THE PENGUIN HISTORY OF BRITAIN

General Editor David Cannadine

The Struggle for Mastery

THE PENGUIN HISTORY OF BRITAIN

I: DAVID MATTINGLY Roman Britain: 100409

II: ROBIN FLEMING Anglo-Saxon Britain: 4101066

III: DAVID CARPENTER The Struggle for Mastery: Britain 10661284

IV: MIRIAM RUBIN Britain 12721485

V: SUSAN BRIGDEN New Worlds, Lost Worlds: Britain 14851603

VI: MARK KISHLANSKY A Monarchy Transformed: Britain 16031714

VII: LINDA COLLEY A Wealth of Nations? Britain 17071815

VIII: DAVID CANNADINE The Contradictions of Progress: Britain 18001906

IX: PETER CLARKE Hope and Glory: Britain 19011989

DAVID CARPENTER

The Struggle for Mastery

BRITAIN 10661284

ALLEN LANE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

ALLEN LANE

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11, Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 2003

1

Copyright David Carpenter, 2003

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright

reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any

means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise),

without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner

and the above publisher of this book

ISBN: 978-0-14-193514-0

Contents

List of Maps and Genealogical Tables

MAPS

(pp. xiiixxi)

The counties of England

The regions of Scotland and northern England

The structure of the early Scottish state

Royal Scotland: expansion and administrative change

The regions and political divisions of Wales

Wales by c. 1200: the ebb and flow of Anglo-Norman power

The Edwardian settlement of Wales, 127795

The English expansion in Ireland

The continental possessions of the English kings after 1066

GENEALOGICAL TABLES

(pp. 53140)

The rulers of England: the English line

The rulers of England: the Norman line

The rulers of England: the Angevin line

The rulers of Scotland

The dynasty of Gwynedd

The dynasty of Deheubarth

The dynasty of Powys

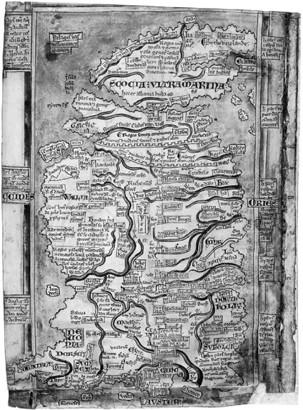

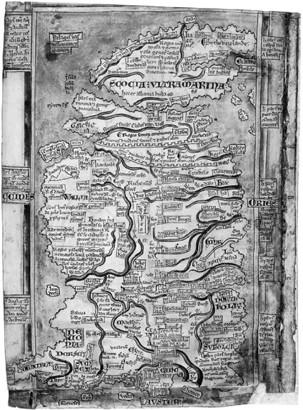

A mid-thirteenth-century map of Great Britain by Matthew Paris (British Library)

Preface

From the Norman Conquest of England to the English Conquest of Wales is the narrative span covered by this book. The one began with Duke William of Normandys landing in 1066, the other concluded with Edward Is Statute in 1284 which laid down the future government of Wales. At first sight it seems a very Anglo-centric period. The Normans master England and gradually become English. The English then master Wales before proceeding, at the end of the thirteenth century, very nearly to master Scotland as well. But this is only part of the story. After 1066 English monarchs gave far higher priority to their continental lands than they did to the intensification of their overlordship over Britain. This left plenty of space for the ambitions of the kings of Scotland and the Welsh rulers. The Struggle for Mastery in the books title is the struggle not for a single mastery of Britain but for different masteries within it. The kings of Scotland aspired to bring much of northern England into their realm and for a while managed to do so. In other directions they expanded their power more permanently, thus creating the territorial extent of modern Scotland. The Welsh rulers strove both to recover areas lost to Norman conquerors, and assert dominion over one another. The princes of Gwynedd in the thirteenth century fashioned a principality of Wales in which they subjected all the native rulers to their authority. It was only in the last quarter of the thirteenth century that these separate masteries were swept away and replaced briefly by a single English mastery of Britain.

The book begins with two thematic chapters about the peoples and economies of Britain, the former dealing with questions of national identity. There are also two later thematic chapters, one about society, and the other about the church and religion. Between and around these chapters, the spine of the book is provided by a political and governmental narrative, beginning with chapter 3. Some readers attracted by the story may prefer to begin there. The narrative offered is very much British in its form. Wales and Scotland appear for their own sake, not just when relevant to England. Sometimes their histories are treated in separate chapters, notably chapters 3 and 16, and sometimes integrated within chapters which also deal with the affairs of England. The plan throughout, rather than dividing the book into long separate sections about England, Scotland and Wales, has been to interlink their histories, showing how they were connected and how they moved together. The book also covers the English intervention in Ireland in the 1170s, and the interaction thereafter of English and Irish politics. Within the chapters which also deal with English affairs, asterisks show where sections on Wales, Scotland and Ireland begin. Asterisks are also used to indicate changes of subject matter within sections on England. Readers wishing to pursue separate themes will be able to do so with the help of the index.

British history in this period was the reverse of being self-contained. This book also reflects on how its course was influenced in new and fundamental ways by continental connections and developments, the theme of R. W. Southerns classic essay Englands first entry into Europe. England, Scotland and Wales were all, in varying degrees, affected by the papal government of the church, the new international religious orders, the learning of the European Schools, the business of the crusade, and the castles, cavalry and chivalry of the Frankish nobility. Britain was also linked to the continent as never before by the way the ruling dynasty in England down to 1204 also ruled Normandy and after 1154 Anjou and Acquitaine as well. One consequence in England was the development of uniquely powerful institutions of government to keep the peace in the kings absence and raise money to support his continental policies, a system which itself created an equally unique critique of that government, culminating in Magna Carta. If there is a watershed in British history during this period it was also provided by a continental event, the English kings loss of Normandy and Anjou in 1204, which for the first time since 1066 confined him largely to England. As a consequence, he was able to devote far more time than before to the matter of Britain. The eventual conquest of Wales later in the thirteenth century was the result.

The book is based partly on my own reading of the primary sources and partly on the secondary literature. The amount of work produced by historians in recent years has been truly remarkable. It has invigorated the old history of the period, the history of politics and the constitution, law and government, church and state, about which scholars have written since the days of Stubbs and Maitland in the nineteenth century. It has also opened up a series of new histories, examining the theory and practice of queenship, the position of women, the commercialization of the economy, the predicament of the Jews (expelled from England in 1290), the standard of living of the peasantry, the emergence of the gentry, the changing structures of magnate power, the transition from memory to written record, the nature of national identity and the relations between England and the rest of Britain. The work of historians underlies what is said on every page. Because my debt is so large, to have recorded it in detail would have made an already long book impossibly longer. In the Bibliography I have, therefore, given a broad indication of the primary sources and then made suggestions for further reading. A full account of the secondary sources will be found under my name on the Kings College London History Departments web site: www.kcl.ac.uk/history.

Next page