feel they know something about him. Unlike other famous medieval monarchs, this is not down to Shakespeare, whose Life and Times of King John is one of his worst (and hence least-performed) plays. We are introduced to John much earlier, as children, through the tales of Robin Hood. My own introduction to him, Im sure, was Disneys Robin Hood , released in 1973 (the year I was born), in which the king, voiced by Peter Ustinov, is memorably portrayed by a scrawny lion, with a head too small for the crown he has pinched from his older brother, Richard the Lionheart.

As we will see, there is an element of truth in this story John did at one point try to usurp the throne from Richard. But the association of John with Robin Hood is pure fiction. The tales of Robin Hood were not written down until the fifteenth century, and in their earliest versions they are said to take place during the time of King Edward. It was not until the sixteenth century that a Scottish writer, John Mair, thought to relocate them to the reign of Richard the Lionheart. From that point, however, the association of John and Robin took firm root. The story was given an immense boost by Walter Scott in his 1820 novel, Ivanhoe , which became the basis for the celebrated 1938 Errol Flynn film, The Adventures of Robin Hood , itself the basis of the Disney animation.

To get to the real King John, we have to look at the evidence from his own day what was said about him by contemporary chroniclers, and what can be learned about him from official records. Johns reign was a watershed moment in many important respects, including the amount of government archive. From the time of his accession in 1199, the kings chancery, or writing office, began to keep copies of the documents it produced by enrolling them, and these rolls have for the most part survived. (They are now housed in the National Archives at Kew.) As a result we have far more letters, charters, memoranda in short, far more information about John than we do for any of his predecessors. Most of the time we can see where he is, who he is with, and what is on his agenda.

Next page