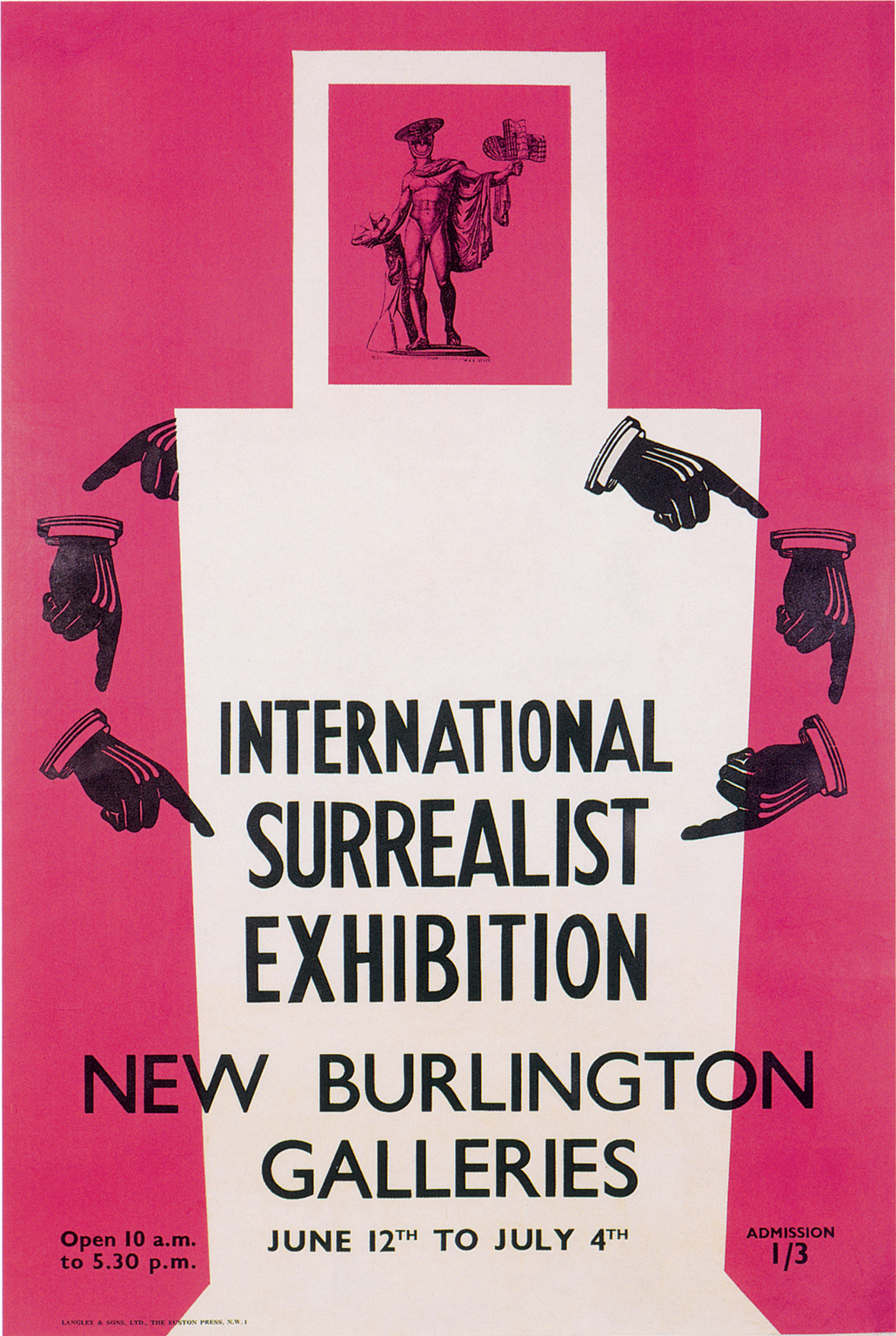

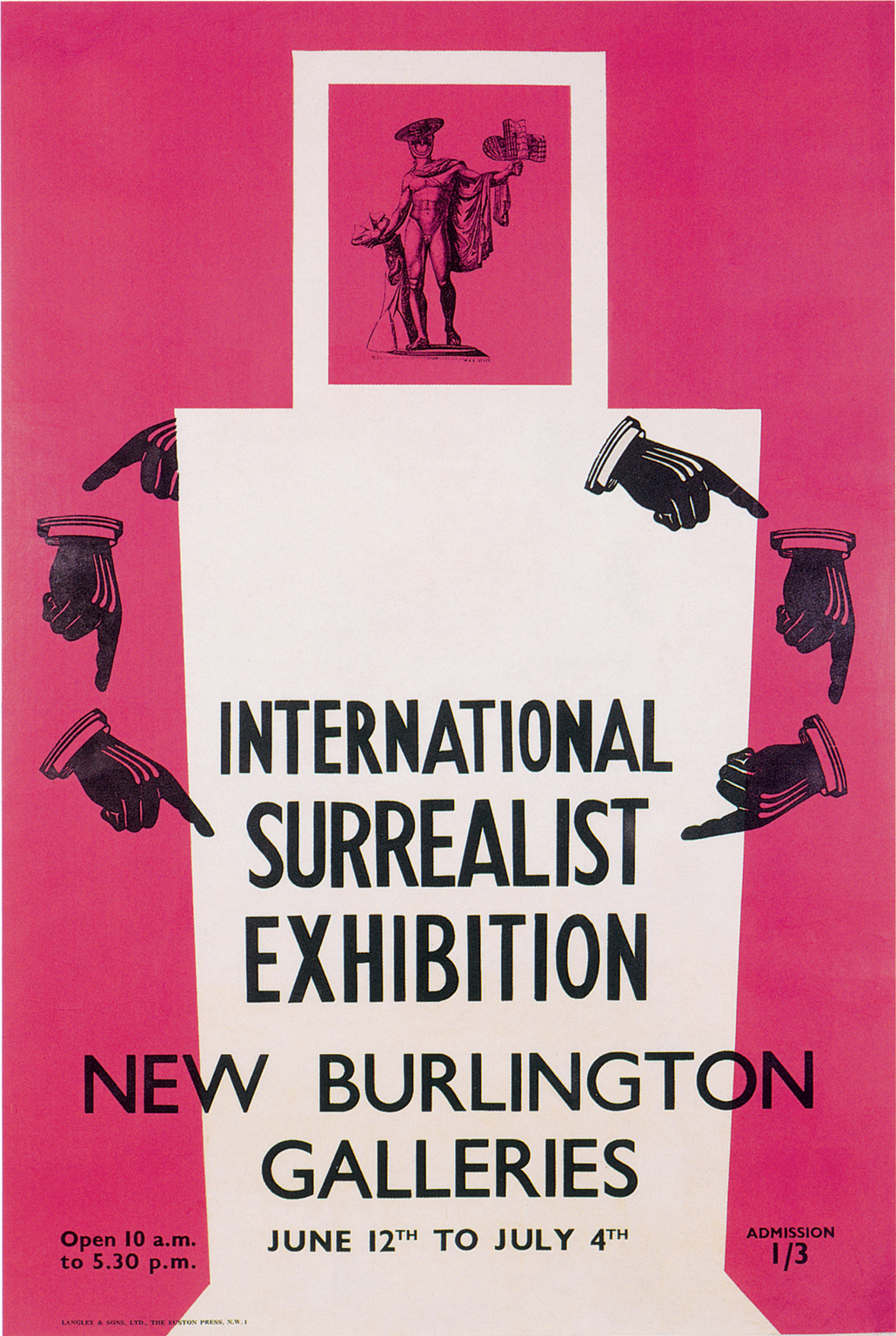

Max Ernst, poster for the International Surrealist Exhibition, New Burlington Galleries, London, 1936.

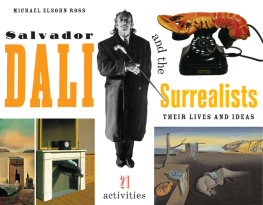

About the author

DESMOND MORRIS is one of the last surviving Surrealists. His first solo exhibition was held in 1948 and in 1950 he shared his first London show with Joan Mir. He has since completed over two and a half thousand Surrealist paintings, and eight books have been published about his work. He has also written several books, one of which (The Naked Ape, 1967) ranks among the top 100 bestsellers of all time, with over 12 million copies sold. Between 1956 and 1998 he presented a total of nearly 700 television programmes and gave over 400 television interviews.

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include:

Significant Others: Creativity and Intimate Partnership

The Lives of Lee Miller

Lives of the Great Modern Artists

The Duchamp Dictionary

CONTENTS

Surrealist artists in Paris (from left: Tristan Tzara, Paul Eluard, Andr Breton, Jean Arp, Salvador Dal, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, Ren Crevel, Man Ray), 1933. Photo by Anna Riwkin.

This book is a personal view of the surrealists, focusing on their lives rather than their work. I have restricted myself to the visual artists and have chosen the thirty-two individuals that I find most interesting. The artists are each presented in the form of a short biography, summing up their life story and discussing their personality.

The surrealist movement began in Paris in the 1920s and continued vigorously throughout the 1930s. When World War II broke out in 1939 the surrealist artists scattered, many of them ending up as refugees in New York. There, they continued to work, but when the war ended in 1945 and they returned to Paris, they found it difficult to re-activate the movement and, as an organized body, it went into a rapid decline. Most of the major artists abandoned city life at this point and went off to work elsewhere. They did not stop creating important surrealist works of art, but did so now as separate, independent individuals.

I have illustrated each of the thirty-two surrealists with a portrait photograph to show their appearance and with a typical example of their work. The portrait photos have been selected to show them as they were during the heyday of the movement and, wherever possible, I have avoided the more familiar photographs of them as mature artists. In choosing the thirty-two works of art my primary focus was on works done before the end of World War II in other words, on paintings and sculptures made during the height of the movement.

A number of authors have divided surrealist works of art into two main categories, variously called figurative and abstract, illusionistic and automatist, oneiric and free-form, or veristic and absolute. I feel that these dichotomies are too sweeping and that there are, in fact, five basic types of surrealism:

1. Paradoxical surrealism. The artist presents compositions in which the individual elements are realistically portrayed, but are irrationally juxtaposed. Example: Ren Magritte

2. Atmospheric surrealism. The artist presents a realistic composition, but with such a strange intensity that the scenes portrayed take on a dreamlike quality. Example: Paul Delvaux

3. Metamorphic surrealism. The artist portrays recognizable images but their shapes, colours and other details are distorted. The figures depicted are metamorphosing but it is still possible to recognize their original source. In their most extreme form they become little more than surrealist hieroglyphs. Example: Joan Mir

4. Biomorphic surrealism. The artist invents new figures that cannot be traced to specific, original sources, but which have an organic authenticity of their own. Example: Yves Tanguy

5. Abstract surrealism. The artist employs organic abstract shapes, but with sufficient differentiation to make them more than simply a visual pattern. Example: Arshile Gorky

Two important points need to be made about these five categories. First, many surrealists employed more than one of these approaches during their careers. Max Ernst was probably the most versatile, having used all of them at one time or another. Others, like Magritte, remained faithful to a single category. Second, the use of one of these categories is no guarantee of a successful artwork. Many people have adopted these surrealist procedures without achieving interesting results. The great mystery of surrealism and, indeed, of all art, is what makes one example of a particular genre more rewarding than another.

There has been a great deal of argument about who is a true surrealist and who is not. The purist will say that only a member of Andr Bretons inner circle can be called one. Others will say that any painting that is strange can be called surreal. I reject both extreme views. My compromise accepts the following categories:

1. Official surrealist artists

Artists who not only produced exclusively surrealist works of art but also participated in surrealist group meetings and followed the rules laid down by Breton in the surrealist manifestos. These artists agreed to operate as part of a collective, acting subversively to undermine the establishment and traditional values. They each had a vote when formally admitting or expelling someone from the group.

2. Temporary surrealists

Artists who worked in other genres but who, when they came into contact with the surrealists, entered into a surrealist phase in their work.

3. Independent surrealists

Artists who knew about the surrealists and their theories, but were individualists and not interested in any form of group activity. They were not opposed to the group, or the official aims of the movement, but as loners simply wanted no part of it.

Next page